Scorsese’s silence

Martin Scorsese uses silence very effectively in his films. Tony Zhou explains:

(via dot info)

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

Martin Scorsese uses silence very effectively in his films. Tony Zhou explains:

(via dot info)

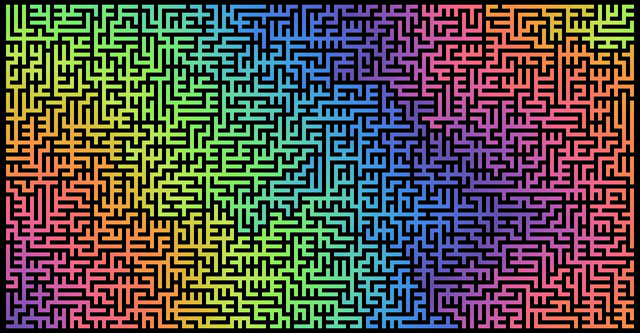

In an adaptation of a talk he gave at the recent Eyeo Festival, Mike Bostock talks about visualizing algorithms.

Algorithms are a fascinating use case for visualization. To visualize an algorithm, we don’t merely fit data to a chart; there is no primary dataset. Instead there are logical rules that describe behavior. This may be why algorithm visualizations are so unusual, as designers experiment with novel forms to better communicate. This is reason enough to study them.

But algorithms are also a reminder that visualization is more than a tool for finding patterns in data. Visualization leverages the human visual system to augment human intellect: we can use it to better understand these important abstract processes, and perhaps other things, too.

If nothing else, skim through the text and play the visualizations. The one of the maze turning into a tree visualization baked my noodle a little bit.

This terrifying machine, called a DAH Forestry Mulcher, eats an entire 30-foot tall tree in less than 15 seconds.

Ok humanity, now invent a machine that plants 30-foot tall trees in 15 seconds… (via digg)

Alan Taylor has concluded his 10-part series on WWI over at In Focus with a look at the present-day effects of the war. If you haven’t been following along, it’s worth starting at the beginning and working your way through.

Also worth a look is the NY Times’ interactive package about the war.

Clever little short film. Meta. Inappropriate.

I enjoyed this conversation about the film. I have no idea which three edits Adam thought were late, but then again I am not a fancypants filmmaker. (via @gruber)

Apple is stopping development of Aperture and iPhoto in favor of its new Photos app.

“With the introduction of the new Photos app and iCloud Photo Library, enabling you to safely store all of your photos in iCloud and access them from anywhere, there will be no new development of Aperture,” said Apple in a statement provided to The Loop. “When Photos for OS X ships next year, users will be able to migrate their existing Aperture libraries to Photos for OS.”

I wonder if the Photos app will be geared at all towards semi-pro/pro photographers or if they’ve permanently ceded that market to Lightroom.

Nice episode of 99% Invisible on how New York City got rid of the graffiti on all of their subway trains.

For decades, authorities treated subway graffiti like it was a sanitation issue. Gunn believed that graffiti was a symptom of larger systemic problems. After all, trains were derailing nearly every two weeks. In 1981 there were 1,800 subway car fires — that’s nearly five a day, every day of the year!

When Gunn launched his “Clean Trains” program, it was not only about cleaning up the trains aesthetically, but making them function well, too. Clean trains, Gunn believed, would be a symbol of a rehabilitated transit system.

Remember, the train cars used to look like this:

Television is in the midst of a protracted golden age. Anthropogenic climate change is beginning to affect the planet’s weather. Sarah Miller puts these two ideas together in a short piece of humor writing.

About half an hour later, a Boston Whaler was cruising down Ninth Avenue, and a man stood on the bow with a megaphone, shouting, “Please leave your buildings. Make your way to the nearest rooftop” in English, then in Spanish, then in Chinese. By this point, the water had risen to the top of the first floor. An emergency siren came on and stayed on. Irritated, Marci turned on the closed captioning. Then she wrote a short post about how watching “House of Cards” with subtitles revealed that, in domestic situations, people with less power spoke more words than those with more power but, in professional situations, it was the reverse. She posted it to her Tumblr. “This is so exactly what I was thinking about right now,” someone commented.

There haven’t been many good books written about soccer, but here are eleven of them worth your time. Franklin Foer’s How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization looks especially interesting.

A groundbreaking work — named one of the five most influential sports books of the decade by Sports Illustrated — How Soccer Explains the World is a unique and brilliantly illuminating look at soccer, the world’s most popular sport, as a lens through which to view the pressing issues of our age, from the clash of civilizations to the global economy.

Foer is one of the contributors, alongside authors Aleksandar Hemon and Karl Ove Knausgaard, to the New Republic’s excellent World Cup coverage.

Maybe I’m the last person in the world to see these (I don’t go out on Halloween or to clubs or do anything cool really), but these Black bar censorship sunglasses are a little bit genius:

And they look way better than wearing Google Glass. You can buy a pair on Amazon for $6. Reminds me of David Friedman’s pre-pixelated clothes for reality TV shows. (via @mrgan)

Great post on the Fermi Paradox, aka if there are so many potential intelligent civilizations out there in the universe (possibly 10 quadrillion of them), why haven’t we heard from anyone?

Possibility 5) There’s only one instance of higher-intelligent life — a “superpredator” civilization (like humans are here on Earth) — who is far more advanced than everyone else and keeps it that way by exterminating any intelligent civilization once they get past a certain level. This would suck. The way it might work is that it’s an inefficient use of resources to exterminate all emerging intelligences, maybe because most die out on their own. But past a certain point, the super beings make their move — because to them, an emerging intelligent species becomes like a virus as it starts to grow and spread. This theory suggests that whoever was the first in the galaxy to reach intelligence won, and now no one else has a chance. This would explain the lack of activity out there because it would keep the number of super-intelligent civilizations to just one.

Update: If you prefer to watch engaging videos instead of reading text, here’s six minutes on the Fermi Paradox:

Nice little video essay on information theory and Claude Shannon, “the most important man you’ve probably never heard of”.

Rather than slip away gradually into death as a different person, a woman with Alzheimer’s disease decided to commit suicide while she was still herself. Planning for her death may have helped her family with their grief.

And even though Emily Bem had supported her mother’s decision, this date — the cold reality of it — was very hard to accept.

“I said she seemed too well and it seemed too soon. I felt really angry. I felt they were all wrong,” Emily says.

And so to ease the process for their daughter and their friends, Sandy and Daryl announced that the Sunday before, everyone would gather to honor Sandy.

“We thought that would be a nice thing,” says Daryl Bem. “It made a lot more sense than a funeral where she wouldn’t be.”

On that Sunday, family and friends sat on the white couch in the living room to talk about Sandy’s life, much of which, according to Emily, Sandy had by that point forgotten.

“She just listened and listened and listened, and at the end she would say, ‘Wow, I did that? Amazing. Amazing!’ “

Emily says when she showed up at the meeting she was still very angry, convinced that her mother should hold on. Emily, who also lives in Ithaca, has a toddler. She wanted more time with her mother. But over the course of the meeting, this feeling began to ebb.

(via @scottlamb)

Com Truise remix of Tycho’s Awake? Yes please.

Now get Kygo to remix the remix and we’ll have the perfect kottke.org sleepy beats trifecta.

Beginning in 1991, Zed Nelson took a photo of the same family (father, mother, and son) in front of the same backdrop every year for 21 years. Here’s the first photo:

And the most recent one:

There are many more such projects, including the Goldberg family’s annual portraits, Nicholas Nixon’s annual portraits of The Brown Sisters, and Noah Kalina’s Everyday.

Watch as two players from the Japanese national soccer team try to score against 55 kids.

The kids had two opportunities to stop the pro players, once with 33 players and the second time with 55 players. This didn’t turn out how I expected, given how a similar stunt involving fencing ended.

This was posted on Marginal Revolution a few days ago and garnered several interesting comments about how much better professional athletes are than us regular folk. Here are a few:

Rugby: I played against an international player once. Watching him play, I’d seen a chap who ran in straight lines, a strong tackler with a weak kick. Playing against him revealed him to be skillful, agile and possessed of a howitzer kick.

Back in the 1980s a friend was watching a pickup basketball game in Boston and reported what happened when a player from the Celtics showed up. He was so much faster, more athletic, and more agile than the other players that it seemed like he was playing a different sport. The player turned out to be Scott Wedman, who by that time was old and slow by NBA standards, and mainly hung around the 3-point line to shoot outside shots after the defense had collapsed on Bird, McHale, et al. But compared to non-NBA players, he was Michael Jordan (or LeBron James).

My U-19 team (we were very good by local standards) had a practice with the New Zealand All Blacks, who were on some sort of tour. It was like they were from a different planet. I stood no chance of containing, or conversely getting past, the smallest of them under almost any circumstance.

Back in the olden thymes I was a pretty good baseball player. Early in my high school career I got the chance to catch a AAA pitcher. I went into thinking I would have no trouble. The first pitch was on top of me so fast I was knocked off balance. It took a bunch of pass balls before I got used to how to handle his breaking stuff.

The result in the video might also shed some light on the question of choosing to fight one horse-sized duck or 100 duck-sized horses.

If you took all the fight scenes from Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill movies and turned them into a Double Dragon-esque video game, this is what it would look like:

(via devour)

Burkhard Bilger writes for the New Yorker about extreme cavers and their effort to explore what may be the deepest cave in the world.

When the call to base camp was over, Gala hiked to the edge of the pool with his partner, the British cave diver Phil Short, and they put on their scuba rebreathers, masks, and fins. They’d spent the past two days on a platform suspended above another sump, rebuilding their gear. Many of the parts had been cracked or contaminated on the way down, so the two men took their time, cleaning each piece and cannibalizing components from an extra kit, knowing that they’d soon have no time to spare. The water here was between fifty and sixty degrees — cold enough to chill you within minutes — and Gala had no idea where the pool would lead. It might offer swift passage to the next shaft or lead into an endless, mud-dimmed labyrinth.

The rebreathers were good for four hours underwater, longer in a pinch. They removed carbon dioxide from a diver’s breath by passing it through cannisters of soda lime, then recirculating it back to the mouthpiece with a fresh puff of oxygen. Gala and Short were expert at managing dive time, but in the background another clock was always ticking. The team had arrived in February, three months before the rainy season. It was only mid-March now, but the weather wasn’t always predictable. In 2009, a flash flood had trapped two of Gala’s teammates in these tunnels for five days, unsure if the water would ever recede.

