The Williamsburg Bridge Riders

Adam DiCarlo takes photos of commuters (mostly bikers) as they exit the Williamsburg Bridge bike path on the Manhattan side and posts them to his Instagram account. (via @BAMstutz)

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

Adam DiCarlo takes photos of commuters (mostly bikers) as they exit the Williamsburg Bridge bike path on the Manhattan side and posts them to his Instagram account. (via @BAMstutz)

Photographer Ryan Weideman worked as a NYC taxi driver for 35 years (1981-2016) and photographed his passengers while on the job.

Huck did a profile of Weideman and his work several years ago.

“I drove a Checker cab but I usually got the wrecks because I only drove three or four nights a week,” he remembers wistfully. “I spent the rest of the time in my darkroom, printing and developing film.”

The quintessential New York cabbie, with a wisecracking mouth and lead foot on the gas pedal, Weideman carefully covered the first three letters of his license so that only the letters ‘DEMAN’ were visible. When passengers entered the cab, he would proudly announce, “You’re riding with the Street Demon.”

“I was on the edge of my seat most of the time because I was caught up in the rush of the ride,” he recalls. Although the 12-hour shifts were grueling, he never drank coffee or took drugs.

“It was all the adrenalin that flowed from my driving style. I enjoyed the thrill of driving and the sense of competitiveness. Some people really loved it; others were scared and wanted out so I would have to drop them off. Once in a while I would have a passenger that really enjoyed it. One guy jumped out of the cab and said, ‘My God, that was a religious experience!’”

Noah Kalina on viewing old photos or videos of yourself:

I think that’s why it’s so uncomfortable for some people to watch old videos of themselves. It exposes the core of who you really are.

No matter what you try to do, no matter where you end up going, no matter how much you might try to change, you are who you are, and that very particular and unique type of personality you have stays with you forever.

It’s fascinating, painful, revelatory, and embarrassing.

The photo above is my 6th grade school picture from 1984. I loved that velour vest for reasons I cannot presently fathom. When I think about who that kid was and who I am now, I hope that I’ve retained the best parts and let go of the things that didn’t serve him so well. It’s a process…

Counterpoint (or perhaps complementary point): I think often of this old post from The Sartorialist about a woman who reinvented herself upon moving to New York:

Actually the line that I think was the most telling but that she said like a throw-away qualifier was “I didn’t know anyone in New York when I moved here….”

I think that is such a huge factor. To move to a city where you are not afraid to try something new because all the people that labeled who THEY think you are (parents, childhood friends) are not their to say “that’s not you” or “you’ve changed”. Well, maybe that person didn’t change but finally became who they really are. I totally relate to this as a fellow Midwesterner even though my changes were not as quick or as dramatic.

Ooops, guess we’re doing two tonight. Goodness. Compare this to the video from last night. Tyshawn Jones is just getting so much speed up for these tricks. It’s like a different sport. Both so great to watch.

Saw a quote from Tyshawn Jones where he said he grew up watching this Andrew Reynolds - Baker 3 video and you can see the similarities in the size/speed of the tricks. (Frontside flips at :30 and 4:45ish, hooo boy.)

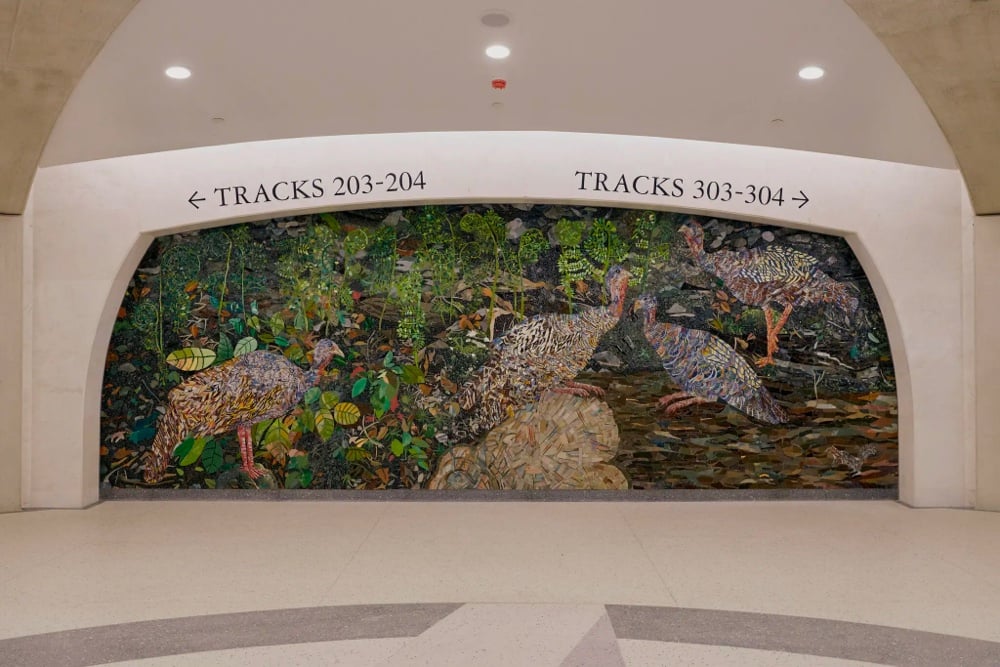

From The Monacelli Press, Contemporary Art Underground: MTA Arts & Design New York is a forthcoming book about the art projects the MTA has completed in the last decade in the NYC transit system.

Of special interest is the discussion of fabricating and transposing the artist’s rendering or model into mosaic, glass, or metal, the materials that can survive in the transit environment.

Nancy Blum’s piece at the 28th Street station (top, above) is my favorite piece in the entire subway system; I love it so much. (via colossal)

