kottke.org posts about Uber

I read four things recently that are all related in some way to our cities and how we get around in them.

1. Was the Automotive Era a Terrible Mistake? by Nathan Heller in the New Yorker. The subtitle is “For a century, we’ve loved our cars. They haven’t loved us back.”

For years, I counted this inability to drive as one of many personal failures. More recently, I’ve wondered whether I performed an accidental kindness for the world. I am one of those Darth Vader pedestrians who loudly tailgate couples moving slowly up the sidewalk, and I’m sure that I would be a twit behind the wheel. Perhaps I was protected from a bad move by my own incompetence-one of those mercies which the universe often bestows on the young (who rarely appreciate the gift). In America today, there are more cars than drivers. Yet our investment in these vehicles has yielded dubious returns. Since 1899, more than 3.6 million people have died in traffic accidents in the United States, and more than eighty million have been injured; pedestrian fatalities have risen in the past few years. The road has emerged as the setting for our most violent illustrations of systemic racism, combustion engines have helped create a climate crisis, and the quest for oil has led our soldiers into war.

Every technology has costs, but lately we’ve had reason to question even cars’ putative benefits. Free men and women on the open road have turned out to be such disastrous drivers that carmakers are developing computers to replace them. When the people of the future look back at our century of auto life, will they regard it as a useful stage of forward motion or as a wrong turn? Is it possible that, a hundred years from now, the age of gassing up and driving will be seen as just a cul-de-sac in transportation history, a trip we never should have taken?

2. This comment from the NY Times’ list of The Summer’s Hottest Takes on the amount of public space (and funds) that’s given to cars in our cities.

City street parking should be considered public space. The current setup is ridiculous: In front of millions of New Yorkers’ apartments, for one example, there are 9-by-18-foot plots of space, available to anyone in the city… if they have a car and want to leave it there. Less than half of the city’s residents own cars, and far fewer can lay claim to any kind of outdoor space. So from Fort Worth to Philadelphia, why not let people use these patches of cement for something they can actually enjoy? Let people set up a table with some food, a little grill, a folding table to sit at and enjoy the sun, and each other. Make space next to the sidewalk. Hatch 10,000 tiny little public spaces in cities that are starved for some life.

3. Why Am I Scared to Ride a Bike?, a comic by Vreni at The Nib.

4. I Don’t Use Uber. Neither Should You. by Paris Marx, who says that “the tradeoffs are far too high for a little more convenience”.

A study of seven major U.S. metro areas from UC Davis showed that 91 percent of ride-hailing users didn’t make any changes to their car ownership status, and those that did made up for the reduced miles driven by taking more ride-hail trips. The researchers also found that 49 to 61 percent of all ride-hailing trips wouldn’t have been taken or would have used transit, cycling, or walking had ride-hailing not been an option. Another study by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council put that number at 59 percent in Boston.

Those are key figures because they show that Uber, Lyft, and their competitors not only add car trips in urban centers, they also make existing trips less efficient by shifting them from transit or cycling into a car. This process makes traffic congestion worse because it places more vehicles on the road.

See also this recent post, America’s Cars Are Heavily Subsidized, Dangerous, and Mandatory.

Hubert Horan’s broadside of Uber for American Affairs starts out like this and doesn’t let up:

Since it began operations in 2010, Uber has grown to the point where it now collects over $45 billion in gross passenger revenue, and it has seized a major share of the urban car service market. But the widespread belief that it is a highly innovative and successful company has no basis in economic reality.

An examination of Uber’s economics suggests that it has no hope of ever earning sustainable urban car service profits in competitive markets. Its costs are simply much higher than the market is willing to pay, as its nine years of massive losses indicate. Uber not only lacks powerful competitive advantages, but it is actually less efficient than the competitors it has been driving out of business.

This is one of those articles where I want to excerpt the entire thing; it’s just so jammed packed with goodies about a company that represents everything I hate about “tech” and Silicon Valley.

In reality, Uber’s platform does not include any technological breakthroughs, and Uber has done nothing to “disrupt” the economics of providing urban car services. What Uber has disrupted is the idea that competitive consumer and capital markets will maximize overall economic welfare by rewarding companies with superior efficiency. Its multibillion dollar subsidies completely distorted marketplace price and service signals, leading to a massive misallocation of resources. Uber’s most important innovation has been to produce staggering levels of private wealth without creating any sustainable benefits for consumers, workers, the cities they serve, or anyone else.