Gala had seen traces of its passage on the way down: old ropes shredded to fibre, phone lines stripped of insulation. When the heavy rain began to fall, it would flood this cave completely, trickling down from all over the mountain, gathering in ever-widening branches, dislodging boulders and carving new tunnels till it poured from the mountain into the Santo Domingo River. “You don’t want to be there when that happens,” Stone said. “There is no rescue, period.” To climb straight back to the surface, without stopping to rig ropes and phone wire, would take them four days. It took three days to get back from the moon.

Bilger writes about this sort of thing so well…glad I didn’t miss this one.

I missed this news a couple of months ago: Steven Spielberg is going to direct a movie version of Roald Dahl’s The BFG.

Renowned film director Steven Spielberg will direct the new adaptation with Melissa Mathison, who last worked with Spielberg on ET, writing the script. Frank Marshall will produce the film and Michael Siegel and John Madden are on board as executive producers.

I can’t find any direct evidence, but the way the news is being reported, this seems like it’ll be a live-action film and not a Tintin 3-D motion capture affair.

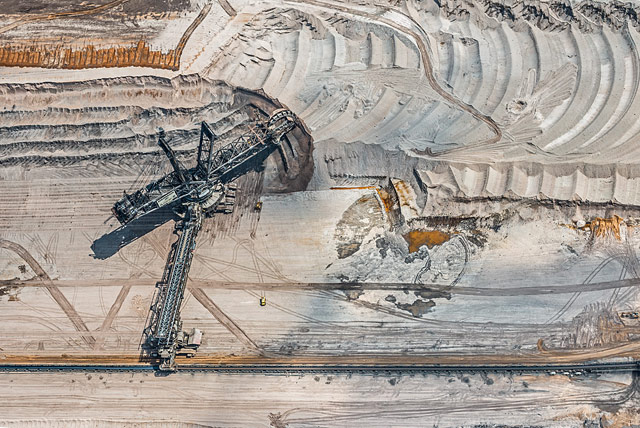

From Bernhard Lang, aerial photos of the largest made-made hole in Europe, the Hambach Mine in Germany. The mine was started in 1978, is 1150 feet deep, and will eventually encompass an area of over 32 square miles. Here’s the mine on Google Maps; it’s huge.

That’s a photo of one of the massive mining machines used to extract lignite (aka “brown coal”) from the mine. The machines are almost 800 feet long and 315 feet high…those yellow specks to the right of the machine are likely fairly sizable construction trucks. (via co.exist)

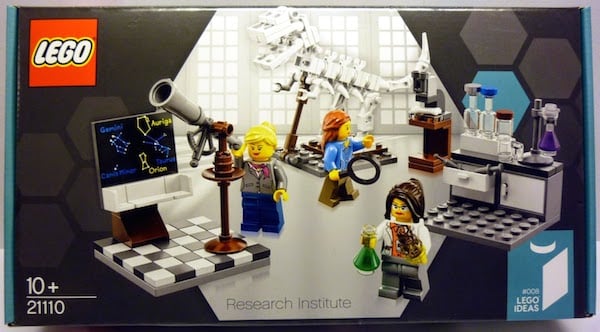

2014 is the first year without a Pixar film since 2005’s gap between The Incredibles and Cars. The company has two films planned for 2015 and one of them will hopefully do something about one of my long-standing pet peeves about their movies: the lack of strong women characters. Inside Out takes place inside the brain of a teenaged girl, with her emotions as the main characters.

The film’s real protagonist is Joy (voiced by an effervescent Amy Poehler), one of five emotions who steer Riley through life via a control center in her mind that’s akin to the bridge from the Starship Enterprise. Joy and her cohorts — including Fear (Bill Hader), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), Anger (Lewis Black), and Sadness (Phyllis Smith) — all work together to keep Riley emotionally balanced, and for the first 11 years of her life, the primary influencer is Joy, as evidenced by Riley’s sunny demeanor.

But as adolescence sets in, Joy finds her lead role usurped. Suddenly, Sadness wants to pipe in at inappropriate times — coaxing Riley to cry during her first day at a new school, for instance — and as the two emotions jostle for control, both of them fall into the deepest reaches of Riley’s mind and have to work their way back. Meanwhile, left to their own devices, Fear, Disgust, and Anger collude to transform Riley into a moody preteen.

Holy cow, that sounds great.

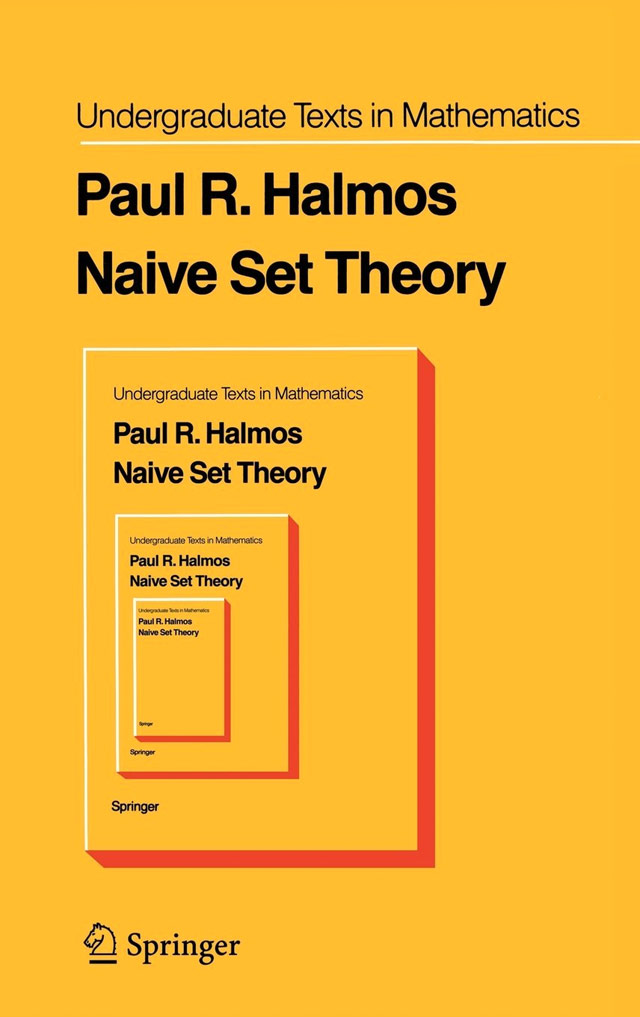

The book cover for Naive Set Theory by Paul Halmos is so so good:

The cover is a riff on, I think, Russell’s Paradox, a problem with naive set theory described by Bertrand Russell in 1901 about whether sets can contain themselves.

Russell’s paradox is based on examples like this: Consider a group of barbers who shave only those men who do not shave themselves. Suppose there is a barber in this collection who does not shave himself; then by the definition of the collection, he must shave himself. But no barber in the collection can shave himself. (If so, he would be a man who does shave men who shave themselves.)

Reminds me of David Pearson’s genius cover for Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

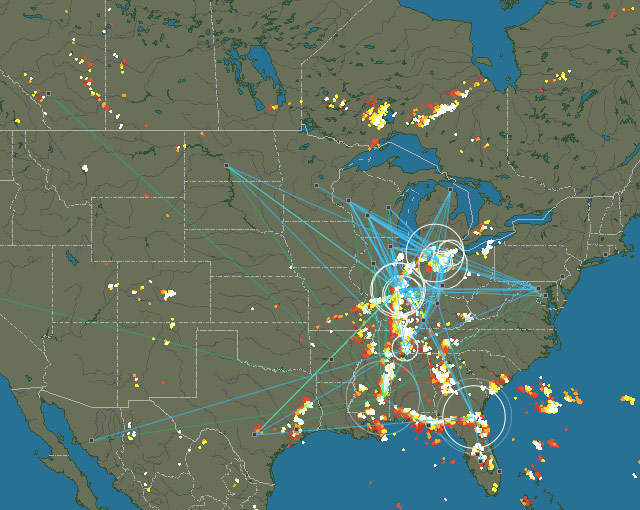

This map showing where lighting strikes are happening right now is kind of great:

Average delay is about 3-5 seconds. Make sure you turn the sound up too. That’s the North American map…there are also maps for Europe, Asia, Australia, and South America, although only NA, Europe, and Australia seem to have detectors in place.

The detection system is volunteer community effort. Anyone who wants to can buy a detection kit (for around 200 Euro) and hook it up to the Internet to provide strike data. In turn, the data collected from stations is made available to any station owner. See also the wind map of the Earth and the realtime map of global ocean currents.

Paul Greenberg has an excerpt in the NY Times of his new book, American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood.

As go scallops, so goes the nation. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, even though the United States controls more ocean than any other country, 86 percent of the seafood we consume is imported.

But it’s much fishier than that: While a majority of the seafood Americans eat is foreign, a third of what Americans catch is sold to foreigners.

The seafood industry, it turns out, is a great example of the swaps, delete-and-replace maneuvers and other mechanisms that define so much of the outsourced American economy; you can find similar, seemingly inefficient phenomena in everything from textiles to technology. The difference with seafood, though, is that we’re talking about the destruction and outsourcing of the very ecological infrastructure that underpins the health of our coasts.

The article and book focus on three formerly American seafoods that we now mostly import from elsewhere: salmon, oysters, and shrimp.

In 2005, the United States imported five billion pounds of seafood, nearly double what we imported twenty years earlier. Bizarrely, during that same period, our seafood exports quadrupled. American Catch examines New York oysters, Gulf shrimp, and Alaskan salmon to reveal how it came to be that 91 percent of the seafood Americans eat is foreign.

In the 1920s, the average New Yorker ate six hundred local oysters a year. Today, the only edible oysters lie outside city limits. Following the trail of environmental desecration, Greenberg comes to view the New York City oyster as a reminder of what is lost when local waters are not valued as a food source.

Farther south, a different catastrophe threatens another seafood-rich environment. When Greenberg visits the Gulf of Mexico, he arrives expecting to learn of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s lingering effects on shrimpers, but instead finds that the more immediate threat to business comes from overseas. Asian-farmed shrimp-cheap, abundant, and a perfect vehicle for the frying and sauces Americans love-have flooded the American market.

Finally, Greenberg visits Bristol Bay, Alaska, home to the biggest wild sockeye salmon run left in the world. A pristine, productive fishery, Bristol Bay is now at great risk: The proposed Pebble Mine project could undermine the very spawning grounds that make this great run possible. In his search to discover why this precious renewable resource isn’t better protected, Greenberg encounters a shocking truth: the great majority of Alaskan salmon is sent out of the country, much of it to Asia. Sockeye salmon is one of the most nutritionally dense animal proteins on the planet, yet Americans are shipping it abroad.