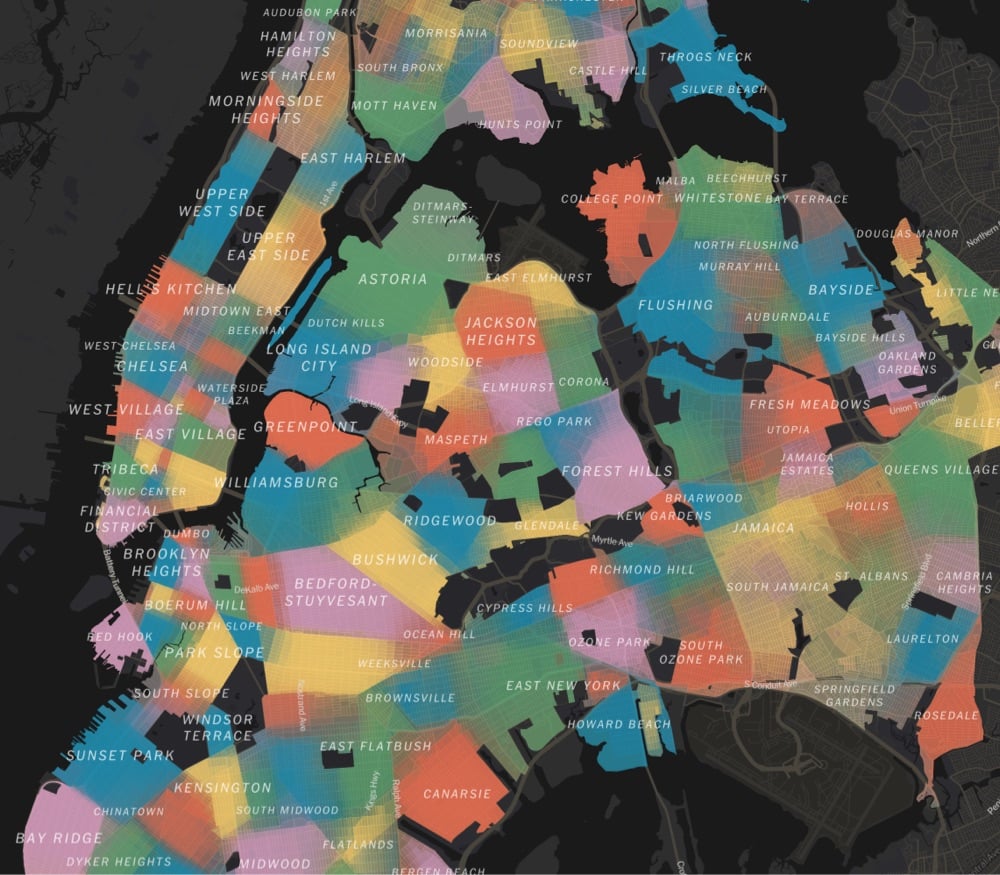

Using survey data, responses from community boards & city council members, and over 37,000 responses from NYC residents, a team at the NY Times has made a detailed map of the 350+ distinct neighborhoods in NYC. From a companion article:

It’s a New York pastime to gripe that neighborhoods are invented and defined by real estate brokers, developers and other city gatekeepers. But the more interesting truth may be that they are also reinvented and reinforced, refracted through race and class, by us: by the air traffic controller who lives in Little Yemen, by the Manhattan community manager who’s sure his constituents live in East Harlem — and not “Upper Carnegie Hill” — and by the Brooklyn residents who decided to name a relatively flat piece of land Boerum Hill.

A name has power. It can foreshadow who will be moving in. By itself, it can conjure so much: gentrification, displacement, inequality, status. When we argue over names, or even invent new ones, we may be trying to exert some of that power — or lamenting that others have more power than we do.

We asked New Yorkers themselves to map their neighborhoods and to tell us what they call them. The result, while imperfect, is probably the most detailed map of the city’s neighborhoods ever compiled.

The article is interesting throughout:

Our map reveals two main kinds of divisions: sharp ones and fuzzy ones.

The fuzzy ones often reflect areas in transition or dispute, where there’s no consensus or where gentrification is rewriting boundaries in real time.

The sharp ones often reflect features of the landscape itself: wide avenues, highways, remnants of canals. When you cross the street, you know you’re in another neighborhood.

Next time I’m in NYC, I’m definitely going to Little Yemen for lunch.

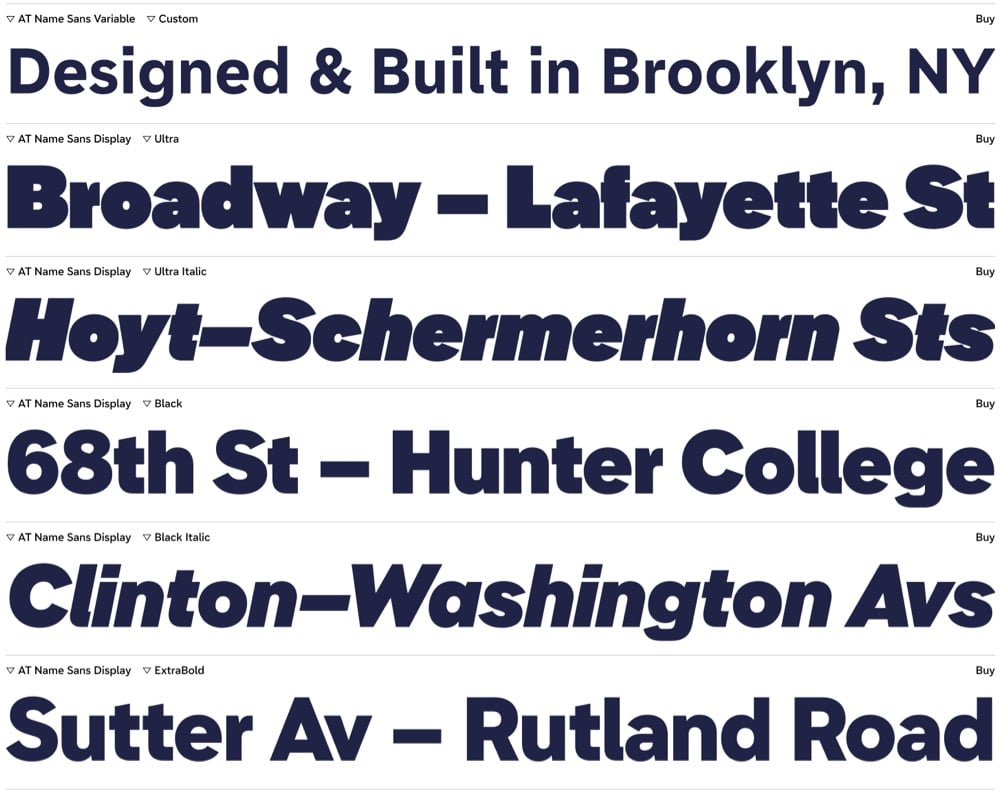

Name Sans is a typeface based on the tile mosaic lettering found in NYC subway stations.

The architects and craftworkers who designed & laid these tiles used a letter construction that was part geometric and part grotesque, with typographic optical corrections often either exaggerated or totally missing. Name Sans interprets these ideas into an extensive type system that is at once anonymous and full of personality, useful for everything from branding to wayfinding to digital interfaces.

Lovely. I like this a lot.