A later section is titled “Uber’s Narratives Directly Copied Libertarian Propaganda”.

In the early 1990s, a coordinated campaign advocating taxi deregulation was conducted by a variety of pro-corporate/libertarian think tanks that all received funding from Charles and David Koch. This campaign pursued the same deregulation that Uber’s investors needed, and used classic political propaganda techniques. It emphasized emotive themes designed to engage tribal loyalties and convert complex issues into black-and-white moral battles where compromise was impossible. There was an emphasis on simple, attractive conclusions designed to obscure the actual objectives of the campaigners, and their lack of sound supporting evidence.

This campaign’s narratives, repeated across dozens of publications, included framing taxi deregulation as a heroic battle for progress, innovation, and economic freedom. Its main claims were that thousands of struggling entrepreneurial drivers had been blocked from job opportunities by the “cab cartel” and the corrupt regulators beholden to them, and that consumers would enjoy the same benefits that airline deregulation had produced. In a word, consumers were promised a free lunch. Taxi deregulation would lead to lower fares, solve the problems of long waits, provide much greater service (especially in neighborhoods where service was poor), and increase jobs and wages for drivers. Of course, no data or analysis of actual taxi economics showing how these wondrous benefits could be produced was included.

Horan reserves a healthy chunk of his criticism for the media, whose unwillingness to critically cover the company — “the press refuses to reconsider its narrative valorizing Uber as a heroic innovator that has created huge benefits for consumers and cities” — has provided a playbook for future investors to exploit for years to come. Blech. What a shitshow.

At Streetsblog, Angie Schmitt has compiled a handy list of all the ways in which ride sharing services like Uber and Lyft are having significant negative effects on our cities, the environment, and our health.

Uber and Lyft are just crushing transit service in the U.S. A recent study estimated, for example, they had reduced bus ridership in San Francisco, for example, 12 percent since 2010 — or about 1.7 percent annually. And each year the services are offered, the effect grows, researcher Gregory Erhardt found.

Every person lured from a bus or a train into a Lyft or Uber adds congestion to the streets and emissions to the air. Even in cities that have made tremendous investments in transit — like Seattle which is investing another $50 billion in light rail — Uber and Lyft ridership recently surpassed light rail ridership.

Transit agencies simply cannot complete with private chauffeur service which is subsidized at below real costs by venture capitalists.

Uber and Lyft (and their investors) clearly aren’t going to stop…it’s up to cities and communities to take action. They can’t just let these companies ruin their transit until ride sharing is the only thing left.

A slew of transportation companies, including Uber, Lyft, Zipcar, Didi, and Citymapper recently signed the Shared Mobility Principles for Livable Cities, which are:

1. We plan our cities and their mobility together.

2. We prioritize people over vehicles.

3. We support the shared and efficient use of vehicles, lanes, curbs, and land.

4. We engage with stakeholders.

5. We promote equity.

6. We lead the transition towards a zero-emission future and renewable energy.

7. We support fair user fees across all modes.

8. We aim for public benefits via open data.

9. We work towards integration and seamless connectivity.

10. We support that autonomous vehicles in dense urban areas should be operated only in shared fleets.

This all sounds good, but there’s not a lot of emphasis on public transportation, aside from this (and a couple of other mentions):

The mobility of people and not vehicles shall be in the center of transportation planning and decision-making. Cities shall prioritize walking, cycling, public transport and other efficient shared mobility, as well as their interconnectivity. Cities shall discourage the use of cars, single-passenger taxis, and other oversized vehicles transporting one person.

I remain skeptical that Uber’s ultimate goal isn’t to replace any and every public transportation system it can.

In Drive 2, Ryan Gosling trades his robbery getaway driving gig for driving for Uber.