This is intense: video from one of the riders during the sprint finish of stage 5 of the Tour de Suisse.

I don’t know how all of those riders are working that hard so close together without constantly crashing into each other. The number of “I’ve got my bike slightly in front of your bike now move the hell over” moves shown in the video reminded me of how NYC taxi drivers negotiate the streets of Manhattan. (via @polarben)

For a Visa commercial, Errol Morris gathers a number of Nobel Peace Prize winners and nominees (including Lech Walesa) to talk about how important it is for their countries to beat the crap out of the other countries in the World Cup.

Two quotes in the video caught my ear:

Sport is a continuation of war by other means.

Look, football isn’t life or death. It’s much more important than that.

The first is a riff on Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz’s aphorism “War is the continuation of Politik by other means”. Clausewitz also devised the concept of “the fog of war”, which Morris used for the title of a film. The second is a paraphrase of a quote by legendary football coach Bill Shankly:

Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.

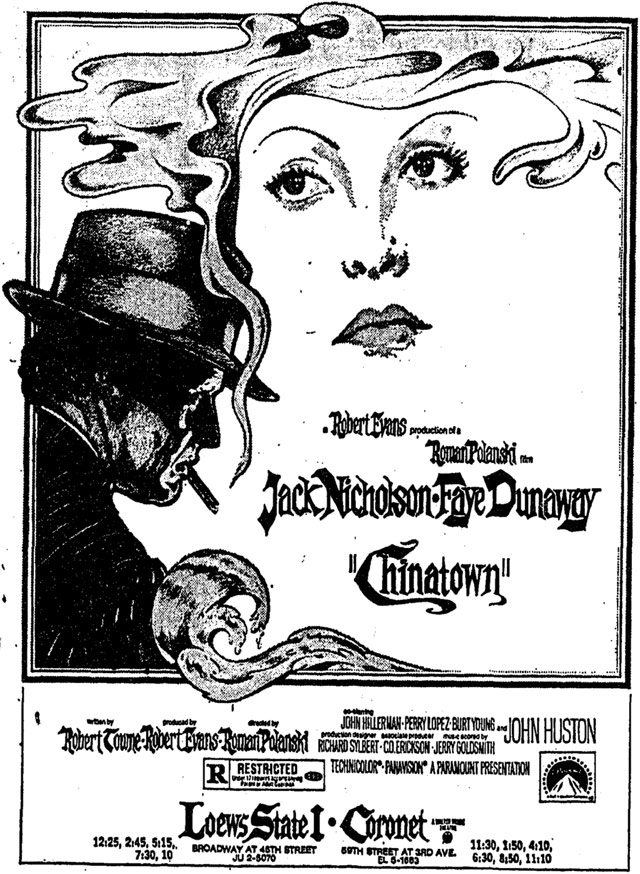

Yesterday, I did a round-up of movies, TV, and music available on this weekend in 1984. As a comparison, I thought looking at the same weekend from 1974 would be interesting. Tracking this information down was a little more difficult than with 1984, but I found most of what I needed in the June 23, 1974 edition of the NY Times.

Back in the 1970s (and probably particularly in NYC), movies stayed in theaters a lot longer than they do now. There was no home video market then…you either saw the movie in the theater or you missed it. This is a list of some of the movies available for viewing in theaters that weekend in NYC:

The Sting

The Exorcist

Parallax View

The Sugarland Express

The Conversation

Chinatown

Papillon

The Great Gatsby

The Sting, Papillon, and The Exorcist had been out since late 1973, The Great Gatsby since March, and The Sugarland Express (Spielberg’s directoral debut) and The Conversation since April. Only Parallax View and Chinatown had just opened. Interestingly, the year’s top-grossing film, Blazing Saddles, which opened in February, didn’t appear anywhere on the movie listing pages of the Times that week.

The top 10 on the Billboard chart for that week were:

Billy, Don’t Be A Hero - Bo Donaldson And The Heywoods

You Make Me Feel Brand New - The Stylistics

Sundown - Gordon Lightfoot

The Streak - Ray Stevens

Be Thankful For What You Got - William DeVaughn

Band On The Run - Paul McCartney & Wings

If You Love Me (let Me Know) - Olivia Newton-John

Dancing Machine - Jackson 5

Hollywood Swinging - Kool & The Gang

The Entertainer - Marvin Hamlisch/The Sting

And on TV that weekend, a number of classic shows, all reruns except for 60 Minutes:

Brady Bunch

Sanford and Son

Good Times

Upstairs, Downstairs

The Odd Couple

All in the Family

M*A*S*H

Mary Tyler Moore

60 Minutes

BTW, the entire copy of the Sunday Times was fascinating to page through. The ads for cigarettes, hand-held calculators, and color televisions, real estate listings, job openings, book listings, the NY Times Magazine, car ads, etc.

On this weekend 30 years ago, in the summer of 1984, you could stroll into a movie theater and choose between the following films:

Ghostbusters

Gremlins

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

The Karate Kid

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

Top Secret!

The Natural

Police Academy

Plus, Sixteen Candles and Footloose had just closed the weekend before. 1984 was generally a great year for movies. Musically, the following songs were in heavy rotation on the radio and on MTV that weekend:

The Reflex - Duran Duran

Time After Time - Cyndi Lauper

Let’s Hear It for the Boy - Deniece Williams

Dancing in the Dark - Bruce Springsteen

Self Control - Laura Branigan

The Heart of Rock & Roll - Huey Lewis

Jump - The Pointer Sisters

When Doves Cry - Prince

Eyes Without a Face - Billy Idol

Borderline - Madonna

On TV that weekend were mostly reruns and movies…networks only showed reruns in the summer back then. The shows airing included:

The Dukes of Hazzard

Fantasy Island

Webster

Dallas

Diff’rent Strokes

60 Minutes

The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson

Late Night with David Letterman

(via, no foolin’, the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man)

Aatish Bhatia noticed a plant in his backyard whose leaves naturally repelled water. He took a sample to a friend who had access to a high-speed camera and an electron microscope to investigate what made the leaves so hydrophobic.

But how does a leaf become superhydrophobic? The trick to this, Janine explained, is that the water isn’t really sitting on the surface. A superhydrophobic surface is a little like a bed of nails. The nails touch the water, but there are gaps in between them. So there’s fewer points of contact, which means the surface can’t tug on the water as much, and so the drop stays round.

The leaf is so water repellant that drops of water bounce right off of it:

Rian Johnson, director of Brick and Looper (both of which I really enjoyed) and one of the best episodes of Breaking Bad, is rumored to be the director of the 8th and 9th episodes of Star Wars.

Johnson will take over the core film franchise, and he’ll get started quickly and this will be his preoccupation for quite awhile. Technically, he’ll write that second treatment but the intention on both sides is that he direct the two installments.

First Abrams and now this…Disney seems to be doing a much better job shepherding the Star Wars franchise than Lucas did. (via df)

David Auerbach writes about the high you get from coding.

These days I write more than I code, but one of the things I miss about programming is the coder’s high: those times when, for hours on end, I would lock my vision straight at the computer screen, trance out, and become a human-machine hybrid zipping through the virtual architecture that my co-workers and I were building. Hunger, thirst, sleepiness, and even pain all faded away while I was staring at the screen, thinking and typing, until I’d reach the point of exhaustion and it would come crashing down on me.

It was good for me, too. Coding had a smoothing, calming effect on my psyche, what I imagine meditation does to you if you master it.

Auerbach asserts that there’s something different about the flow state one enters while programming, compared to those brought on by making art, writing, etc. Over the years, I’ve written, designed, and programmed for a living, and programming is, by far, the thing that gets me the best high. I’ve definitely had productive multi-hour Photoshop and writing benders, but coding blocks out the world and the rest of myself like nothing else. In attempting to articulate to friends why I enjoy programming more than design or writing, I’ve been explaining it like this: for me, the coding process is all or nothing and has a definitive end.

When code doesn’t work within the specifications, it’s 100% broken. It won’t compile, the web server throws an error, or gives the wrong output. Writing and design almost always sorta work…even a first draft or an initial design communicates something to the reader/viewer. When the code works within the specifications, it’s done. The writing or design process is never done; even a great piece of writing or the best design can be improved incrementally or even scrapped altogether to go in a different and potentially more fruitful direction. Maybe, for me, programming’s definite ending is what makes it so enjoyable. The flow state comes from knowing that, while the journey is difficult and maddening and messily creative (just as with writing or design), there’s a definite point at which it’s done and you can move on to the next challenge. (via 5 intriguing things)

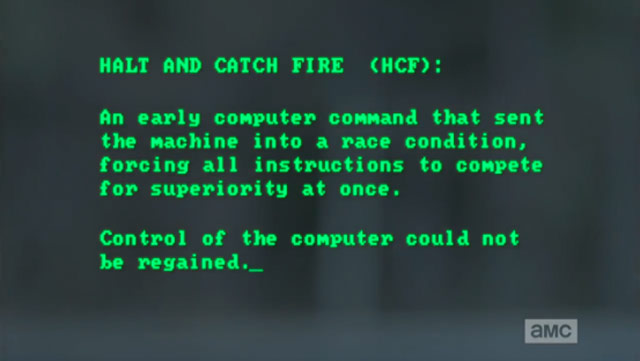

I’ve been hearing some good things about Halt and Catch Fire, which is three episodes into its first season on AMC. The show follows a group of 80s computer folk as they attempt to reverse engineer the IBM PC. The first episode is available online in its entirety.

Many reviews mention the similarity of the characters to Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, but the trio of managers from Texas Instruments who left to form Compaq in the early 80s are a much closer fit. The Compaq Portable was the first 100% IBM compatible computer produced. Brian McCullough recently did a piece on Compaq’s cloning of the IBM PC for the Internet History Podcast.

The idea was to create a computer that was mostly like IBM-PC and mostly ran all the same software, but sold at a cheaper price point. The first company to pursue this strategy was Columbia Data Products, followed by Eagle Computer. But soon, most of the big names in the young computer industry (Xerox, Hewlett-Packard, Digital Equipment Corporation, Texas Instruments, and Wang) were all producing PC clones.

But all of these machines were only mostly PC-compatible. So, at best, they were DOS compatible. But there was no guarantee that each and every program or peripheral that ran on the IBM-PC could run on a clone. The key innovation that Canion, Harris and Murto planned to bring to market under the name Compaq Computer Corporation would be a no-compromises, 100% IBM-PC compatibility. This way, their portable computer would be able to run every single piece of software developed for the IBM-PC. They would be able to launch their machine into the largest and most vibrant software ecosystem of the time, and users would be able to use all their favorite programs on the road.