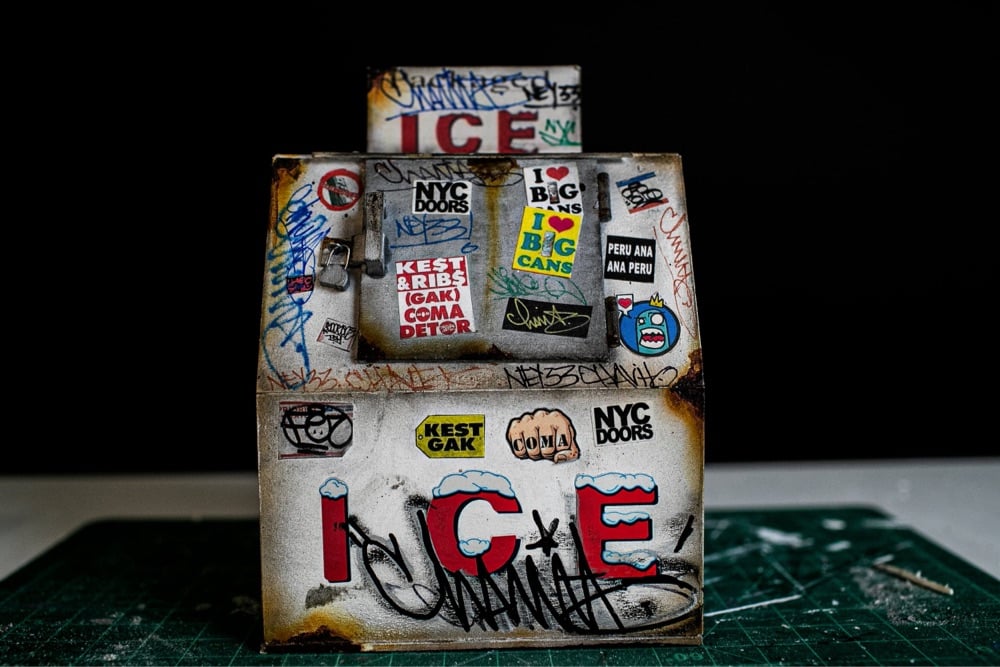

Danny Cortes took up making patinated miniatures of familiar NYC objects during the pandemic and it turned into a full-time vocation for him. He spoke to the NY Times about how his work puts him in the flow state:

“I loved that when I worked on a piece, I didn’t think about my problems — my divorce, the pandemic,” said Mr. Cortes. “It was an escape — like I’m meditating, literally floating. I didn’t have a problem in the world. I wanted that high again, I kept chasing that.”

Love that and love the miniatures…they are crazy realistic.

Blighted façades and distressed structures are the very scenes which fuel Daniel’s attention to detail. The work to produce each piece is arduous and requires great precision to achieve such realism. Daniel had developed techniques that can give a model an aged, distressed or patinated style. He also recreates miniature scaled vintage advertising posters and graffiti art on his models. Daniel’s miniature models make unique collectable creations that will take you on a gritty romantic journey through New York that everyday passers by have overlooked.

You can check out more of Cortes’ work on Instagram.

Somehow I’d never heard of this before watching this video (nor it seems, had much of anyone else outside of the participants), but the building located at 368 Broadway in Manhattan was, in the years after 9/11, the creative home for a surprising number of filmmakers: Greta Gerwig, Lena Dunham, the Safdie brothers (Josh & Benny), the Neistat brothers (Casey & Van), the Schulman brothers (Ariel & Nev), and Henry Joost.

Here’s a clip of Van Neistat talking about those days (starting at 19:50):

Brian Eno had a word for places like 368 Broadway and the people who gather together to create: scenius. Austin Kleon elaborated on scenius in his book Show Your Work:

There’s a healthier way of thinking about creativity that the musician Brian Eno refers to as “scenius.” Under this model, great ideas are often birthed by a group of creative individuals — artists, curators, thinkers, theorists, and other tastemakers — who make up an “ecology of talent.” If you look back closely at history, many of the people who we think of as lone geniuses were actually part of “a whole scene of people who were supporting each other, looking at each other’s work, copying from each other, stealing ideas, and contributing ideas.” Scenius doesn’t take away from the achievements of those great individuals: it just acknowledges that good work isn’t created in a vacuum, and that creativity is always, in some sense, a collaboration, the result of a mind connected to other minds.

Stephanie Shih is a Brooklyn-based ceramic artist who makes painted sculptures of ordinary objects like food, shoes, hats, and signs. A recent exhibition focused on the overlap of immigrant communities of Asians and Jews on NYC’s Lower East Side and Chinatown.

A few yards from where the Bernstein-on-Essex sign hangs is a long table that displays Shih’s sculpted takes on other iconic food and drink, like a bilingual bottle of Soy Vay Veri Veri Teriyaki, roast pork on garlic bread, Golden Plum Chinkiang Vinegar, and a can of Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray Soda.

“A lot of my solo shows are about this idea of authenticity,” says Shih, who has been working in ceramic full-time since 2015. “There are no cultures that are untouched by other cultures. These are two communities that grew up alongside each other. It was not always friendly, but simply from proximity and the fact that they were the two largest non-Christian immigrant groups, they had commonalities.” For example, she says, the tradition of Jews eating Chinese food on Christmas began right near Harkawik, on the Lower East Side.

You can find much more of her work on Instagram.

From the Library of Congress, footage of the first gay pride march in NYC in 1970. The march, called the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, was held on June 28 to commemorate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. From Gothamist:

The Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day March started in Greenwich Village at about 2 p.m. that day in 1970, just outside the Stonewall Inn, which was then for rent, having closed the previous October.

As they gathered, the marchers were few, and brave. There were groups from Washington, DC and Boston, college organizations from Rutgers, Yale and Columbia. Some transgender people who were there at the time said that organizers asked them to march in the back, but they refused.

“The trans community said, ‘Hell no, we won’t go.’ We fought for this as much as you did, or even started it,” said Victoria Cruz. “And we just mingled throughout the crowd. There was no trans contingent. We just mingled.”

They started walking very briskly up Christopher Street, because they were scared. There had been bomb threats. People worried they would be shot at, or harassed again by the police. Martin Boyce was there, and he says that afterwards they joked it was “the first run.”

“I was worried about being single file, because I just watched a program on National Geographic about wildebeests and I saw how the ones on the side were picked off. So I thought I would stay in the middle — but there was no middle.”

As the march went on, it gathered people & momentum and they eventually made it without major incident to Central Park.

This is a sweet video profile of La Dinastia, one of the last old-school, family-run places in NYC where you can find Chino-Latino cuisine. From Lisa Chiu at ThoughtCo, a brief history of Asian-Latin food blends:

Cuban-Chinese Cuisine is the traditional fusing of Cuban and Chinese food by Chinese migrants to Cuba in the 1850s. Brought to Cuba as laborers, these migrants and their Cuban-Chinese progeny developed a cuisine that blended Chinese and Caribbean flavors.

After the Cuban Revolution in 1959, many Cuban Chinese left the island and some established Cuban Chinese food restaurants in the United States, mainly in New York City and Miami. Some diners contend that Cuban-Chinese food is more Cuban than Chinese.

There are also other genres of Chinese-Latin and Asian-Latin food blends created by Asian migrants to Latin America over the last two centuries.