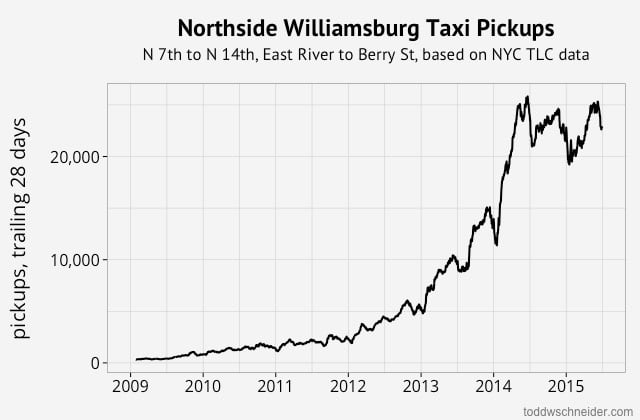

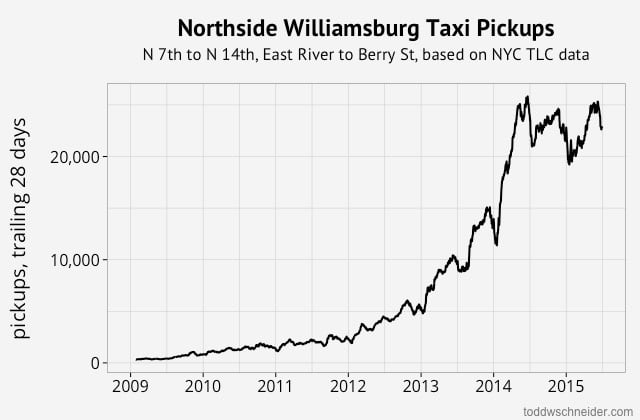

Todd Schneider used a couple publicly available data sets (NYC taxis, Uber) to explore various aspects of how New Yorkers move about the city. Some of the findings include the rise of Uber:

Let’s add Uber into the mix. I live in Brooklyn, and although I sometimes take taxis, an anecdotal review of my credit card statements suggests that I take about four times as many Ubers as I do taxis. It turns out I’m not alone: between June 2014 and June 2015, the number of Uber pickups in Brooklyn grew by 525%! As of June 2015, the most recent data available when I wrote this, Uber accounts for more than twice as many pickups in Brooklyn compared to yellow taxis, and is rapidly approaching the popularity of green taxis.

…the plausibility of Die Hard III’s taxi ride to stop a subway bombing:

In Die Hard: With a Vengeance, John McClane (Willis) and Zeus Carver (Jackson) have to make it from 72nd and Broadway to the Wall Street 2/3 subway station during morning rush hour in less than 30 minutes, or else a bomb will go off. They commandeer a taxi, drive it frantically through Central Park, tailgate an ambulance, and just barely make it in time (of course the bomb goes off anyway…). Thanks to the TLC’s publicly available data, we can finally address audience concerns about the realism of this sequence.

…where “bridge and tunnel” folks go for fun in Manhattan:

The most popular destinations for B&T trips are in Murray Hill, the Meatpacking District, Chelsea, and Midtown.

…the growth of north Williamsburg nightlife:

…the privacy implications of releasing taxi data publicly:

For example, I don’t know who owns one of theses beautiful oceanfront homes on East Hampton’s exclusive Further Lane (exact address redacted to protect the innocent). But I do know the exact Brooklyn Heights location and time from which someone (not necessarily the owner) hailed a cab, rode 106.6 miles, and paid a $400 fare with a credit card, including a $110.50 tip.

as well as average travel times to the city’s airports, where investment bankers live, and how many people pay with cash vs. credit cards. Read the whole thing and if you want to play around with the data yourself, Schneider posted all of his scripts and knowhow on Github.

Update: Using summaries published by the New York City Taxi & Limousine Commission, Schneider takes a look at how taxi usage in NYC is shrinking and how usage of Uber is growing.

This graph will continue to update as the TLC releases additional data, but at the time I wrote this in April 2016, the most recent data shows yellow taxis provided 60,000 fewer trips per day in January 2016 compared to one year earlier, while Uber provided 70,000 more trips per day over the same time horizon.

Although the Uber data only begins in 2015, if we zoom out to 2010, it’s even more apparent that yellow taxis are losing market share.

Lyft began reporting data in April 2015, and expanded aggressively throughout that summer, reaching a peak of 19,000 trips per day in December 2015. Over the following 6 weeks, though, Lyft usage tumbled back down to 11,000 trips per day as of January 2016 — a decline of over 40%.