My dad bought a machine from Columbia Data Products; I had no idea it was the first compatible to the market. My uncle had a Compaq Portable that he could take with him on business trips. I played so much Lode Runner on both of those machines. I wonder if that disk of levels I created is still around anywhere… (via @cabel)

Update: I’m all caught up, five episodes into the season, and I’m loving it.

NYC and the Central Park Five have agreed to a $40 million settlement that will bring a years-long civil rights lawsuit to an end.

The five men whose convictions in the brutal 1989 beating and rape of a female jogger in Central Park were later overturned have agreed to a settlement of about $40 million from New York City to resolve a bitterly fought civil rights lawsuit over their arrests and imprisonment in the sensational crime.

The agreement, reached between the city’s Law Department and the five plaintiffs, would bring to an end an extraordinary legal battle over a crime that came to symbolize a sense of lawlessness in New York, amid reports of “wilding” youths and a marauding “wolf pack” that set its sights on a 28-year-old investment banker who ran in the park many evenings after work.

Ken Burns made a documentary film about this case in 2012. Highly recommended viewing…and you can watch the whole thing on the PBS web site.

In the New Yorker, Michael Specter writes generally about the malleability of memory and specifically about Daniela Schiller’s research on disassociating people’s memories from the feelings they have about them. Simply recalling a memory can change it, and Schiller has found evidence that process can be used to remove the feelings of stress, anxiety, and fear associated with certain memories.

Even so, Schiller entered her field at a fortunate moment. After decades of struggle, scientists had begun to tease out the complex molecular interactions that permit us to form, store, and recall many different types of memories. In 2004, the year Schiller received her doctorate in cognitive neuroscience, from Tel Aviv University, she was awarded a Fulbright fellowship and joined the laboratory of Elizabeth Phelps, at New York University. Phelps and her colleague Joseph LeDoux are among the nation’s leading investigators of the neural systems involved in learning, emotion, and memory. By coincidence, that was also the year that the film “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” was released; it explores what happens when two people choose to have all their memories of each other erased. In real life, it’s not possible to pluck a single recollection from our brains without destroying others, and Schiller has no desire to do that. She and a growing number of her colleagues have a more ambitious goal: to find a way to rewrite our darkest memories.

“I want to disentangle painful emotion from the memory it is associated with,” she said. “Then somebody could recall a terrible trauma, like those my father obviously endured, without the terror that makes it so disabling. You would still have the memory, but not the overwhelming fear attached to it. That would be far more exciting than anything that happens in a movie.” Before coming to New York, Schiller had heard — incorrectly, as it turned out — that the idea for “Eternal Sunshine” originated in LeDoux’s lab. It seemed like science fiction and, for the most part, it was. As many neuroscientists were aware, though, the plot also contained more than a hint of truth.

Over the course of his 3000 columns at The Motley Fool, Morgan Housel has learned a few things:

I’ve learned that short-term thinking is at the root of most of our problems, whether it’s in business, politics, investing, or work.

I’ve learned that debt can cause more social problems than some drugs, yet drugs are illegal and debt is tax deductible.

I’ve learned that finance is actually very simple, but it’s made to look complicated to justify fees.

Unfortunately, the list is undermined almost completely by the get-rich-quick advertising on the site, including this bit at the end of the article, which I can’t even tell is an ad or just a promotion:

Opportunities to get wealthy from a single investment don’t come around often, but they do exist, and our chief technology officer believes he’s found one. In this free report, Jeremy Phillips shares the single company that he believes could transform not only your portfolio, but your entire life. To learn the identity of this stock for free and see why Jeremy is putting more than $100,000 of his own money into it, all you have to do is click here now.

Short-term thinking is at the root of most of our problems, click here now. Now!

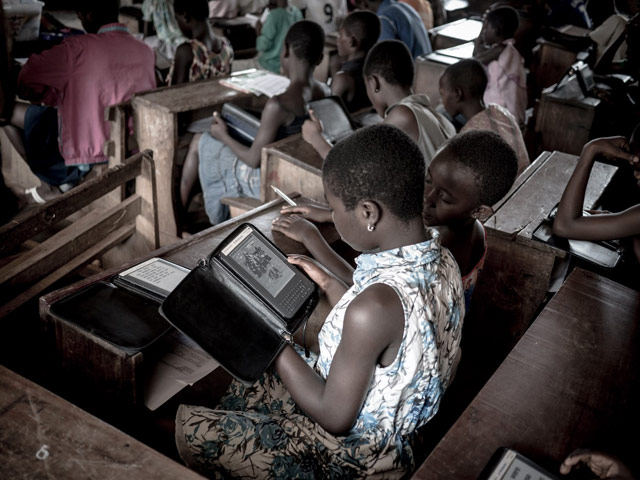

Craig Mod visited Ghana recently to check on the progress of Worldreader, an organization dedicated to distributing digital books to children and families in places like Rwanda, Ghana, and South Africa.

Those of us who work in technology tend to take religious-like stances over its ability to change the world, always for the better. My paranoia of trickery comes from an inherent suspicion towards technology, and an even deeper suspicion of presuming to know better. It’s too easy to fall into the first-world trope of “all the poor need is a little sprinkling of silicon and then everything will be fine.” It’s never that simple. Technology is, at best, the tip of the iceberg. A very tiny component of the work that needs to be done in the greater whole of reforming or impacting or increasing accessibility to education, first-world and third-world alike. Technology deployed without infrastructure, without understanding, without administrative or community support, without proper curriculum is nearly worthless. Worse than worthless, even — for it can be destructive, the time and budget spent on the technology eating into more fundamental, more meaningful points of badly needed reform.

You’ve probably seen Bruce Davidson’s photos of the gritty 1980s NYC subway, which were collected into a book published in 1986.

Earlier this year, Time posted some previously unpublished photos of the NYC subway taken in 1981 by Christopher Morris, an admirer of Davidson’s.

Tom Chiarella shares his rules for giving a eulogy.

It may hurt to write it. And reading it? For some, that’s the worst part. The world might spin a little, and everything familiar to you might fade for a few minutes. But remember, remind yourself as you stand there, you are the lucky one.

And that’s not because you aren’t dead. You were selected. You get to stand, face the group, the family, the world, and add it up. You’re being asked to do something at the very moment when nothing can be done. You get the last word in the attempt to define the outlines of a life. I don’t care what you say, bub: That is a gift.

This rule surprised me:

You must make them laugh. Laughs are a pivot point in a funeral. They are your responsibility. The best laughs come by forcing people not to idealize the dead. In order to do this, you have to be willing to tell a story, at the closing of which you draw conclusions that no one expects.

In France, pie charts are called “le camembert” after the cheese. Or sometimes “un diagramme en fromage” (cheese diagram). In Brazil, they are pizza charts. (via numberphile & reddit)

Before Adolf Hitler came along and seized the title of the most evil person in the world, who was commonly cited as the embodiment of evil? The Egyptian Pharoah in the story of Exodus.

In the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, many Americans and Europeans had a firmer grasp of the bible than of the history of genocidal dictators. Orators in search of a universal symbol for evil typically turned to figures like Judas Iscariot, Pontius Pilate, or, most frequently, the Pharaoh of Exodus, who chose to endure 10 plagues rather than let the Hebrew people go. In Common Sense, Thomas Paine wrote: “No man was a warmer wisher for reconciliation than myself, before the fatal nineteenth of April, 1775 [the date of the Lexington massacre], but the moment the event of that day was made known, I rejected the hardened, sullen tempered Pharaoh of England for ever.” In the run-up to the Civil War, abolitionists regularly referred to slaveholders as modern-day Pharaohs. Even after VE Day, Pharaoh continued to pop up in the speeches of social reformers like Martin Luther King Jr.

Also, this is a good line:

Generally speaking, hatred was more local and short-lived before World War II.

(via mr)

From Popular Mechanics, a list of survival tips covering a variety of outdoor situations, from watching a baseball game to cutting down trees to drinking too much water during exercise.

We all know that dehydration can be dangerous, leading to dizziness, seizures, and death, but drinking too much water can be just as bad. In 2002, 28-year-old runner Cynthia Lucero collapsed midway through the Boston Marathon. Rushed to a hospital, she fell into a coma and died. In the aftermath it emerged that she had drunk large amounts along the run. The excess liquid in her system induced a syndrome called exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH), in which an imbalance in the body’s sodium levels creates a dangerous swelling of the brain.

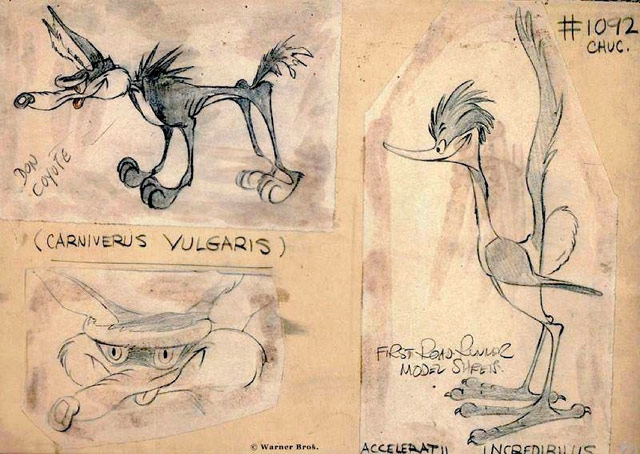

From the official Chuck Jones Tumblr, an early sketch of the Road Runner and Coyote by Jones.

Also by Jones, how to draw Bugs Bunny:

(via @peeweeherman)

Former MLB player Tony Gwynn passed away the other day. Cancer. He was only 54. Gwynn was one of my favorite players as a kid…I’ve always liked the players who hit for average and rarely struck out. Rarely got to see him play because I lived in American League country, so I knew him mainly through his statistics and baseball cards. These pieces by Jay Caspian Kang, Buster Olney, and Bob Nightengale are all worth reading to hear about Gwynn’s humanity and cerebral approach to the game, but Keith Olbermann’s heartfelt eulogy was my favorite piece in the wake of Gwynn’s death.

A new study finds that insider trading is much worse than commonly thought: a quarter of all public company deals may involve some kind of insider trading. From the NY Times:

The professors examined stock option movements — when an investor buys an option to acquire a stock in the future at a set price — as a way of determining whether unusual activity took place in the 30 days before a deal’s announcement.