See also Chinese Latinos Explain Chino-Latino Food and from The Village Voice in 2014, The Definitive Guide to NYC’s Chinese-Latin American Restaurants, many of which, like La Dinastia, are still around.

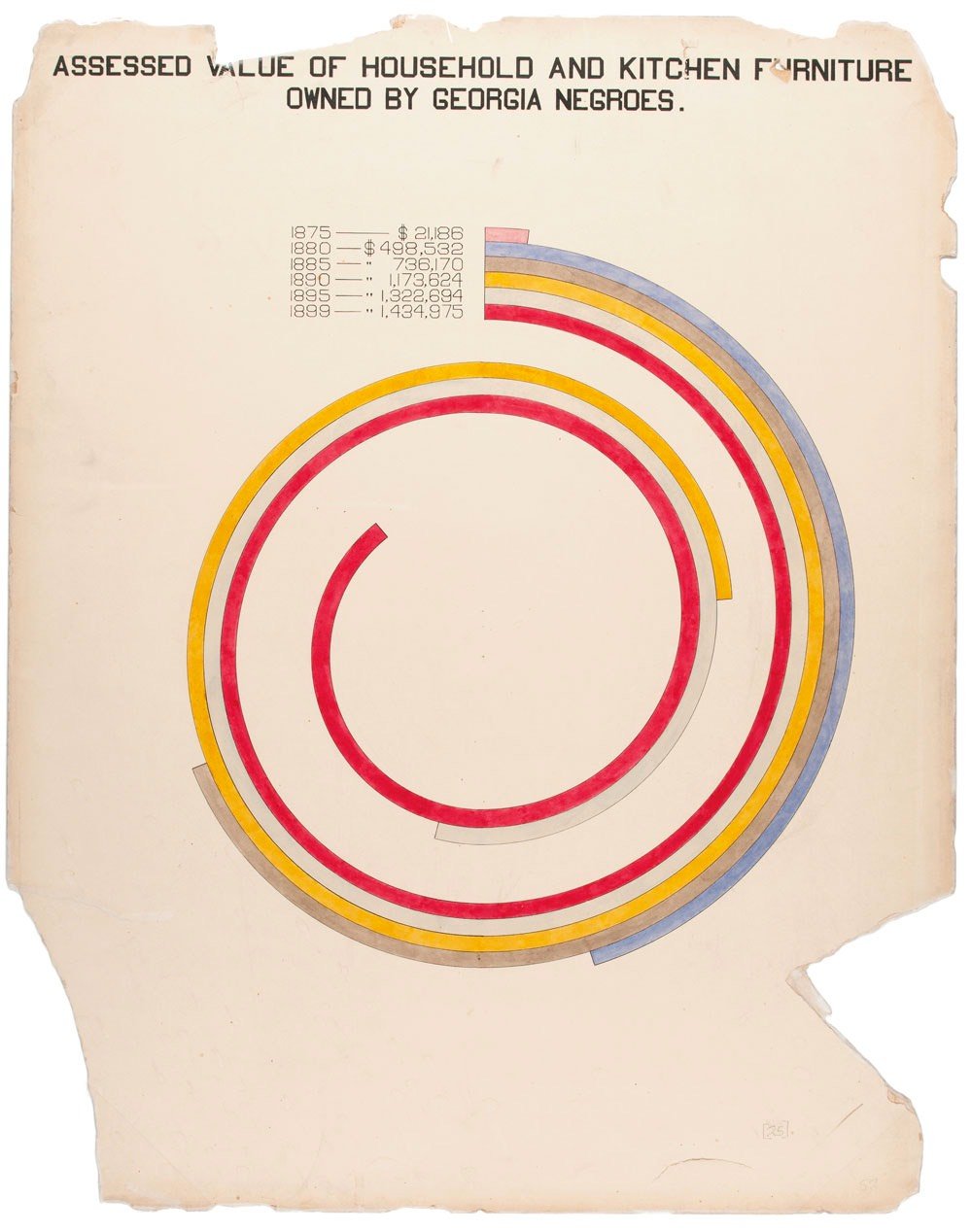

I’ve written before about the data visualizations created by W.E.B. Du Bois for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Apparently a selection of these infographics are on display at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in NYC until May 29.

Wish I could get down there to see these…

Starting last May and continuing through at least January of this year, Joshua Spodek has cut the ultimate cord: living off of the electrical grid in perhaps the most electrically connected place in the United States: Manhattan. Spodek wrote a fascinating article about his experiment in urban off-the-grid living for Ars Technica.

Some changes that made the experiment work included reading more books, writing by hand, choosing salads over cooked foods, going out instead of staying in, and shifting work to daytime hours. At first, I considered these changes sacrifices, but looking back, I view them more as a cultural shift, a bit like when I lived overseas and couldn’t find a good bagel. Finding the local equivalent-croissants in Paris or vegetable steamed buns in Shanghai-worked better than complaining, and it expanded my world.

Whenever I was tempted to lament the sacrifices I was making, I reminded myself that people have been living in Manhattan for around 10,000 years — technology shouldn’t make me less able or resilient than them.

The one thing I couldn’t sacrifice was my pressure cooker, which was the most efficient way to cook (and my greatest single consumer of energy). A full battery charge would power the cooker to make stew good for five meals and still leave a couple of hours’ charge for my computer and phone. I used almost no other appliances. I began waking up with the sun at 5 am to avoid needing lights. My battery has a one-watt LED that sufficed for cooking and eating, so I haven’t used my floor lamp.

There are some cheats and caveats (like, it’s impossible to live in Manhattan without indirectly benefiting from all the generated energy around you) but what an intriguing experiment. (via @irwin)

After leaving a job at The New Yorker in the wake of his older brother’s death, Patrick Bringley spent 10 years working as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC. He wrote a book about his experience at the museum, All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me (ebook). From a review at NPR:

In the wake of his 27-year-old brother Tom’s death from cancer in 2008, Bringley, two years his junior, gave up a prestigious “high-flying desk job” at The New Yorker, where “they told me I was ‘going places,’” for a job in which “I was happy to be going nowhere.” He explains, “I had lost someone. I did not wish to move on from that. In a sense I didn’t wish to move at all.”

Drawn to “the most straightforward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew” — a job that promised room to grieve and reflect in the wake of his loss — Bringley arrived at the Met in the fall of 2008. He explains his state of mind when he pivoted toward this union position for which he donned a cheap, blue, polyester uniform and received an allowance of $80 a year for socks: “My heart is full, my heart is breaking, and I badly want to stand still a while,” he writes.