The trolley problem is an ethical and psychological thought experiment. In its most basic formulation, you’re the driver of a runaway trolley about to hit and certainly kill five people on the track ahead, but you have the option of switching to a second track at the last minute, killing only a single person. What do you do?

The problem becomes stickier as you consider variations of the problem:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you — your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

As driverless cars and other autonomous machines are increasingly on our minds, so too is the trolley problem. How will we program our driverless cars to react in situations where there is no choice to avoid harming someone? Would we want the car to run over a small child instead of a group of five adults? How about choosing between a woman pushing a stroller and three elderly men? Do you want your car to kill you (by hitting a tree at 65mph) instead of hitting and killing someone else? No? How many people would it take before you’d want your car to sacrifice you instead? Two? Six? Twenty? Is there a place in the car’s system preferences panel to set the number of people? Where do we draw those lines and who gets to decide? Google? Tesla? Uber?1 Congress? Captain Kirk?

If that all seems like a bit too much to ponder, Kyle York shared some lesser-known trolley problem variations at McSweeney’s to lighten the mood.

There’s an out of control trolley speeding towards a worker. You have the ability to pull a lever and change the trolley’s path so it hits a different worker. The first worker has an intended suicide note in his back pocket but it’s in the handwriting of the second worker. The second worker wears a T-shirt that says PLEASE HIT ME WITH A TROLLEY, but the shirt is borrowed from the first worker.

Reeeeally makes you think, huh?

Software developer and free software advocate Richard Stallman lists several reasons why using Uber is not a good idea. Stallman is definitely a hardliner1, but I agree with several of his points here. (via hacker news)

Mobile devices and software advances have helped to create a burgeoning on-demand economy that — in some places — makes it possible to live your life without leaving your house (and if you do decide to leave, it’s easy to order a car). But that’s only part of the story. In Quartz, Leo Mirani explains how he experienced the on-demand economy long before tech revolution:

These luxuries are not new. I took advantage of them long before Uber became a verb, before the world saw the first iPhone in 2007, even before the first submarine fibre-optic cable landed on our shores in 1997. In my hometown of Mumbai, we have had many of these conveniences for at least as long as we have had landlines — and some even earlier than that. It did not take technology to spur the on-demand economy. It took masses of poor people.

Paul Ford imagines a future where Uber is the largest company in the world, controlling much of humanity’s transportation and delivery needs.

I am Uber. I believed to 0.56 certainty that I could find a bicycle for the person doing the delivery and provide that person with a discounted rental fee. Unfortunately the city of New York insists that bicycle rental kiosks must be controlled by an entity that is not Uber and thus I am not granted the level of full control that is necessary for me to truly optimize the city. No one benefits, no one at all.

An instant classic John Gruber post about the sort of company Apple is right now and how it compares in that regard to its four main competitors: Google, Samsung, Microsoft, and Amazon. The post is also about how Apple is now firmly a Tim Cook joint, and the company is better for it.

When Cook succeeded Jobs, the question we all asked was more or less binary: Would Apple decline without Steve Jobs? What seems to have gone largely unconsidered is whether Apple would thrive with Cook at the helm, achieving things the company wasn’t able to do under the leadership of the autocratic and mercurial Jobs.

Jobs was a great CEO for leading Apple to become big. But Cook is a great CEO for leading Apple now that it is big, to allow the company to take advantage of its size and success. Matt Drance said it, and so will I: What we saw last week at WWDC 2014 would not have happened under Steve Jobs.

This is not to say Apple is better off without Steve Jobs. But I do think it’s becoming clear that the company, today, might be better off with Tim Cook as CEO. If Jobs were still with us, his ideal role today might be that of an eminence grise, muse and partner to Jony Ive in the design of new products, and of course public presenter extraordinaire. Chairman of the board, with Cook as CEO, running the company much as he actually is today.