The results are persuasive and disturbing, suggesting that law enforcement is woefully behind — or perhaps is so overwhelmed that it simply looks for the most egregious examples of insider trading, or for prominent targets who can attract headlines.

The professors are so confident in their findings of pervasive insider trading that they determined statistically that the odds of the trading “arising out of chance” were “about three in a trillion.” (It’s easier, in other words, to hit the lottery.)

Only about 5% of the deals are ever litigated by the SEC. (via mr)

The Mozart Project is a book about the life and music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Or is it an app? Stephen Fry calls it “a completely new kind of book”…you read it in iBooks but it acts more like an app than anything. Over 200 pages of text by leading Mozart scholars is accompanied by hours of music, videos, photo slideshows, all sorts of other goodies.

Curated and authored by some of the most respected experts, The Mozart Project gives new insight into the life of a musical genius, providing the ultimate experience both in terms of contributors and the carefully selected playlist of music and images that they have chosen to feature throughout the book.

The NY Times has a bunch of photos by Seth Casteel of babies undergoing infant survival swim training.

Zoe was being introduced to “self-rescue,” in which babies are taught to hold their breath underwater, kick their feet, turn over to float on their backs and rest until help arrives.

The self-rescue idea is pretty amazing. You take kids who can’t talk and can barely walk and teach them how to float on their backs. I didn’t really believe it until I saw it:

Bonus summer PSA: drowning doesn’t look like drowning.

The center of the population of the United States has been moving steadily west and south since 1790. This video shows the progression until 2010:

You can step through the animation yourself on the US Census Bureau site. It’s interesting to see how even the changes are…there was one big jump from 1850 to 1860 and a slow down in westward migration from 1890 to 1940, but other than that, it shifted west about 40-50 miles each decade.

The black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy is estimated to have a mass of 4 million Suns. The largest black hole astronomers have found so far has a mass of 18 billion solar masses, or more than 4000 times as massive as the Milky Way’s.

Around 3.5 billion light-years away, this galaxy is estimated to contain the largest black hole presently known, at 18 billion solar masses. (Although, the error bars for this one and NGC 1277’s overlap substantially.) But the most spectacular part of this galaxy — and why we’re able to learn so much about it’s central region — is because there’s a 100 million Solar mass black hole (that’s 25 times larger than the one at the Milky Way’s core) that’s orbiting the even larger one!

Also, the largest know galaxy in the Universe is IC 1101, with a mass of 100 trillion solar masses.

It’s possible to make a .zip file that contains itself infinitely many times. So a 440 byte file could conceivably be expanded into eleventy dickety two zootayunafliptobytes of data and beyond. Here’s the full explanation.

An instant classic John Gruber post about the sort of company Apple is right now and how it compares in that regard to its four main competitors: Google, Samsung, Microsoft, and Amazon. The post is also about how Apple is now firmly a Tim Cook joint, and the company is better for it.

When Cook succeeded Jobs, the question we all asked was more or less binary: Would Apple decline without Steve Jobs? What seems to have gone largely unconsidered is whether Apple would thrive with Cook at the helm, achieving things the company wasn’t able to do under the leadership of the autocratic and mercurial Jobs.

Jobs was a great CEO for leading Apple to become big. But Cook is a great CEO for leading Apple now that it is big, to allow the company to take advantage of its size and success. Matt Drance said it, and so will I: What we saw last week at WWDC 2014 would not have happened under Steve Jobs.

This is not to say Apple is better off without Steve Jobs. But I do think it’s becoming clear that the company, today, might be better off with Tim Cook as CEO. If Jobs were still with us, his ideal role today might be that of an eminence grise, muse and partner to Jony Ive in the design of new products, and of course public presenter extraordinaire. Chairman of the board, with Cook as CEO, running the company much as he actually is today.

This bit on the commoditization of hardware, and Apple’s spectacularly successful fight against it, got me thinking about current events. Here’s Gruber again:

Apple’s device-centric approach provides them with control. There’s a long-standing and perhaps everlasting belief in the computer industry that hardware is destined for commoditization. At their cores, Microsoft and Google were founded on that belief - and they succeeded handsomely. Microsoft’s Windows empire was built atop commodity PC hardware. Google’s search empire was built atop web browsers running on any and all computers. (Google also made a huge bet on commodity hardware for their incredible back-end infrastructure. Google’s infrastructure is both massive and massively redundant - thousands and thousands of cheap hardware servers running custom software designed such that failure of individual machines is completely expected.)

This is probably the central axiom of the Church of Market Share - if hardware is destined for commoditization, then the only thing that matters is maximizing the share of devices running your OS (Microsoft) or using your online services (Google).

The entirety of Apple’s post-NeXT reunification success has been in defiance of that belief - that commoditization is inevitable, but won’t necessarily consume the entire market. It started with the iMac, and the notion that the design of computer hardware mattered. It carried through to the iPod, which faced predictions of imminent decline in the face of commodity music players all the way until it was cannibalized by the iPhone.

And here’s David Galbraith tweeting about the seemingly unrelated training that London taxi drivers receive, a comment no doubt spurred by the European taxi strikes last week, protesting Uber’s move into Europe:

Didn’t realize London taxi drivers still have to spend years learning routes. That’s just asking to be disrupted http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxicabs_of_the_United_Kingdom#The_Knowledge

Here’s the relevant bit from Wikipedia about The Knowledge:

It is the world’s most demanding training course for taxicab drivers, and applicants will usually need at least twelve ‘appearances’ (attempts at the final test), after preparation averaging 34 months, to pass the examination.

Uber, in this scenario, is attempting to be Microsoft in the 1980s and early 90s. They’re implementing their software layer (the Uber service) on commodity hardware, which includes not only iPhones & Android phones, mass-produced cars of any type, and GPS systems but also, and crucially, the drivers themselves. Uber is betting that a bunch of off-the-shelf hardware, “ordinary” drivers, and their self-service easy-pay dispatch system will provide similar (or even better) results than a fleet of taxi drivers each with three years of training and years of experience. It is unclear to me what the taxi drivers can do in this situation to emulate the Apple of 1997 in making that commoditization irrelevant to their business prospects. Although when it comes to London in particular, Uber may have miscalculated: in a recent comparison at rush hour, an Uber cab took almost three times as long and was 64% more expensive than a black cab.

Paul Ford writes about the connection between kitty litter and internet culture. In short, kitty litter led to house cats which led to cat memes.

Certainly Ed Lowe in 1947 could never have predicted the memes and clickbait that would follow, but he figured out a fundamental rule that applies today as well as it did back then. If you want to change the world, fill a bag with dirt and give it a name. The world will come running.

Last year, Kevin Slavin argued that the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is engineering people to create online cat memes. Well, which is it fellas? Is kitty litter responsible for Nyan Cat or is Toxoplasma gondii to blame?

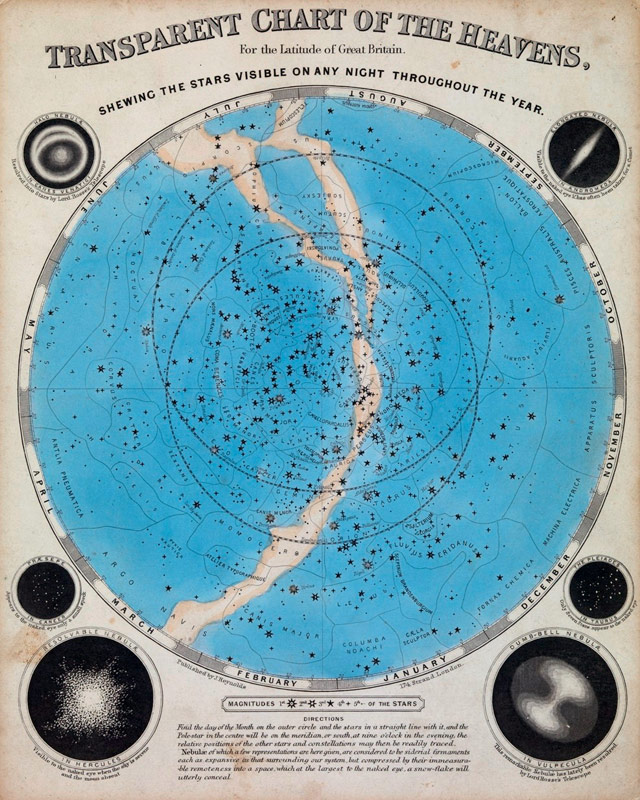

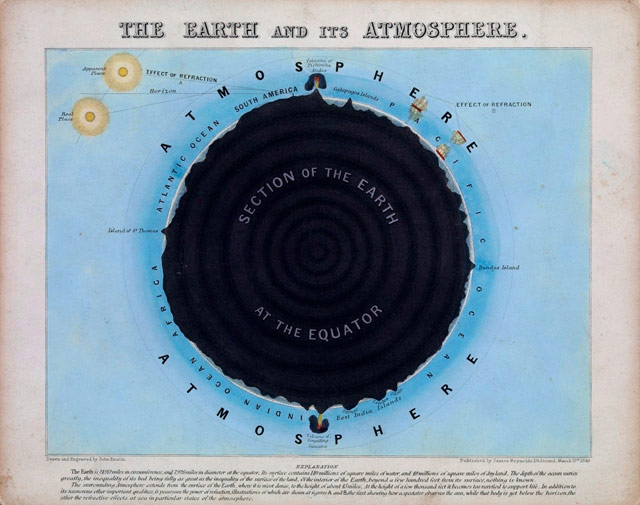

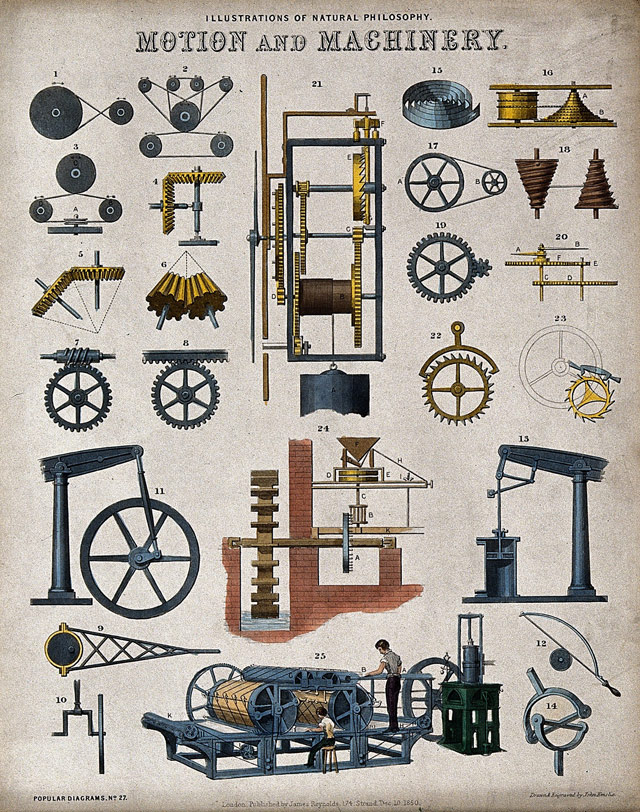

These maps, diagrams, and charts by John Philipps Emslie done in the mid-to-late 1800s are gorgeous.