From a piece in the New Yorker in which Bringley tours his old stomping grounds:

He answered an ad in the Times and went to an open house. “They tell you the hours” — for beginners, twelve hours on Fridays and Saturdays and eight hours on Sundays — “and half the people leave,” he recalled. After a week of training (“Protect life and property, in that order,” he was told), he joined the Met’s largest department: some five hundred guards, who work in rotating “platoons.” Bringley spent the next decade at the museum, and has now written a guard’s-eye memoir, “All the Beauty in the World,” detailing a job that is equal parts dreamy, dull, and pragmatic. “You can spend an hour deciding to learn about ancient Egypt, or look around at people and write a short story about one in your head,” he explained.

Bringley’s website has a page that lists all the art he mentions in the book, with links to each artwork on the Met’s website. I love this sort of thing from authors — it’s where I found the image at the top of the page: Titian’s Venus and Adonis. You can also book a tour of the museum with Bringley.

Eric Huang is the chef/owner/operator of Brooklyn’s lauded Pecking House fried chicken joint. In a recent Instagram post, Huang explains why tipping is a part of the experience at his restaurant.

We do NOT use a tip credit at Pecking House. If we do not take a tip credit that means we pay every employee at least $15/hour. We then pool the tips and divide them among the entire hourly staff, including all back-of-house employees. This helps to foster an equitable team culture where everyone feels they are participating in the restaurant’s success.

So far, we’ve been able to pay every front-line employee an average of an extra $7 per hour on top of their hourly wages. We’ve been managing that while collecting a tip average of 18% on a check average of $26. So even an entry-level employee at Pecking House is making $22/hour if not more.

Almost no one in New York City does this. This is pretty damn unique. And while people have been generally enthusiastic about supporting restaurants as they weather a furious storm of inflation, this is an easy way for us to take better care of our restaurant workers. Because the pandemic revealed quite painfully that we are a sizable, important and vulnerable population. And this is all perhaps even more relevant given that certain Best Restaurants have been outed about certain abhorrent business practices. Their example should be motivating us to take a look at how we can change the restaurant industry for the better.

So when you add a tip at Pecking House, you’re really helping to take care of the whole team and acknowledge their effort in creating your experience. I think we’ve all been guilty of having a great time and leaving a fat tip, but forgetting at that moment that the cook who made you that taglioni isn’t seeing an extra penny. So for those of you who have been helping us out with 18% on $26, an extra $4, know that it’s going to everyone. Except and rightfully so, the chef standing there pointing at stuff, not being terribly helpful, i.e. me.

From there, he goes on to explain why eliminating tipping doesn’t work from the standpoint of the restaurant (customers spend less), its employees (they make less than they could elsewhere), or, surprisingly, its customers (they want the illusion of control/agency). And there’s also a sort of tacit collusion that happens amongst restaurants — no one wants to eliminate this obviously unfair system because of the financial hit so none of them do. The whole thing is worth a read.

Back when I lived in NYC, a restaurant I frequented experimented for a few months with eliminating tipping. In practice, it meant that the bartenders and servers made less money and the chefs got paid more. As a regular customer who knew and liked everyone who worked there, I thought that was much more fair than front-of-the-house staff being paid more than the kitchen folks due to some antiquated racist bullshit. In the end, they had to revert to doing tips again because customers weren’t spending as much money and it eliminated the restaurant’s profit margin. Customers looked at the higher prices ($25 for the chicken instead of $21, $17 cocktails instead of $14) and ordered fewer and less-expensive items, even though they were paying exactly the same amount for them by tacking 20% onto the check at meal’s end. It’s just economic reality: lower posted prices with added fees will encourage people to spend more money because the posted price is what gets stuck in their heads.

It seems like the only way to get rid of tipping in the US is for every restaurant to do it simultaneously, either by mutual decision (ha!) or through some kind of legislation (double ha!). But because of the pandemic and the ubiquity of digital payment screens, tipping is more engrained in American commerce than ever so…??

See also The Failure of the Great Tip-Free Restaurant Experiment.

For 10 years beginning in the late 90s, photographer Angela Cappetta captured the goings-on of a multi-generational Puerto Rican family living on NYC’s Lower East Side, focusing particularly on the youngest daughter, Glendalis. From a recent piece in the New Yorker by Ana Karina Zatarain:

The neighborhood was different then. During those years, just before a fierce wave of gentrification hit the area, the photographer Angela Cappetta often rose at dawn to roam the streets, a Fuji 6x9 camera in hand. (“I still use it,” she told me. “It looks fake, like a toy.”) It was on one of those mornings that Cappetta encountered a clan that reminded her of her own upbringing, within a multigenerational family of Italian immigrants, in Connecticut. As a child, Cappetta was shepherded among various homes by aunts, uncles, and older cousins-a constant and frenetic flow of relatives. The family she met that day, Puerto Rican New Yorkers living on multiple floors of a tenement building on Stanton Street, had a similar dynamic. Instinctively, she began placing each member in their role. “I looked at this beatific, beautiful family, and I thought, Yeah, I relate to this,” she recalled.

This is delightful: a group of five friends who grew up on a predominantly Italian block of Union St. in Brooklyn reminisce about their childhood and the neighborhood in this animated video.

Imagine a whole block where 75-80% of the kids spoke Italian. We all lived there.

A lot of families were first generation Italians in America. Everybody was poor.

It was an open concept where, in the evening, the mothers and the grandmothers would take their chairs, sit outside, while we’re playing in the street. People were out the window watching their kids from the fourth floor. It was tight-knit.

And whenever a stranger walked on the block, like the whole block knew that there was a stranger on the block. That’s how tight-knit it was.

We’ve been together since, forget about it, since we were infants. Like brothers. Paisanos.

The names of the games they played in the street are amazing; I’ve only actually heard of a couple of these: stoopball, cracktop, red light green light one-two-three, ringolevio, buck buck, old mother witch, slapball, skelsies, boxball, stick ball, and hot peas & butter. The rules for hot peas & butter, which Eddie Murphy remembers playing as a kid:

It involved a long leather belt with a sharp edge. As kids gathered on the stoop or base, one person was selected from the group to hide the belt in our community’s parking lot. The belt was usually tucked away in a car bumper or under a loose hubcap or something.

After hiding it, the child returned to base and said, “Hot peas and butter, come and get your supper!” With that call, dozens of eager children ventured out to find the belt. The person who hid it constantly screamed who’s “hot” or near the belt and who’s “cold” or far away from it. This could go on for 15 even 20 minutes, and then the climax! The person who located the belt got to whip and thrash every child until they ran hurriedly back to base.

When I was a kid, we played a game with a homophobic name where one kid would have the football and the rest of us would try to take it from them using any means necessary; it was a violent version of keep-away. Being a small bookish sort, I don’t think I ever got the football and if I did, I threw it down the second anyone got close.

Anyway, back to the video…it’s really charming; here’s how it was produced.

The result is a vivid film that plays out on an intricately detailed model of a single block of brownstone Brooklyn. The childhood friends, now in late middle age, remember not just the games they played but also the prevalence of organized crime that shaped the neighborhood, and, to some degree, their own lives. And they talk, of course, about how the neighborhood has changed, laughing about the influx of “yuppies” who don’t return hellos on the street.

