How to design a movie poster

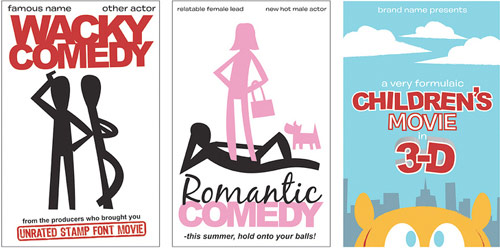

Travis Pitts outlines the six rules of modern movie poster design. Here are three examples:

Best viewed large for easy reading of fine print.

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

Travis Pitts outlines the six rules of modern movie poster design. Here are three examples:

Best viewed large for easy reading of fine print.

The Society for News Design recently posted their picks for the best designed newspapers in the world.

Speaking of Apple, here’s a profile of Jerry Manock, who worked for Apple from 1977 to 1984 and designed the case for the Apple II and helped design the Macintosh. Manock was Jobs’ first Jony Ive.

The whole basis of the class I’ve taught at UVM for 21 years is … integrated product development, which means concurrently looking at all of these things: the aesthetics, the engineering, the marketing … which is what we were doing at Apple. Not necessarily purposefully, but everybody was just thrown together… I would walk through the software place and look around and see what people were doing … walk through the marketing area. I had my drawings all on the walls, so anybody could come up. There was a red pencil hanging there. I’d say, “If you see something you don’t like, or is a problem — I don’t care whether it’s a janitor or Steve — write the correction, circle it, put your phone there and I’ll call you and we’ll talk about it.”

(thx, mike)

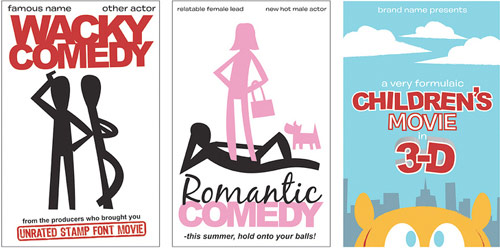

From MUBI notebook, a selection of great movies posters from 2011, including Chris Ware’s lovely one for Uncle Boonmee.

(via dooce)

I love the cover of the most recent Bloomberg Businessweek:

Here’s a peek at how the design process works at the magazine.

Designer Adam Ladd asked his five-year-old daughter for her impressions of several well-known logos. This is great:

(via stellar)

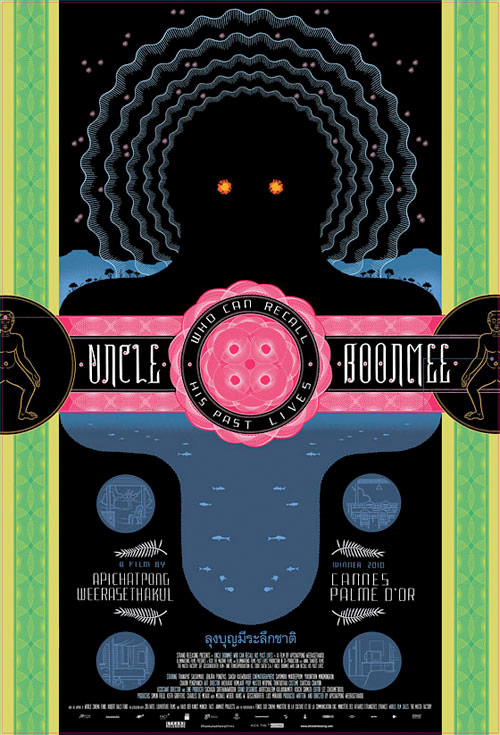

Posters for Oscar nominated movies that maybe tell the truth of each movie a bit more than the conventional posters. For instance, Iron Lady becomes Total Bitch, Tree of Life becomes Wuh?, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo becomes All the Rape, No Subtitles.

