kottke.org posts about Covid-19

Dr. Katelyn Jetelina (aka Your Local Epidemiologist) has a frustrating update on how Covid vaccines are probably going to work this fall under the ideologically corrupt Trump regime.

The FDA is expected to license the Covid-19 vaccine. Word is that the label will be restricted to adults 65+ and people at high risk.

The Vaccine Integrity Project and professional organizations likely won’t align with RFK Jr.’s FDA license, which will cause confusion.

If you’re younger than 65 and don’t have a chronic condition, could you still get it after the label change?

Yes, but it will be complicated. While a provider could prescribe it off-label, in practice, it’s likely that most people won’t be able to access it that way.

Jetelina continues:

If you’re under 65 and not high risk, the window to get a Covid-19 vaccine is right now — before the FDA label changes. Once it happens, access will be limited immediately (if it isn’t already). CVS is no longer booking appointments. As far as we know, Walgreens and local pharmacies still are.

That was as of Monday — no idea if that’s still the case. And of course, because this is the United States, insurance will probably be a mess too:

Recommendations from these two organizations are really important for insurers. The hope is they see them and cover all vaccines, regardless of what RFK does. It also provides extra information to physicians who will prescribe off-label if RFK Jr’s FDA changes the label (as expected) this Friday.

We will not know if any of these recommendations affect insurance coverage until insurance companies confirm coverage.

[insert a lot of profanity here; seriously, this makes me so incandescently mad that if I wrote anything more it would contain every fucking swear word I know and then some]

Sources: Aug 18 thread on Bluesky, Aug 20 thread on Bluesky, Aug 18 newsletter.

From David Wallace-Wells, a reminder that those who were considered alarmists at the beginning of the pandemic were ultimately proved right — it actually was an alarming situation.

Today, the official Covid death toll in the United States stands at 1.22 million. Excess mortality counts, which compare the total number of all-cause deaths to a projection of what they would have been without the pandemic, run a little higher — about 1.5 million.

In other words, the alarmists were closer to the truth than anyone else. That includes Anthony Fauci, who in March 2020 predicted 100,000 to 200,000 American deaths and was called hysterical for it. The same was true of the British scientist Neil Ferguson, whose Imperial College model suggested that the disease might ultimately infect more than 80 percent of Americans and kill 2.2 million of us. Thankfully, the country was vaccinated en masse long before 80 percent were infected…

I’m also going to point out that those who were labeled alarmists about the impact of Donald Trump’s presidencies were also “closer to the truth than anyone else”, certainly closer than all those centrist “pundits”. I’m particularly thinking of those who knew when they woke up on November 9th to a Trump victory that Roe v Wade was toast and that Americans’ civil rights would be taken away and were called “hysterical” (there’s that word again) for saying so.

Hey, everyone. I just wanted to update you on what’s been happening here at KDO HQ. As you might have noticed (and if my inbox is any indication, you have), I have pivoted to posting almost exclusively about the coup happening in the United States right now. My focus will be on this crisis for the foreseeable future. I don’t yet know to what extent other things will make it back into the mix. I still very much believe that we need art and beauty and laughter and distraction and all of that, but I also believe very strongly that this situation is too important and potentially dangerous to ignore. And it is largely being ignored by a mainstream press that has been softened up by years of conservative pushback, financial pressures, and hollowing out by Facebook & Google. But I have an independent website and a platform, and I’m going to use it the way that I have always used it: to inform people about the truth of the world (as best as I understand it) and what I feel is important.

I have pivoted like this a couple of times before: in the aftermath of 9/11 and during the pandemic. This situation feels as urgent now as those events did then. Witnessing the events of this past weekend, I felt very much like I did back in March 2020, before things shut down here in the US — you could see this huge tidal wave coming and everyone was still out on the beach sunbathing because the media and our elected officials weren’t meeting the moment. I believe that if this coup is allowed to continue and succeed, it will completely alter the course of American history — so I feel like I have no choice but to talk about it.