A short animated film about photographer David Godlis, who documented the glory days of CBGB, ground zero for the punk & new wave scene in the late 1970s.

Between 1976 and 1980, young Manhattan photographer David Godlis documented the nightly goings-on at the Bowery’s legendary CBGB, “the undisputed birthplace of punk rock,” with a vividly distinctive style of night photography.

You can check out some of Godlis’s photos on his website. (via open culture)

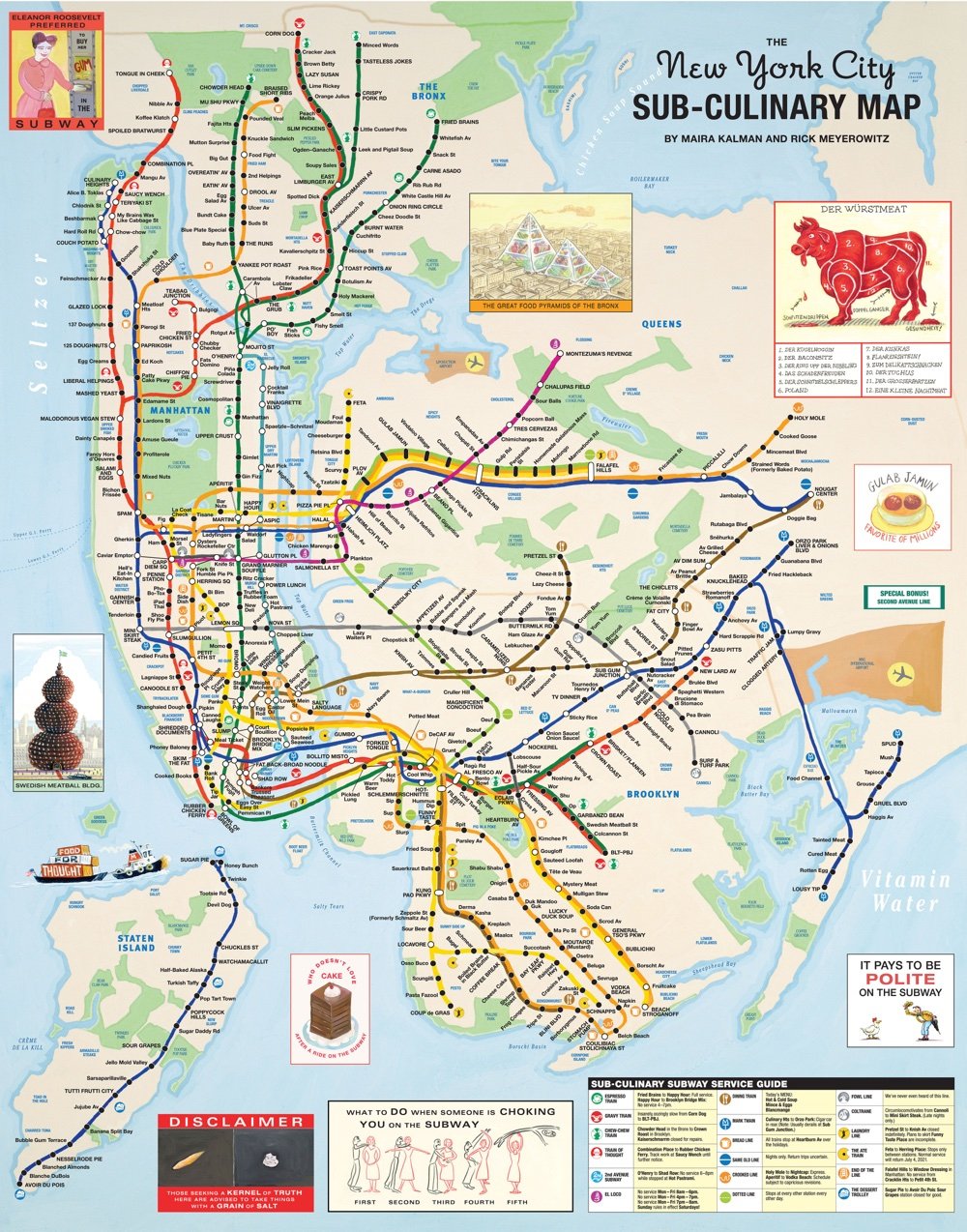

In the early 2000s, Rick Meyerowitz and Maira Kalman made a version of the NYC subway map where names of all the stations and landmarks were replaced with food. Here’s a detailed view of lower Manhattan and part of Brooklyn:

See also Simon Patterson’s The Great Bear and the City of Women NYC subway map.

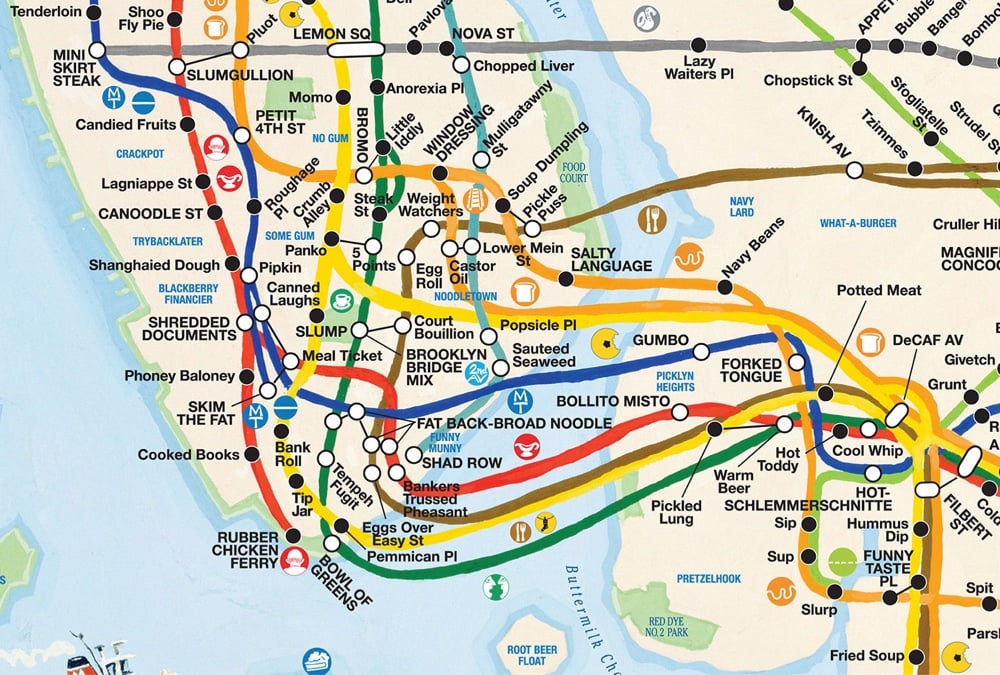

Dang, look at these new mosaics by Kiki Smith and Yayoi Kusama for Grand Central Madison, the MTA’s newest LIRR station.