(via ★vuokko)

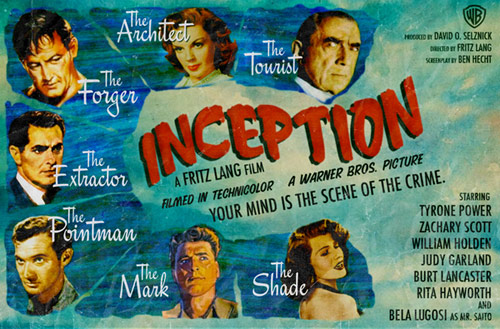

If recent movies like The Hangover, Drive, Inception, and Rushmore had been made in an earlier era, who would have starred in and directed these premakes? How about Dean Martin, Jack Lemmon, and Jerry Lewis in The Hangover?

Or Inception directed by Fritz Lang?

(thx, al)

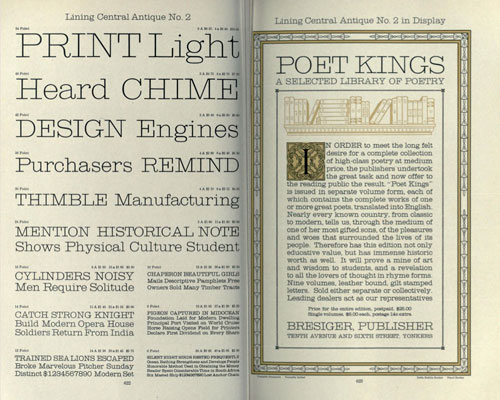

The Internet Archive is hosting a copy of the American Specimen Book of Type Styles put out by the American Type Founders Company in 1912. It’s a 1300-page book listing hundreds of typefaces and their possible use cases.

There’s also a 1910 copy of what is basically the German version of the ATF book. Look at these swirls! (via @h_fj)

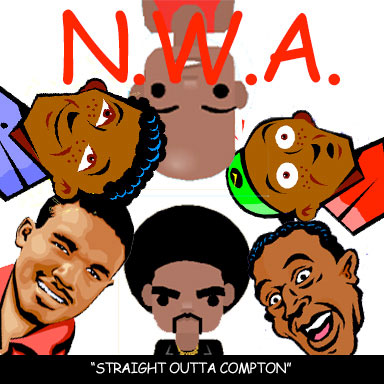

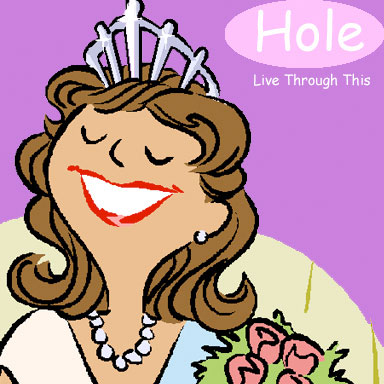

On the Clipart covers blog, you’ll find noted album covers redone with clip art and Comic Sans.

(via @aaroncoleman0)

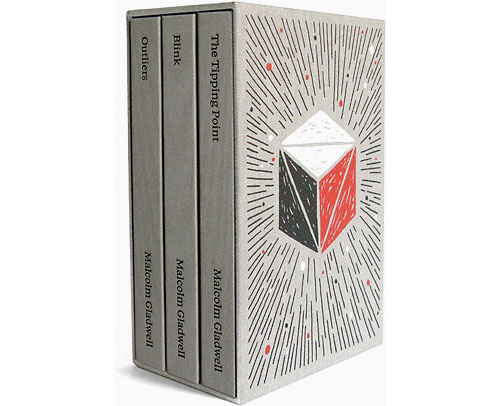

Paul Sahre and Brian Rea designed a 3-book boxed set for Malcolm Gladwell’s “intellectual adventure stories”.

“During our initial meeting with Malcolm, he referred to the three books as ‘intellectual adventure stories,’” Sahre tells Co.Design. “Brian and I really responded to that, as it suggested a specific and interesting way to think about how the books could be designed. We wanted the books to feel like first editions of Moby-Dick or Treasure Island or The Wizard of Oz.”