This bit on the commoditization of hardware, and Apple’s spectacularly successful fight against it, got me thinking about current events. Here’s Gruber again:

Apple’s device-centric approach provides them with control. There’s a long-standing and perhaps everlasting belief in the computer industry that hardware is destined for commoditization. At their cores, Microsoft and Google were founded on that belief - and they succeeded handsomely. Microsoft’s Windows empire was built atop commodity PC hardware. Google’s search empire was built atop web browsers running on any and all computers. (Google also made a huge bet on commodity hardware for their incredible back-end infrastructure. Google’s infrastructure is both massive and massively redundant - thousands and thousands of cheap hardware servers running custom software designed such that failure of individual machines is completely expected.)

This is probably the central axiom of the Church of Market Share - if hardware is destined for commoditization, then the only thing that matters is maximizing the share of devices running your OS (Microsoft) or using your online services (Google).

The entirety of Apple’s post-NeXT reunification success has been in defiance of that belief - that commoditization is inevitable, but won’t necessarily consume the entire market. It started with the iMac, and the notion that the design of computer hardware mattered. It carried through to the iPod, which faced predictions of imminent decline in the face of commodity music players all the way until it was cannibalized by the iPhone.

And here’s David Galbraith tweeting about the seemingly unrelated training that London taxi drivers receive, a comment no doubt spurred by the European taxi strikes last week, protesting Uber’s move into Europe:

Didn’t realize London taxi drivers still have to spend years learning routes. That’s just asking to be disrupted http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxicabs_of_the_United_Kingdom#The_Knowledge

Here’s the relevant bit from Wikipedia about The Knowledge:

It is the world’s most demanding training course for taxicab drivers, and applicants will usually need at least twelve ‘appearances’ (attempts at the final test), after preparation averaging 34 months, to pass the examination.

Uber, in this scenario, is attempting to be Microsoft in the 1980s and early 90s. They’re implementing their software layer (the Uber service) on commodity hardware, which includes not only iPhones & Android phones, mass-produced cars of any type, and GPS systems but also, and crucially, the drivers themselves. Uber is betting that a bunch of off-the-shelf hardware, “ordinary” drivers, and their self-service easy-pay dispatch system will provide similar (or even better) results than a fleet of taxi drivers each with three years of training and years of experience. It is unclear to me what the taxi drivers can do in this situation to emulate the Apple of 1997 in making that commoditization irrelevant to their business prospects. Although when it comes to London in particular, Uber may have miscalculated: in a recent comparison at rush hour, an Uber cab took almost three times as long and was 64% more expensive than a black cab.

In response to a question on Quora of how significant transportation startup Uber is, Michael Wolfe offers an answer that isn’t so much about Uber in particular as it is a way of looking at businesses from the perspective of the owners/investors.

If you think of Uber as a town car company operating in a few cities, it is not big.

If you think of Uber as dominating and even growing the town car market in dozens of cities, it gets bigger. (Data point: there are now more Uber black cars in San Francisco than there were ALL black cars before Uber started).

If you think of Uber as absorbing the taxi markets, it gets pretty huge.

[…]

If you think of Uber as a giant supercomputer orchestrating the delivery of millions of people and items all over the world (the Cisco of the physical world), you get what could be one of the largest companies in the world.

Good companies always seem to be playing a different game than you think they are…outsiders see only the tactics and not the strategy. And the best ones succeed.

Here’s an interesting little tidbit from the Economist about Uber…drivers rate their passengers.

At the completion of a trip, a passenger is asked to rate the driver; the driver, in turn, rates the passenger. Drivers who have poor ratings do not last long, Mr Kalanick says, while poorly-behaved passengers may have trouble securing a ride, since a driver can decline a fare if the hailer has a bad reputation.

I’d expect more of this credit scoring in the future…you might have trouble getting a reservation, a hotel room, or seat on a plane if you’re an asshole.

I went a’dancin’ last night. Beat Radio is going off the air so they threw a little party at First Ave last night called “Beatoff”. It was fun…for the most part…it was a little annoying because of the nature of the crowd. Usually, a techno show at First Ave means a techno crowd; a crowd that comes to dance and experience the event instead of scoping for that night’s lay or getting drunk. Instead, last night’s crowd was very much the typical bar crowd. Sigh. Don’t get me wrong, the music was good (most of the time) and I had fun dancing, but it just wasn’t the most ideal atmosphere to deal with when all I really wanted to do was dance.

Socials & More