As a former (and future?) New Yorker, I know a lot of the city’s dwellers appreciate the MTA’s commitment to public art and to mosaics in particular. Like the Dude’s rug, it really ties the city together.

In this video, using before-and-after satellite imagery, Claire Weisz of WXY, an architecture and urban design firm, explains how her company helped redesign three of NYC’s unruliest intersections: Astor Place, Cooper Union, and Albee Square. Unsurprisingly, the redesigns all involved taking space away from cars and giving it to larger sidewalks and more green space, to benefit people other than drivers.

Anne Kadet interviewed some chess hustlers in Washington Square Park about their chess work in the park and what they’ve learned about life playing chess.

If you want a game, I say one game, five dollars, five minutes. So we play a five-minute game for five dollars. If you said you don’t want no clock, I might say I give you one game, $10, because without the clock, it’s longer. You’re wasting time.

Some people say $5 to the winner. That means, we play each other and whoever wins gets the $5. That’s tricky, because I don’t know how strong you are. You might beat me and I lose $5. I’ve wasted time AND I’ve lost money! So I’m one of those people who don’t say $5 to the winner.

I’ll give you a lesson, a half hour for $20. I have some children that come just to see me once a week and I give them a lesson — $20 for a half hour. And there’s a lot of NYU students that come by, we give them a discount for being students. One hour for 40 bucks.

Marcel A. offered this advice that applies to nearly any situation:

The one thing I tell my students is that when you get to a confrontation of any type, you have to remain calm. When you remain calm, you can see the board a lot clearer. You can see the person you’re playing or arguing with a lot more clearly, for who and what they are. So you don’t even have to entertain that shit. You understand?

Nathaniel W. shares what he’s learned about people:

They timid, they’re not willing to take a chance. See this? [He moves a pawn forward one space.] That means sometimes people don’t want to be hurt. They have a fear of losing.

And E.G.G.S. offers perhaps the wisest advice of all:

I’m stuck right now. I can’t give any life advice.

The whole thing is worth a read.

See also The Last Chess Shop in NYC. (via fave 5)

Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure is a new exhibition of the life and work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, curated by his two younger sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux. It opened this past weekend in NYC and includes a bunch of work that’s never been exhibited before. From the NY Times:

The show, “Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure,” features more than 200 artworks and artifacts from the artist’s estate — 177 of which have never been exhibited before — in a 15,000-square-foot space designed by the architect David Adjaye. Providing perhaps the most detailed personal portrait to date of Basquiat’s development, the show comes at a time when the artist’s market value continues to soar and his themes of race and self-identity have become especially resonant. (The mayor’s office is to proclaim Saturday, the show’s opening, Jean-Michel Basquiat Day.)

“They’re literally opening up the vaults,” said Brett Gorvy, a dealer and a former chairman and international head of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s. “These are paintings I’ve only seen in books.”

This looks great; definitely hitting this the next time I’m in NYC. Tickets are available here. (via pentagram, who did the identity for the exhibition)