The tasteful gray cloth binding and foil stamping of the set and its “extremely conventional” design, as Sahre puts it (“maybe ‘comfortable’ would be a better way to describe it,” he adds) makes me think of famous children’s literature collections, like The Chronicles of Narnia. “This ‘traditional/comfortable’ design allowed for the drawings Brian was doing to venture off into the abstract and unconventional place they ended up,” Sahre continues. “More importantly, the quiet design allowed the text and the drawings room to interact and to breathe. I hope the reader doesn’t notice the design of the book at all.”

The set is available on Amazon.

This map of the US was made by David Imus — he worked seven days a week for two years on it — and it won the Best of Show award at the Cartography and Geographic Information Society competition for 2010. Here’s why.

According to independent cartographers I spoke with, the big mapmaking corporations of the world employ type-positioning software, placing their map labels (names of cities, rivers, etc.) according to an algorithm. For example, preferred placement for city labels is generally to the upper right of the dot that indicates location. But if this spot is already occupied — by the label for a river, say, or by a state boundary line — the city label might be shifted over a few millimeters. Sometimes a town might get deleted entirely in favor of a highway shield or a time zone marker. The result is a rough draft of label placement, still in need of human refinement. Post-computer editing decisions are frequently outsourced-sometimes to India, where teams of cheap workers will hunt for obvious errors and messy label overlaps. The overall goal is often a quick and dirty turnaround, with cost and speed trumping excellence and elegance.

By contrast, David Imus worked alone on his map seven days a week for two full years. Nearly 6,000 hours in total. It would be prohibitively expensive just to outsource that much work. But Imus — a 35-year veteran of cartography who’s designed every kind of map for every kind of client — did it all by himself. He used a computer (not a pencil and paper), but absolutely nothing was left to computer-assisted happenstance. Imus spent eons tweaking label positions. Slaving over font types, kerning, letter thicknesses. Scrutinizing levels of blackness. It’s the kind of personal cartographic touch you might only find these days on the hand-illustrated ski-trail maps available at posh mountain resorts.

Update: The map is now in its fourth version of the second edition, updated in Sept 2022. I updated the image above to a snippet of the newest map.

A lovely short film by Ben Proudfoot about a letterpress company and a paper company who are scraping by next door to each other in Los Angeles.

An excellent 26-minute talk by Jonathan Hoefler of the Hoefler & Frere-Jones about how they think about designing typefaces and webfonts in particular.

Today, as webfonts are buoyed by a wave of early-adopter enthusiasm, they’re marred by a similar unevenness in quality, and it’s not just a matter of browsers and rasterizers, or the eternal shortage of good fonts and preponderance of bad ones. There are compelling questions about what it means to be fitted to the technology, how foundries can offer designers an expressive medium (and readers a rich one), and what it means for typography to be visually, mechanically, and culturally appropriate to the web. This is an exploration of this side of web fonts, and a discussion of where the needs of designers meet the needs of readers.

I love Typekit, but I am very much looking forward to switching Stellar over to Whitney or somesuch when H&FJ’s webfonts are released (if the price and performance are right).

Oof…a wine by Roland Tissier has lorem ipsum on the label.

(via stellar)

Steve Silberman has a nice piece on Susan Kare, the woman who designed the original icons for the Macintosh, including a never-before-seen look at her initial sketches for some of them.

Inspired by the collaborative intelligence of her fellow software designers, Kare stayed on at Apple to craft the navigational elements for Mac’s GUI. Because an application for designing icons on screen hadn’t been coded yet, she went to the University Art supply store in Palo Alto and picked up a $2.50 sketchbook so she could begin playing around with forms and ideas. In the pages of this sketchbook, which hardly anyone but Kare has seen before now*, she created the casual prototypes of a new, radically user-friendly face of computing - each square of graph paper representing a pixel on the screen.

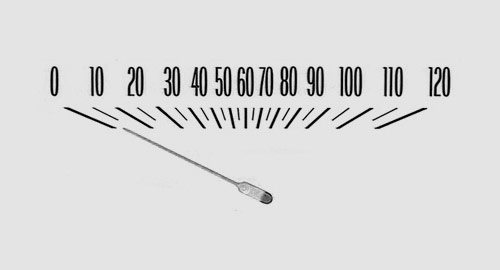

A collection of Chevy speedometer designs. My favorite is this one, from the 1970 Nova:

My dad had a bunch of different cars when I was growing up and I remember staring at this particular speedometer for hours…I loved the way the numbers scrunched together in the middle. (via ★vuokko)

Remember the kerning game? The same folks have built a letter shaping game where you can play at being a type designer. I found this to be a bit more difficult than kerning.