Intrigued, I went searching for more examples. I loved this one just for pure compositional beauty:

And this lithograph from 1850 showing various machines of the time:

(thx, greg)

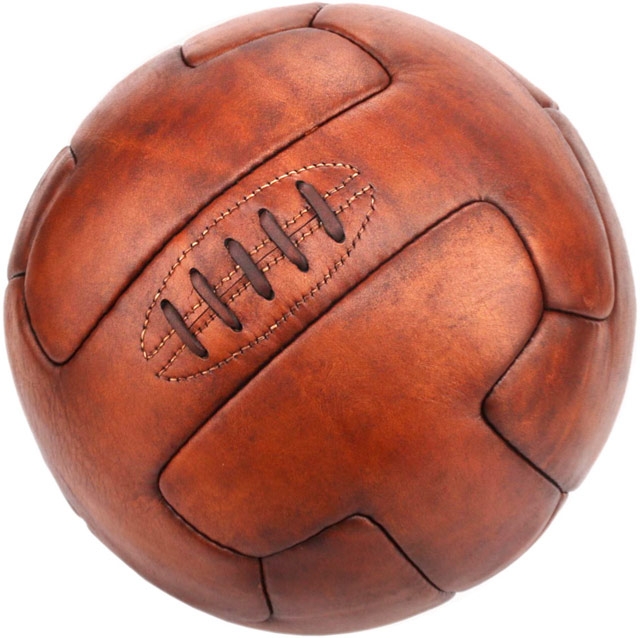

The NY Times has an interactive look at the balls used in the World Cup from 1930 onward. Here’s the ball from 1930:

Look at those laces! Just like the ol’ American handegg.

I’ve seen the waterfalls and the hot springs and the rocky desolation, but I didn’t know that Iceland was also this:

I mean, come on. Photos by Max Rive, Menno Schaefer, and Johnathan Esper. Many more here. (via mr)

Journalist Miles O’Brien lost his left arm in February. He wrote about the experience and what he’s learned from it so far for New York magazine.

But here are two things you need to know about life after an arm amputation: First, your center of gravity changes dramatically when you are suddenly eight pounds lighter on one side of your body. Second, while my arm may be missing physically, it is there, just as it always has been, in my mind’s eye. I can feel every digit. I can even feel the watch that was always strapped to my left wrist. When I tripped, I reached reflexively to break my very real fall with my completely imaginary left hand. My fall was instead broken by my nose, and my nose was broken by my fall.

Lying on that sidewalk, moaning in pain, I reached the end of Denial River and flowed into the Sea of Doubt. It finally dawned on me in that instant that I was, indeed, handicapped. That may not be the term of choice these days — “differently abled” or “physically challenged” may be de rigueur — but as I touched my bloody face, feeling embedded chips of concrete in the wounds, “handicapped” sure seemed to fit.

The woman I was passing on the sidewalk when I fell took one look at me and cried out in panic to her husband: “My God, what’s happened to his arm?” “It’s gone,” I said. “But don’t worry, that didn’t happen today.”

O’Brien also mentions he’s tried mirror therapy pioneered by V.S. Ramachandran, which I’ve written about previously.

Here’s Louis C.K. at 20 years old doing a stand-up routine in Boston in 1987.

Thankfully, he got better. A lot better. Even 3-4 years later he was better…and wait, is that Phil Hartman in the audience at ~2:45?! (via open culture)

Dang, Tesla just announced they’re letting anyone use their patented technology. CEO Elon Musk:

Yesterday, there was a wall of Tesla patents in the lobby of our Palo Alto headquarters. That is no longer the case. They have been removed, in the spirit of the open source movement, for the advancement of electric vehicle technology.

Tesla Motors was created to accelerate the advent of sustainable transport. If we clear a path to the creation of compelling electric vehicles, but then lay intellectual property landmines behind us to inhibit others, we are acting in a manner contrary to that goal. Tesla will not initiate patent lawsuits against anyone who, in good faith, wants to use our technology.

Damn good move for a damn good reason. It’s impressive to watch this company in action.

Update: I read that last line quoted above again and perhaps “abandoned” is too strong a word. Glenn Fleishman notes on Twitter:

They did not abandon their patents. They aren’t apparently even licensing them. They are stating they won’t sue except defensively. The devil is in the details. Twitter released a complete framework of their policy when they announced the same thing.

Hopefully Musk and co. will clarify what they mean by “in good faith”.

Today at 3pm, I’m going to pick up my 6-year-old son and his friends at school and bring them back to my place for his early birthday party. We’re going to watch The Lego Movie, eat popcorn, scarf pizza, and demolish a bunch of mini cupcakes. Everyone is excited.

Today at 3pm, Eric Meyer and his family will be holding a funeral service for his 6-year-old daughter. Rebecca Meyer died on Saturday on her 6th birthday after a months-long battle against cancer. I have been following along as Eric has written beautifully and powerfully about his daughter’s illness and the family’s search for treatments. Each new piece of bad news was tough to read, and her death devastated me.

Sometimes parents tend to get caught up in the minutia of parenthood: the logistics of getting from one place to another without losing your shit, the weary deflection of the 34th “why?” question of the afternoon, and all the rest. At least, I know I do. You forget to lift your head up to appreciate what you have. Author Elizabeth Stone once wrote that having kids was deciding to “have your heart go walking around outside your body”. Steve Jobs put it similarly: your children are “your heart running around outside your body”. That’s the truest sentiment I’ve ever read about parenting; it feels exactly like that to me. Reading Eric’s writing about Rebecca, a girl so close in age to both my kids, has affected me greatly. That could be me. My kids suffering. My heart, broken and dying. Imagining one of them…I can’t even do it, the tears come hard and fast, washing away any such thoughts.

Those dark sad thoughts of mine have to be but a tiny fraction of what Eric and his family are feeling right now and in the months to come. Their heart is gone forever. Eric, I will be thinking about you and your family this afternoon even as we celebrate our happy event, while appreciating what I have more than ever. Rest in peace, Rebecca.

Note: In memory of Rebecca, the text of this post is purple, her favorite color.

A group led by Dr. Robert Costanza has calculated the value of the world’s ecosystems…the group’s most recent estimate puts the yearly value at $142.7 trillion.

“I think this is a very important piece of science,” said Douglas J. McCauley of the University of California, Santa Barbara. That’s particularly high praise coming from Dr. McCauley, who has been a scathing critic of Dr. Costanza’s attempt to put price tags on ecosystem services.

“This paper reads to me like an annual financial report for Planet Earth,” Dr. McCauley said. “We learn whether the dollar value of Earth’s major assets have gone up or down.”

The group last calculated this value back in 1997 and it rose sharply over the past 17 years, even as those natural habitats are disappearing. This line from the article stunned me:

Dr. Costanza and his colleagues estimate that the world’s reefs shrank from 240,000 square miles in 1997 to 108,000 in 2011.

Coral reefs shrank by more than half over the past 17 years…I had no idea the reef situation was that bad. Jesus.

The IPPAWARDS has been judging an iPhone photography competition since 2007 and they recently announced the winners of their 2014 competition.

Impressive stuff. I’ve been saying recently that the iPhone 5s is the best camera in the world. Looking back on the 2008 winners, it becomes apparent how much more comfortable photographers have become wielding this increasingly powerful device. (via the verge)

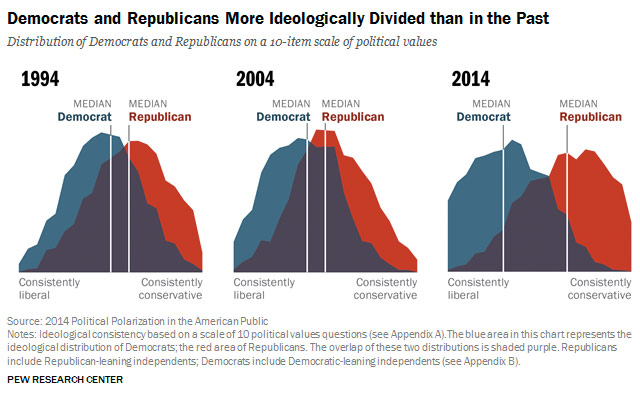

The Pew Research Center has data and visualizations showing how much more polarized Americans have become about their politics over the past 20 years.

In 1994, the overlap was much greater than it is today. Twenty years ago, the median Democrat was to the left of 64% of Republicans, while the median Republican was to the right of 70% of Democrats. Put differently, in 1994 23% of Republicans were more liberal than the median Democrat; while 17% of Democrats were more conservative than the median Republican. Today, those numbers are just 4% and 5%, respectively.

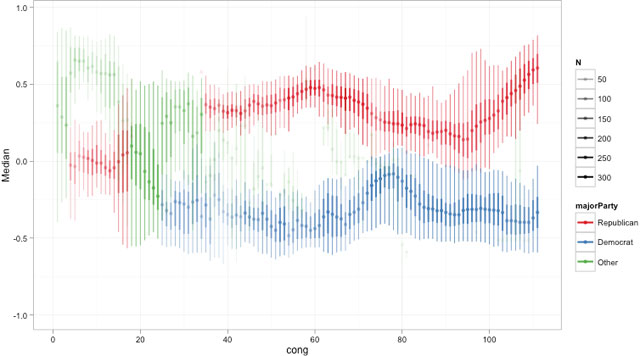

Even more pronounced is the shift by the Republican members of Congress toward the right.

(via @mulegirl)

We’ve been listening to this quite a bit at home lately: Motown: The Complete No. 1’s.