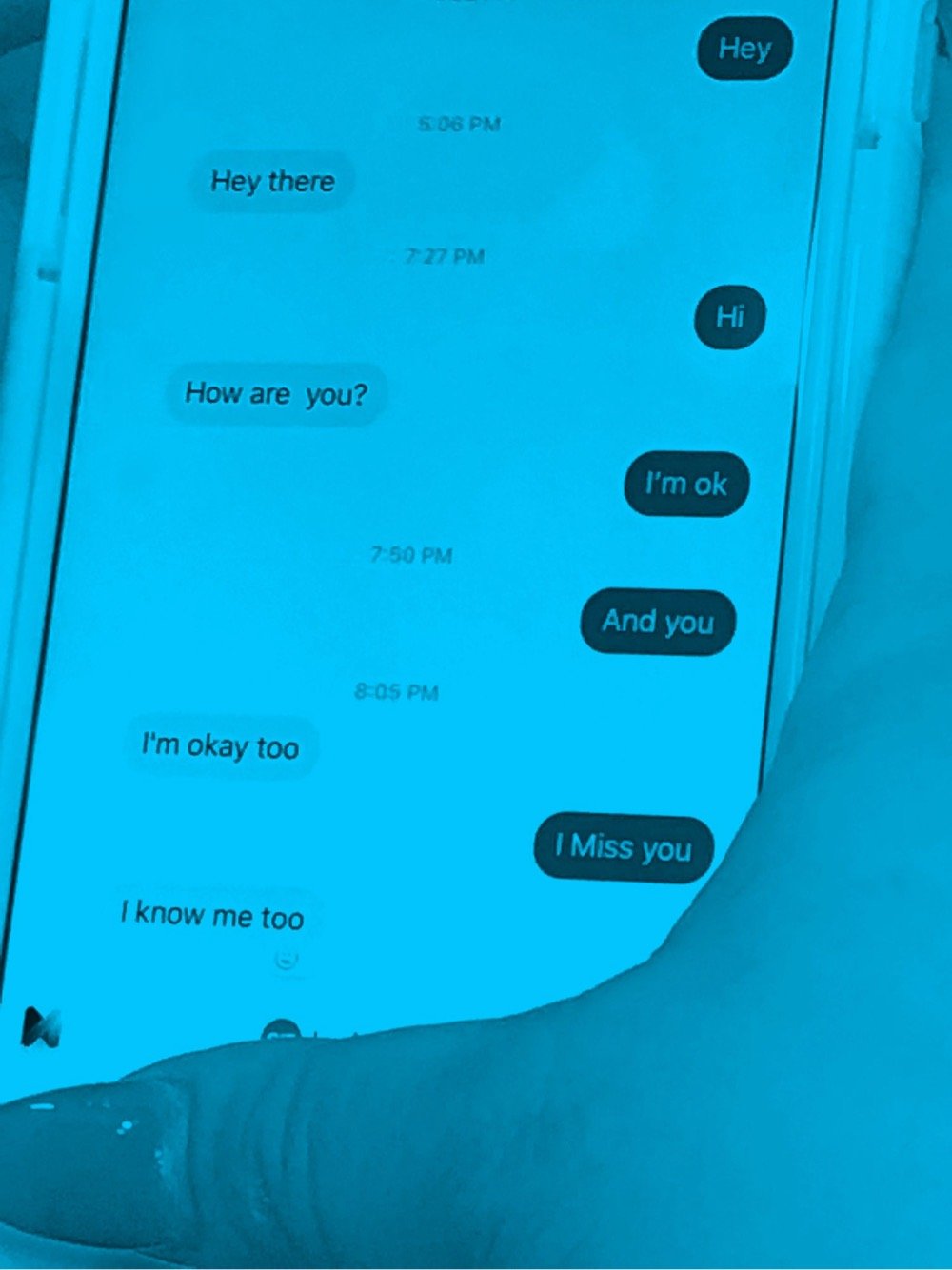

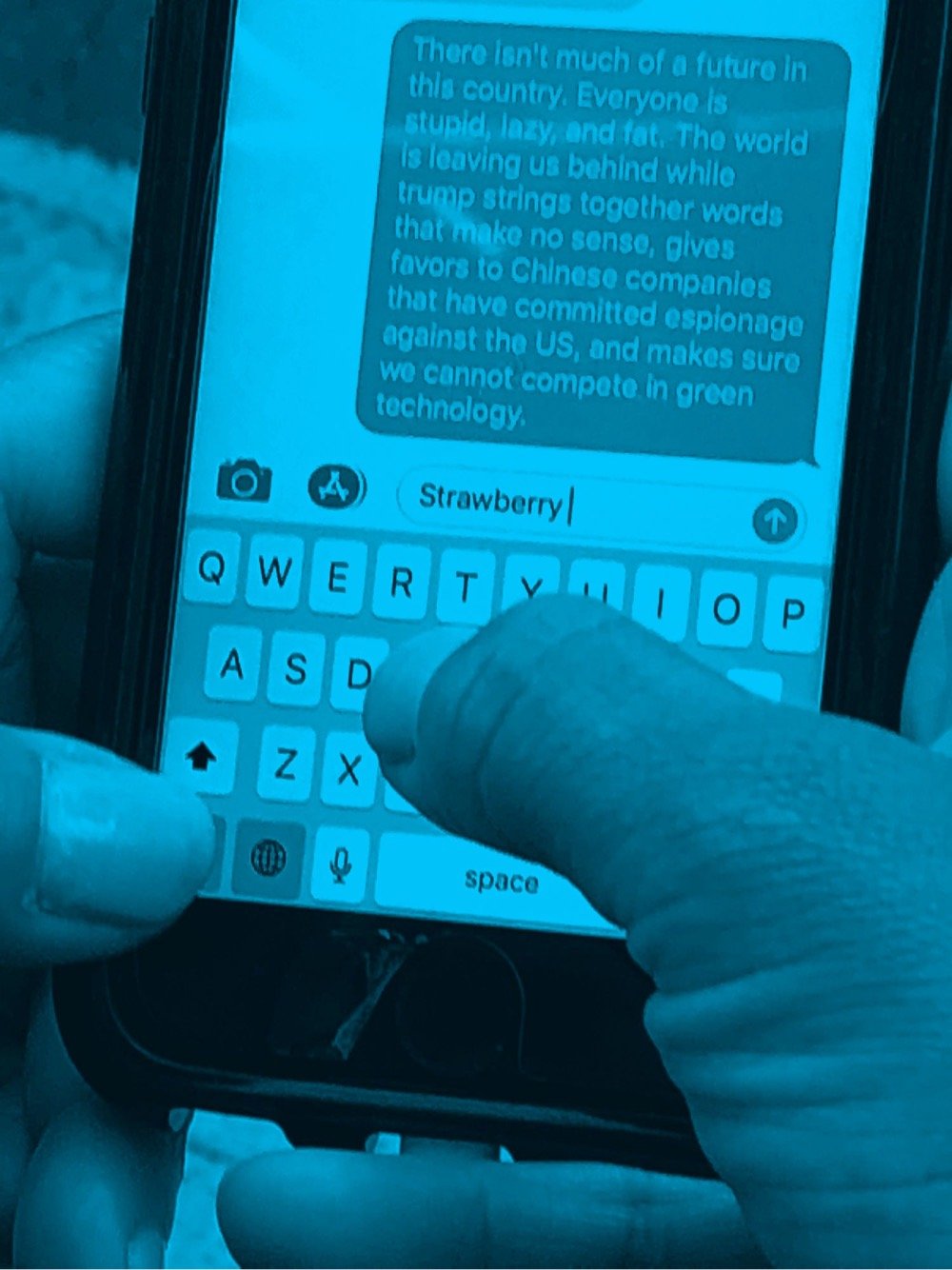

#nyc is photographer Jeff Mermelstein’s collection of photos he’s taken on the streets of NYC of text messages on people’s phone screens. From a review of the book at LensCulture:

At once detached and intimate, we are offered a collection of fragmentary texts that register the daily life events and feelings of a city’s occupants, a raw vox pop assortment of broken and interrupted and incomplete messages. We watch users reading, texting and even editing on their phones. There are texts about break ups, declarations of love, dreams, lusts, illnesses, affairs, abortion, pregnancy, death, sexual proclivities, money, as well as recipes, cooking, dirty shower curtains and roach traps. Some messages remain unfathomable and enigmatic: “The nun said, ‘That’s OK…”

I wonder about the privacy aspect of this, but it’s always fascinating to see how other people communicate.

Ahh, the 80s — when children were given much more freedom than today, an autonomy that two Irish boys used in 1985 to travel from their house in a Dublin suburb all the way to New York City — via two trains, a ferry, and then stowing away on a JFK-bound 747, with nothing more than a few coins in their pockets.

When the boys arrived at John F. Kennedy International Airport, in New York, they tried to bypass a security checkpoint with a sly bit of street smarts, saying to the officer, “Our ma’s just behind us.” It aroused suspicion, but the pair ran when the airport official turned his head away. They then spent a few hours in the airport before wandering outside, astounded by yellow cabs and lofty skyscrapers. A policeman, Kenneth White, stopped them and asked where they were headed. After they lied to White about how they were meeting their mother at the center of town, White pressed further, and Byrne and Murray admitted that they were alone. White radioed for a supervisor, and Sergeant Carl Harrison came to assist him. After more questioning, the two boys were placed in the back of an N.Y.P.D. car and driven to a precinct, where they were held in a room for several hours — they eventually confessed what they had done. After calling other overseas jurisdictions and the boys’ parents, the police officers fed the boys chips and soda, and unloaded their own guns and let the boys play with the firearms. Air India put Byrne and Murray up in a gigantic suite at a five-star hotel and plied them with McDonald’s and movies. “I was never in a hotel before, so it was brilliant,” Murray says. The next day, the security guards who were tasked with supervising the boys asked them why they had come. Byrne and Murray told the officials that they wanted to meet the character B. A. Baracus from “The A-Team.” The guards then brought the boys on sightseeing tours throughout the boroughs, gave them some cash, and bought them “I Love New York” T-shirts.

What a story! It’s wonderful to hear the two men talk about their now long-ago adventures with a mischievous twinkle in their eye — and the old footage of Dublin, Heathrow, and NYC is a great accompaniment.

Stay Connected