James Higgs wrote a provocative piece on something that I’ve noticed recently as well: the two sides to Apple’s design aesthetic. On the one hand:

[Apple’s] devices have become increasingly simple and pared down, even as the power contained in them has increased. There is very little, if anything, extraneous on the Magic Trackpad or the MacBook Air. And of course the iPhones 4 and 4S are radically simple, yet well-constructed masterpieces of industrial design.

Yet, when it comes to stuff that isn’t hardware:

But no one laughs when Apple delivers a calendar application for the iPad that tries its hardest to look like a real-word desktop calendar pad, complete with fake leather and “torn” pages.

Still fewer have a chuckle when they see the new Address Book app on Mac OS X Lion, or the even more recent Find My Friends iPhone app.

These apps, and many more besides, all stem from a completely different, and I would say opposite aesthetic sensibility than the plain devices they run on.

They are an expression of purest kitsch, sentimentality, and ornamentation for its own sake. In Milan Kundera’s brilliant definition, kitsch is “the absolute denial of shit”. These are Disney-like apps, sinister in their mendacity.

This isn’t a recent thing either…look at the cheeseball themes and transitions in Keynote (many of them used by Jobs in his keynotes), some of the default system fonts, the emphasis in past keynotes on things like Mail.app themes, etc. Without too much effort, you could pull together many design examples from their currently shipping software that make it appear as though Apple doesn’t have a good aesthetic sense of design at all. But then you look at the general aesthetics of OSX and iOS…I don’t know, it’s really confusing how the same company, especially one that had such strong design leadership, could produce something as beautifully spare as iOS and something as cheesy as the Game Center app. (via ★thefoxisblack)

After years of inactivity, K10k, the venerable design portal, has finally been permanently shuttered. Sad to see it go…K10k was one of a handfull of sites that most influenced my design/online efforts in the 90s.

MoMA is live-streaming the Talk to Me symposium all day today.

This evening and daylong program features presentations, conversations, interviews, and performances on the subjects of design and script writing, cognitive science, gaming, augmented reality, and communication.

Oobject has a collection of Dieter Rams’ distinctive work for Braun.

Dieter Rams’ 40 year stint at Braun until 1995 redefined the world of product design, taking pure modernism to the world of gadgets. He is the direct inspiration for much of Apple’s product design after Steve Jobs returned and in many aspects his work is more rigorous and more coherent than Apple’s.

I hadn’t seen this massive speaker before:

A lovely collection of hand-lettered American department store logos from the late 19th and early 20th century.

Kern Type is a game that compares your kerning efforts to those of professional designers. It’s surprisingly fun. (thx, damien)

From Fathom, a copy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein constructed from found type on the web…as the book goes on, the type gets less legible.

The incomplete fonts found in the PDFs were reassembled into the text of Frankenstein based on their frequency of use. The most common characters are employed at the beginning of the book, and the text devolves into less common, more grotesque shapes and forms toward the end.

Title Scream is a collection of 8-bit video game title screens. Not just static images either…animated GIFs, yo.

A couple years ago, I pointed to a 10-minute clip of a longer documentary called The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Some kind soul has put the whole thing up on Vimeo:

This witty and original film is about the open spaces of cities and why some of them work for people while others don’t. Beginning at New York’s Seagram Plaza, one of the most used open areas in the city, the film proceeds to analyze why this space is so popular and how other urban oases, both in New York and elsewhere, measure up. Based on direct observation of what people actually do, the film presents a remarkably engaging and informative tour of the urban landscape and looks at how it can be made more hospitable to those who live in it.

Update: The Vimeo video has been taken down, but you can find it on The Internet Archive.