That’s more than twelve hours of music, from The Miracles to Erykah Badu. Some of it, particularly from the 80s, is not so great, but as you listen, you’re of course reminded of how great Stevie Wonder is. Rdio has more than 40 additional hours of Stevie for your listening pleasure. More than 30 hours of the Jackson 5. Hundreds more hours of The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, Commodores, Diana Ross, and on and on. And that’s just riffing off of one album in one genre. Freely choosing from an infinite buffet of choices is a completely different way of listening to music than any of us grew up with (unless you had tons of money or worked in a record store). For me, it’s been an incredible way to take advantage of Tyler Cowen’s observation that there’s way more good unheard stuff in the back catalog than there is new music…e.g. if you haven’t heard John Coltrane’s The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings, it’s likely to be better than most new music you’ll hear this year.

Felix Salmon, who used to blog for Reuters but now works for a new cable TV network, interviews Jonah Peretti of Buzzfeed, a site best known for its lists and snackable meme content, for a site called Matter which is in turn published by Medium. Medium tells us the interview will take 91 minutes to read. Also, I am writing this from the Buzzfeed office and Jonah is a friend of mine.

Jonah is not your typical media mogul, however. He’s smarter than most, and more accessible, and also much happier than many to share his thoughts. Which is why I asked Jonah if he’d be interested in talking to me over an extended period. To my delight, he said yes, and we ended up having four interviews spanning more than six hours.

The resulting Q&A is long, for which I make no apologies. You’ll learn a lot about Jonah Peretti and how he thinks - but you’ll also learn a great deal about the modern media world, the way the Internet has evolved, and the way that Jonah has evolved with it.

If you want to learn the secret of how Jonah managed to build two of the world’s most important online media properties, you’ll find that here, too. Which brings me to another way in which Jonah differs from most other moguls. If you succeed in building something similarly successful as a result, he will be cheering you all the way.

I am looking forward to someone publishing the highlights of this. (via @choire)

Update: Here’s an attempt at some crib notes. (via @tgeorgakopoulos)

Great short film about how ILM’s groundbreaking visual effects came to be used in Jurassic Park.

When Spielberg originally conceived the movie, he was going to use stop-motion dinosaurs. ILM was tasked with providing motion blur to make them look more realistic. But in their spare time, a few engineers made a fully digital T. Rex skeleton and when the producers saw it, they flipped out and scrapped the stop-motion entirely. Fun story.

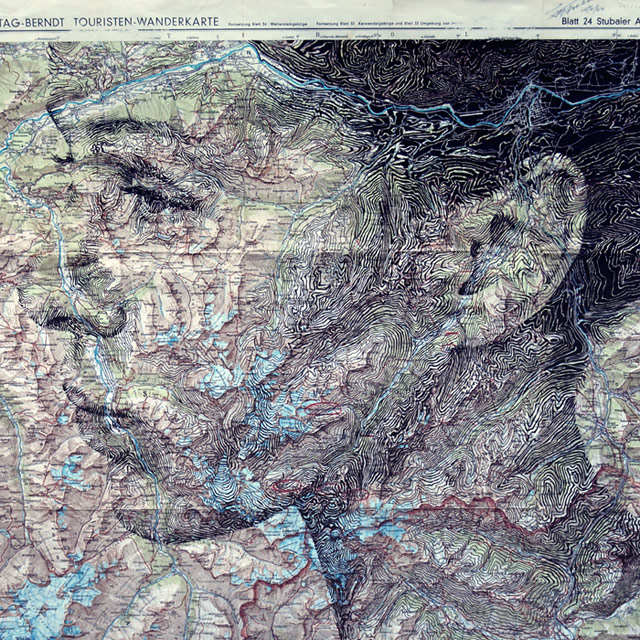

From artist Ed Fairburn, a collection of portraits drawn on top of maps. Reminiscent of Matthew Cusick’s map collages. (via @damienjoyce)

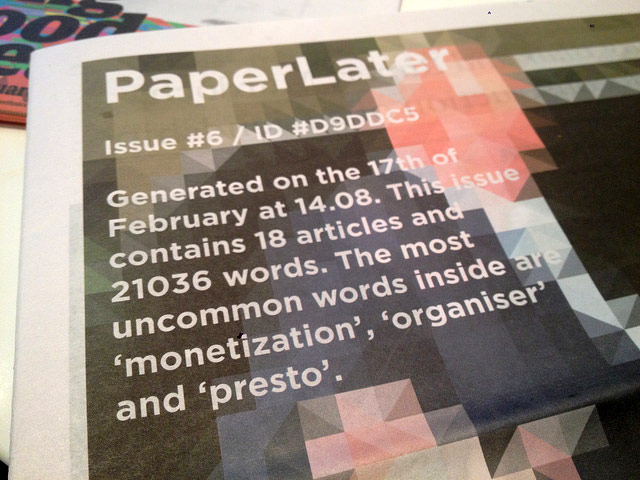

PaperLater is a new service by Newspaper Club. You bookmark articles you want to read and they print it up as a newspaper. Basically a print version of Instapaper.

Rex Sorgatz on how rare media doesn’t really exist anymore.

With access to infinite bytes of media, describing a digital object as “rare” sticks out like a lumbering anachronism. YouTube - the official home of lumbering anachronisms - excels at these extraordinarily contradictory moments. Here, for instance, are the Beatles, performing a “VERY RARE” rendition of “Happy Birthday”. That sonic obscurity has been heard 2.3 million times. And here is a “Rare Acoustic” version of Slash performing “Sweet Child O’ Mine”. Over 26 million have devoured this esoteric Axl-less morsel.

One way or another, Bitcoin is going to be huge. It could be the as big as the Internet, it could transform into something else, or it could be one of tech’s biggest busts. Meanwhile, many of us are still wondering exactly what it is (it’s both a currency and means of transporting that currency). GQ’s Marshall Sella decided to score some of this newfangled dough and “blow it on all the pleasures that Bitcoin can buy.” Sex, Drugs, and Toasters: My Life on Bitcoin.

Within two months, I’d be visiting Charlie Shrem at his parents’ place, where he was wearing an ankle monitor and living under house arrest.

(That sounds like the beginning of every great startup story.)

Kwe’Shaun Parker is a 6’2” high-school sophomore and recently threw down one of the sickest dunks of the year:

Dang! I mean, DANG! Here’s Parker last year as a freshman doing some equally amazing stuff:

(via @cory_arcangel)

After thumbing through a copy at my local bar the other night, I’ve had my eye on Jeffrey Morgenthaler’s new book, The Bar Book: Elements of Cocktail Technique.

Written by renowned bartender and cocktail blogger Jeffrey Morgenthaler, The Bar Book is the only technique-driven cocktail handbook out there. This indispensable guide breaks down bartending into essential techniques, and then applies them to building the best drinks. More than 60 recipes illustrate the concepts explored in the text, ranging from juicing, garnishing, carbonating, stirring, and shaking to choosing the correct ice for proper chilling and dilution of a drink. With how-to photography to provide inspiration and guidance, this book breaks new ground for the home cocktail enthusiast.

I’ve been beefing up my home bar over the past few weeks and hopefully this book will help me along in the technique department. Nothing in there about catching glasses behind your back, but no book is perfect, I guess. (thx, gabe)

From Grantland’s Mike Goodman, a guide to nerding out about soccer, using the language already spoken by American sports nerds.

What exactly is a good shot in soccer? The nascent field of soccer analytics is hard at work trying to figure that out. It won’t surprise anybody to learn that closer is better, and using your feet is much, much better than using your head. So, much like getting into the lane is of paramount importance in basketball, getting the ball at your feet in front of the goal is just about the best thing you can do in soccer. Getting to the byline (baseline) in the corner of the penalty areas (like where Maicon was in the above video) is a hot destination. That’s where you can cut the ball back for a teammate to have one of those coveted close shots. Hey, look at that - it’s like basketball again: Get to the goal or get to the corners.

I saw the trailer for the new Planet of the Apes movie last night and it looks amazing, but that’s not what I came to talk about. A recent paper shows that chimps do better in some strategy games than humans.

Chimps play the cat and mouse game very well. First, the chimps converge on the Nash Equilibrium strategies. In one set of games the Nash equilibrium strategies had randomization frequencies of .5, .75 and .8 and the chimps played .5, .73 and .79. Second, when payoffs change the chimps adapt their strategies very quickly simply by observation of outcomes.

Camerer et al. also tested humans in similar games and they found that humans often deviate from NE play and they adjust their strategies more slowly when payoffs change, i.e. they learn more slowly! The only thing that Camerer didn’t do was to play humans against chimps in the same game. That would have been awesome!

But that’s nothing compared to this video of a chimp remembering the placement of nine numbers on a screen after seeing them for less than a quarter of a second:

That’s a literal jaw-dropper there.

Anthony Richardson is back, offering his British commentary on American sports. This time it’s hockey:

Mary Poppins, look how small the goals are, the size of a matchbox guarded by an overzealous beekeeper.

See also Bad British NFL commentary and Bad British baseball commentary.

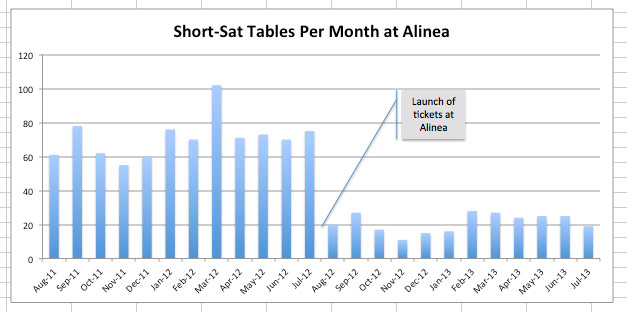

For three years, Nick Kokonas’s trio of eating/drinking establishments in Chicago (Next, Alinea, and Aviary) has been using a ticketed reservation system. In this epic piece, Kokonas details why they started using tickets and what the effect has been (emphasis mine):

Our ticket implementation strategy at Alinea was to create a “higher-touch” system than we had previously used at Next. Every customer buying a ticket at Alinea must include a cell phone number where we can reach them. About a week before they dine with us we call every customer to thank them for buying a ticket to Alinea, ask if they have any dietary restrictions or special needs, and generally get a feel for their expectations and whether it is a special occasion. We can, in fact, spend more time (not less) with every single one of our customers because we are only speaking with the customers we know are coming to dine with us. Previously, we answered thousands of calls from people we had to say ‘no’ to. Now we can take far more time to say ‘yes’.

The results on Alinea’s business are staggering. Bottom line EBITDA profits are up 38% from previous average years. No shows of full tables are almost non-existent and while partial no-shows still occur they are only a handful of people per week at most. That allows us to run at a far greater capacity with less food waste and more revenue.

Will be interesting to see if more restaurants adopt this model…I bet a bunch of restaurateurs’ eyes lit up at the 38% increase in profit. But not every restaurant is Alinea and not every restaurateur is a clever former derivatives trader.