If you need to check out, I totally understand. I’ve heard from many readers over the years that some of you come to the site for a break from the horrible news of the world, and I know this pivot goes against that. I expect I will lose some readers and members over this — the membership page is right here if you’d like to change your status. For those who choose to continue to support the site, no matter what, my deep thanks and appreciation to you.

I’ll end on a personal note. I’ve talked a little about the impact that covering the pandemic for two years had on me, particularly in this post about Ed Yong’s talk at XOXO:

It was hard to hear about how his work “completely broke” him. To say that Yong’s experience mirrored my own is, according to the mild PTSD I’m experiencing as I consider everything he related in that video, an understatement. We covered the pandemic in different ways, but like Yong, I was completely consumed by it. I read hundreds(/thousands?) of stories, papers, and posts a week for more than a year, wrote hundreds of posts, and posted hundreds of links, trying to make sense of what was happening so that, hopefully, I could help others do the same. The sense of purpose and duty I felt to my readers — and to reality — was intense, to the point of overwhelm.

Like Yong, I eventually had to step back, taking a seven-month sabbatical in 2022. I didn’t talk about the pandemic at all in that post, but in retrospect, it was the catalyst for my break. Unlike Yong, I am back at it: hopefully more aware of my limits, running like it’s an ultramarathon rather than a sprint, trying to keep my empathy for others in the right frame so I can share their stories effectively without losing myself.

Covering the pandemic broke me. I spent the weekend and most of Monday wrestling with myself and asking, “Do you really want to put yourself through that again?” I could easily just go on posting like this existential threat to the United States isn’t happening. Like I said before, I believe we need — like they are actually necessary for life — art and beauty and laughter and distraction…and continuing to cover them would be a noble and respectable undertaking. But I eventually realized, thanks in part ot an intense session with my therapist on Tuesday, that in order to be true to myself, I need to do this.

Thankfully, I am in a much better place, mental health-wise, than I was 5 years ago. I know myself better and know how to take care of myself when I am professionally stressed out. There may be times when I need to step away and I thank you for your patience in advance. I hope that you’re doing whatever it is you need to do to take yourselves. 💞

Regarding comments: I haven’t been turning them on for any of the posts about the coup. I am trying to figure out how to turn them back on and not have the discussions mirror the sorts of unhelpful patterns that social media has conditioned us into following when discussing political issues online. I have turned them on for this post, but would encourage you to reflect on kottke.org’s community guidelines if you choose to participate; the short version: “be kind, generous, & constructive, bring facts, and try to leave the place better than you found it”. Thanks.

My favorite presentation at XOXO this year was Ed Yong’s talk about the pandemic, journalism, his work over the past four years, and the personal toll that all those things took on him. I just watched the entire thing again, riveted the whole time.

Hearing how thoughtfully & compassionately he approached his work during the pandemic was really inspirational: “My pillars are empathy, curiosity, and kindness — and much else flows from that.” And his defense of journalism, especially journalism as “a caretaking profession”:

For people who feel lost and alone, we get to say through our work: you are not. For people who feel like society has abandoned them and their lives do not matter, we get to say: actually, they fucking do. We are one of the only professions that can do that through our work and that can do that at scale — a scale commensurate with many of the crises that we face.

Then, it was hard to hear about how his work “completely broke” him. To say that Yong’s experience mirrored my own is, according to the mild PTSD I’m experiencing as I consider everything he related in that video, an understatement. We covered the pandemic in different ways, but like Yong, I was completely consumed by it. I read hundreds(/thousands?) of stories, papers, and posts a week for more than a year, wrote hundreds of posts, and posted hundreds of links, trying to make sense of what was happening so that, hopefully, I could help others do the same. The sense of purpose and duty I felt to my readers — and to reality — was intense, to the point of overwhelm.