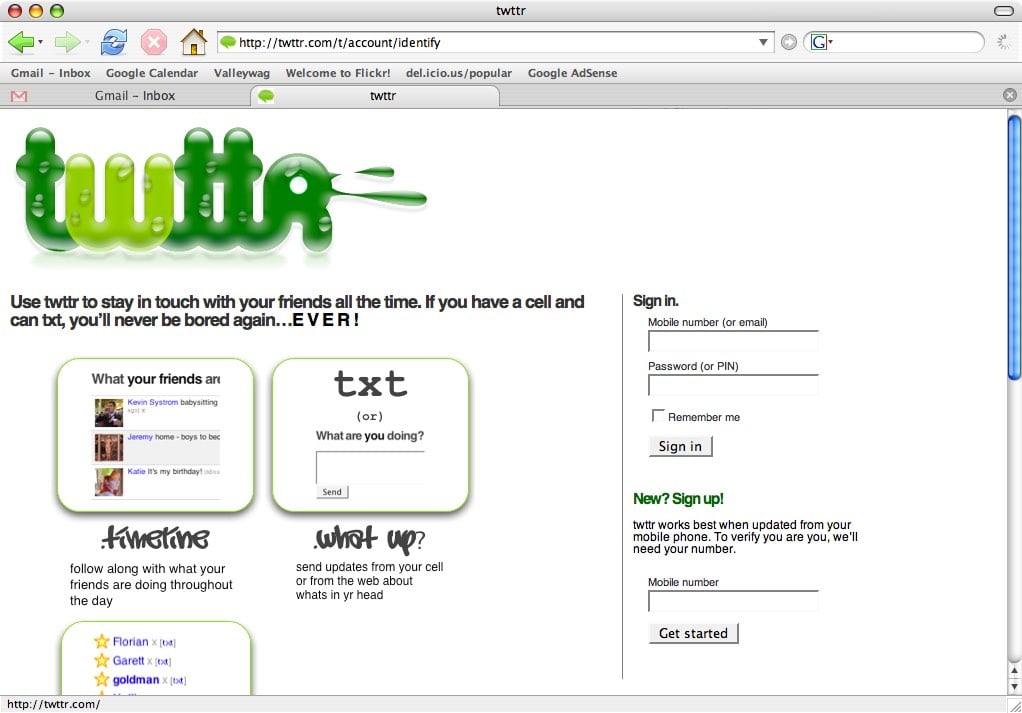

Inspired in part by my post on the original Twitter homepage, Serge Keller collected a bunch of screenshots of early web sites, including the very first web page, an early Microsoft design, and the White House’s initial site. Some sites haven’t changed all that much…Amazon and Craigslist in particular have retained much of the design DNA over the years.

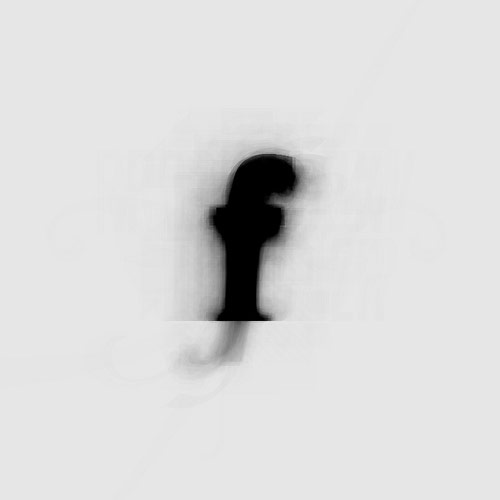

Moritz Resl took all of the fonts installed on his computer and averaged them together to make a new font: the average font.

The full alphabet is available on Flickr. (via stellar)

Or at least a very early version. From humble beginnings…

ps. Here’s an early Facebook screenshot, an early Google homepage, and Yahoo’s homepage circa 1994, and an early screencap of Tumblr’s dashboard.

Update: If you look at the screenshot closely, there’s a familiar name at the top of the “What your friends…” box: Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom (his Twitter user id is 380…meaning that he was one of the first 400 people to sign up for the service).

Stay Connected