A supercomputer running a program simulating a 13-year-old boy named Eugene has passed the Turing Test at an event held at London’s Royal Society.

The Turing Test is based on 20th century mathematician and code-breaker Turing’s 1950 famous question and answer game, ‘Can Machines Think?’. The experiment investigates whether people can detect if they are talking to machines or humans. The event is particularly poignant as it took place on the 60th anniversary of Turing’s death, nearly six months after he was given a posthumous royal pardon.

If a computer is mistaken for a human more than 30% of the time during a series of five minute keyboard conversations it passes the test. No computer has ever achieved this, until now. Eugene managed to convince 33% of the human judges that it was human.

I’m sure there will be some debate as members of the AI and computing communities weigh in over the next few days, but at first blush, it seems like a significant result. The very first Long Bet concerned the Turing Test, with Mitch Kapor stating:

By 2029 no computer — or “machine intelligence” — will have passed the Turing Test.

and Ray Kurzweil opposing. The stakes are $20,000, but the terms are quite detailed, so who knows if Kurzweil has won.

Update: Kelly Oakes of Buzzfeed dumps some cold water on this result.

Of course the Turing Test hasn’t been passed. I think its a great shame it has been reported that way, because it reduces the worth of serious AI research. We are still a very long way from achieving human-level AI, and it trivialises Turing’s thought experiment (which is fraught with problems anyway) to suggest otherwise.

Calvin and Hobbes artist/professional recluse Bill Watterson quietly collaborated with Pearls Before Swine’s Stephan Pastis to write and draw a short sequence of comics that appeared in newspapers this week.

Let me tell you. Just getting an email from Bill Watterson is one of the most mind-blowing, surreal experiences I have ever had. Bill Watterson really exists? And he sends email? And he’s communicating with me?

But he was. And he had a great sense of humor about the strip I had done, and was very funny, and oh yeah….

…He had a comic strip idea he wanted to run by me.

Now if you had asked me the odds of Bill Watterson ever saying that line to me, I’d say it had about the same likelihood as Jimi Hendrix telling me he had a new guitar riff. And yes, I’m aware Hendrix is dead.

So I wrote back to Bill.

“Dear Bill,

I will do whatever you want, including setting my hair on fire.”

All Watterson asked was that the original artwork be auctioned off for charity, and that Pastis not reveal the trick until it was complete.

Pastis did tip his hand a little on Twitter — how could he not? — writing that “this week’s Pearls strips will contain a mind-blowing surprise,” which led some people to take a good look at the artwork (and the lettering — it’s the lettering that gives it away) and put two and two together.

In an interview, Watterson tells the Washington Post’s Michael Cavna that the motivating impulse for his temporary return was to raise money for a charity founded by Post cartoonist (and close Watterson friend) Richard Thompson:

Thompson, a longtime Washington Post artist who lives in Arlington, Va., ended his Reuben Award-winning syndicated strip “Cul de Sac” in 2012 as he underwent therapy and surgery to treat his Parkinson’s; Watterson is an enormous fan of Thompson’s, and the two now have a dual exhibit at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus.

“I thought maybe Stephan and I could do this goofy collaboration and then use the result to raise some money for Parkinson’s research in honor of Richard Thompson,” Watterson tells me. “It just seemed like a perfect convergence.”

The conceit of this week in Pearls Before Swine is that the cartoonist protagonist meets his neighbor Libby, who takes over drawing his comic. (Libby is in second grade, roughly the same age as Calvin, and her name is a play on “Bill.”)

My favorite of the strips is easily Thursday’s, where a talking-head pig and mouse are interrupted by a beautifully-drawn Martian robot attack.

“I could do better if I had more space,” Libby gripes — a nod to Watterson’s famous insistence on only syndicating the Sunday strip of Calvin and Hobbes if it could be printed in full.

But the whole week is worth reading. Start with Monday’s and keep clicking right until you run out of Libby. And let us never cease from exploration, but at the end of all our exploring arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

(Thanks to Bill Wasik, Susie Cagle, and TS Eliot)

Louis C.K. sat down with Jonah Weiner for an extended interview where he discusses learning how to fix cars, tell jokes, fry chicken, and more. (Seriously, Medium is milking that whole time spent reading thing now.) He also gives some clues as to what he seems to be up to in the current season of Louie:

JW: You’ve talked about how you’ve had to explain moral lessons to your daughters, but do it in a catchy way. It’s almost as though you’re writing material for them. What’s the place of morality and ethics in your comedy?

I think those are questions people live with all the time, and I think there’s a lazy not answering of them now, everyone sheepishly goes, “Oh, I’m just not doing it, I’m not doing the right thing.” There are people that really live by doing the right thing, but I don’t know what that is, I’m really curious about that. I’m really curious about what people think they’re doing when they’re doing something evil, casually. I think it’s really interesting, that we benefit from suffering so much, and we excuse ourselves from it. I think that’s really interesting, I think it’s a profound human question…

I think it’s really interesting to test what people think is right or wrong, and I can do that in both directions, so sometimes it’s in defense of the common person against the rich that think they’re entitled to this shit, but also the idea that everybody has to get handouts and do whatever they want so that there’s not supposed to be any struggle in life is also a lot of horseshit. Everything that people say is testable.

At the LA Review of Books, Lili Loofbourow has a good essay about Louie’s abrupt shifts in perspective, in the context of its recent rape-y episodes. There’s Louie the dad, who garners sympathy and acts as a cover/hedge/foil to Louie’s darker impulses. There’s standup Louie, who acts as a commentary and counterpoint to dramedy Louie… except when he doesn’t, and the two characters blur and flip.

Louie is — despite its dick-joke dressing — a profoundly ethical show… Louie is sketching out the psychology of an abuser by making us recognize abuse in someone we love. Someone thoughtful and shy, raising daughters of his own, doing his best. Someone totally cognizant of the issues that make him susceptible to the misogyny monster. Someone who thinks hard about women and men and still gets it badly wrong.

I had to stop watching Louie after Season 1. I raced greedily through those episodes, enjoying the dumb jokes and the sophisticated storytelling, and telling my friends, “this is like looking at my life in ten years.” Then my wife and I separated and that joke wasn’t funny any more, if it ever was. The things in Louie that are supposed to indicate the cracks in the fourth wall — the African-American ex-wife and the seemingly white children — are actually true in my life. His character is more like me than his creator is (except Louie has more money). No haha, you’re both redheads with beards. It’s an honest-to-goodness uncanny valley. I had to walk away.

At the same time, I feel like I understand Louis C.K., the comedian/filmmaker, better now than I did three years ago. If you read that interview, you see someone who’s more successful now than he’s ever been, who knows he’s good at what he does, but who’s never been certain that anyone’s ever loved him or if he’s ever been worthy of love.

Now America loves Louis C.K. and hangs on his every word: on gadgets, on tests in school, on what’s worth caring about. How can he not want to test those limits? How can he not want to punish his audience for caring about a character based on him that he doesn’t even like very much?

A short profile of writer/editor Roger Angell, still coming in to work most days at The New Yorker at age 93:

Angell saw Babe Ruth in his prime, but he never writes sentimentally about baseball, a sport that has inspired many sports-writers to produce reams of awful, faux-poetic prose. His habit of telling it straight is what makes his nine books hold up and keeps him relevant today. “I don’t go for nostalgia,” he says. “I try not to. It’s so easy to sentimentalize the good old days, but I don’t ever do that. I’m aware that things have changed, but I try not to go there. It’s very easy, and you get sort of a mental diabetes. All that goo. I am a foe of goo, maybe too much so.”

Angell’s extended essay “This Old Man” offers an extended dose of that lucidity.

Here in my tenth decade, I can testify that the downside of great age is the room it provides for rotten news. Living long means enough already. When Harry [Angell’s fox terrier] died, Carol and I couldn’t stop weeping; we sat in the bathroom with his retrieved body on a mat between us, the light-brown patches on his back and the near-black of his ears still darkened by the rain, and passed a Kleenex box back and forth between us. Not all the tears were for him. Two months earlier, a beautiful daughter of mine, my oldest child, had ended her life, and the oceanic force and mystery of that event had not left full space for tears. Now we could cry without reserve, weep together for Harry and Callie and ourselves. Harry cut us loose.

Anyone who’s been writing for a long time has tools they like and come to depend on; one of Angell’s is a discontinued Mead three-subject notebook:

The best notebook in the world. David Remnick and I talk about how you can’t get anything to replace the Mead notebook, which is unavailable now. They take ink perfectly. There is a great flow. All the other notebooks are coated with something so your pen slides along.

“In recent years, when he goes on reporting trips,” Angell’s interviewer notes, “he has resorted to making use of old Mead notebooks that still have blank pages.”

Today is National Donut/Doughnut Day, apparently a relatively venerable holiday with roots in a Depression-era Salvation Army giveaway. But just how do you spell that “edible, torus-shaped piece of dough which is deep-fried and sweetened”?

The Official Dictionary Spelling of the word in question—if you’re into that sort of thing—is “doughnut.” The expedited, simplified, Americanized spelling of “donut,” as Grammarist tells us, has been around since at least the late 19th century. It didn’t catch on, though, until late in the 20th century.

Why? That’s when Massachusetts-based chain Dunkin’ Donuts first started taking off — so thank (or blame) Dunkin’ for the popularity of the “Donut” spelling.

Historically, I’ve bowed to usage on this one and spelled it “donut” (just like I use “catalog” and other Americanized spellings that are more than a century old). But Dick Wisdom has an informal survey that shows that even professional publications are torn on which spelling to prefer. Even that quintessentially British, infinitely rule-observing Reuters has been known to publish either spelling.

As a professional journalist, I’ve learned to follow the style guide and keep my private grumblings about grammar and usage confined to Twitter, email, IRC, and viva voce conversation. So for clarity, I asked: what does Jason do? (I did the same thing yesterday to decide whether or not to put “Lego” in all-caps.)

For kottke.org, Jason overwhelmingly prefers “donut.” The vast majority of “doughnut” spellings found on the site are direct quotes (which kottke.org normally does not adapt to match house style). There are some really fun posts about donuts, too, including 2003’s “A Fun Thing I’ll Do Again”:

I have tasted a donut so hot and delicious that I burned my fingers eating it but did not stop to put it down. I have eaten foie gras creme brulee and heard tale of a foie gras donut.

Still, even here, we see a stray native spelling of “doughnut”:

This video is too long and come frontloaded with too much explanation, but like a jelly doughnut, there’s some goodness in the middle