Like Yong, I eventually had to step back, taking a seven-month sabbatical in 2022. I didn’t talk about the pandemic at all in that post, but in retrospect, it was the catalyst for my break. Unlike Yong, I am back at it: hopefully more aware of my limits, running like it’s an ultramarathon rather than a sprint, trying to keep my empathy for others in the right frame so I can share their stories effectively without losing myself.1

I didn’t get a chance to meet Yong in person at XOXO, so: Ed, thank you so much for all of your marvelous work and amazing talk and for setting an example of how to do compassionate, important work without compromising your values. (And I love seeing your bird photos pop up on Bluesky.)

Zoë Schlanger writing for the Atlantic: Prepare for a ‘Gray Swan’ Climate.

The way to think about climate change now is through two interlinked concepts. The first is nonlinearity, the idea that change will happen by factors of multiplication, rather than addition. The second is the idea of “gray swan” events, which are both predictable and unprecedented. Together, these two ideas explain how we will face a rush of extremes, all scientifically imaginable but utterly new to human experience.

It’s the nonlinearity that’s always worried me about the climate crisis — and is the main source of my skepticism that it’s “fixable” at this point. Think about another nonlinear grey swan event: the Covid-19 pandemic. When was it possible to stop the whole thing in its tracks? When 10 people were infected? 50? 500? With a disease that spreads linearly, let’s say that stopping the spread when 20 people are infected is twice as hard as when 10 are infected — with nonlinear spread, it’s maybe 4x or 10x or 20x harder. When you reach a number like 20,000 or 100,000 infected over a wide area, it becomes nearly impossible to stop without extraordinary effort.

In thinking about the climate crisis, whatever time, effort, and expense halting global warming (and the myriad knock-on effects) may have required in 1990, let’s say it doubled by 2000. And then it didn’t just double again in the next ten years, it tripled. And then from 2010 to 2020, it quadrupled. An intact glacier in 1990 is waaaaay easier and cheaper to save than one in 2010 that’s 30% melted into the ocean; when it’s 75% melted in 2020, there’s really no way to get that fresh water back out of the ocean and into ice form.

It’s like the compounding interest on your student loans when you’re not making the minimum payments — not only does the amount you owe increase each month, the increase increases. And at a certain point, the balance is actually impossible to pay off at your current resource level.1 It’s hard to say where we are exactly on our climate repayment curve (and what the interest rate is), but we’ve not been making the minimum payments for awhile now and the ocean’s repossessing our glaciers and ice shelves and…

Madeline Miller (Circe, Song of Achilles) got sick in February 2020 with what turned out to be Covid, which then turned into Long Covid. It has profoundly affected her life (gift link).

I reached out to doctors. One told me I was “deconditioned” and needed to exercise more. But my usual jog left me doubled over, and when I tried to lift weights, I ended up in the ER with chest pains and tachycardia. My tests were normal, which alarmed me further. How could they be normal? Every morning, I woke breathless, leaden, utterly depleted.

Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate enough to compose sentences. Writing had been my haven since I was 6. Now, it was my family’s livelihood. I kept looking through my pre-covid novel drafts, desperately trying to prod my sticky, limp brain forward. But I was too tired to answer email, let alone grapple with my book.

When people asked how I was, I gave an airy answer. Inside, I was in a cold sweat. My whole future was dropping away. Looking at old photos, I was overwhelmed with grief and bitterness. I didn’t recognize myself. On my best days, I was 30 percent of that person.

I turned to the internet and discovered others with similar experiences. In fact, my symptoms were textbook — a textbook being written in real time by “first wavers” like me, comparing notes and giving our condition a name: long covid.

Even if Miller were physically able to get back to some semblance of “normal life”, the current policies and attitudes w/r/t Covid make it next to impossible.

Despite the crystal-clear science on the damage covid-19 does to our bodies, medical settings have dropped mask requirements, so patients now gamble their health to receive care. Those of us who are high-risk or immunocompromised, or who just don’t want to roll the dice on death and misery, have not only been left behind — we’re being actively mocked and pathologized.

I’ve personally been ridiculed, heckled and coughed on for wearing my N95. Acquaintances who were understanding in the beginning are now irritated, even offended. One demanded: How long are you going to do this? As if trying to avoid covid was an attack on her, rather than an attempt to keep myself from sliding further into an abyss that threatens to swallow my family.

I cannot remember where I read this (it was likely more than a year ago), but it would be more accurate/helpful if we thought of the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus as a chronic vascular disease (aka Long Covid) that often comes with short-term symptoms and acute, life-threatening effects instead of the other way around.

From The Atlantic, 23 Pandemic Decisions That Actually Went Right, the result of interviews with more than a dozen pandemic experts.

17. Basic research spending matters. The COVID vaccines wouldn’t have been ready for the public nearly as quickly without a number of existing advances in immunology, Anthony Fauci, the former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told us. Scientists had known for years that mRNA had immense potential as a delivery platform for vaccines, but before SARS-CoV-2 appeared, they hadn’t had quite the means or urgency to move the shots to market. And research into vaccines against other viruses, such as RSV and MERS, had already offered hints about the sorts of genetic modifications that might be needed to stabilize the coronavirus’s spike protein into a form that would marshal a strong, lasting immune response.

In a piece about how the pace of improvement in the current crop of AI products is vastly outstripping the ability of society to react/respond to it, Ezra Klein uses this cracker of a phrase/concept: “the difficulty of living in exponential time”.

I find myself thinking back to the early days of Covid. There were weeks when it was clear that lockdowns were coming, that the world was tilting into crisis, and yet normalcy reigned, and you sounded like a loon telling your family to stock up on toilet paper. There was the difficulty of living in exponential time, the impossible task of speeding policy and social change to match the rate of viral replication. I suspect that some of the political and social damage we still carry from the pandemic reflects that impossible acceleration. There is a natural pace to human deliberation. A lot breaks when we are denied the luxury of time.

But that is the kind of moment I believe we are in now. We do not have the luxury of moving this slowly in response, at least not if the technology is going to move this fast.

Covid, AI, and even climate change (e.g. the effects we are seeing after 250 years of escalating carbon emissions)…they are all moving too fast for society to make complete sense of them. And it’s causing problems and creating opportunities for schemers, connivers, and confidence tricksters to wreck havoc.

You may have seen the online kerfuffle a few weeks ago about a study that was released recently that indicated that there was no evidence that masks work against respiratory illnesses (see Bret Stephen’s awful ideologically driven piece in the NY Times for instance). As many experts said at the time, that’s not what the review of the studies actually meant and the organization responsible recently apologized and clarified the review’s assertions.

In a typically well-argued and well-researched piece for the NY Times, Zeynep Tufekci explains what the review actually shows and why the science is clear that masks do work.

Scientists routinely use other kinds of data besides randomized reviews, including lab studies, natural experiments, real-life data and observational studies. All these should be taken into account to evaluate masks.

Lab studies, many of which were done during the pandemic, show that masks, particularly N95 respirators, can block viral particles. Linsey Marr, an aerosol scientist who has long studied airborne viral transmission, told me even cloth masks that fit well and use appropriate materials can help.

Real-life data can be complicated by variables that aren’t controlled for, but it’s worth examining even if studying it isn’t conclusive.

Japan, which emphasized wearing masks and mitigating airborne transmission, had a remarkably low death rate in 2020 even though it did not have any shutdowns and rarely tested and traced widely outside of clusters.

David Lazer, a political scientist at Northeastern University, calculated that before vaccines were available, U.S. states without mask mandates had 30 percent higher Covid death rates than those with mandates.

Randomized trials are difficult to do with masks and are not the only way to scientifically prove something. I’m hoping for an update that the entire premise of that Stephens piece is incorrect and will be removed from the Times’ website, but I don’t think it’s going to happen.

From Maastricht University in The Netherlands, this is a fantastic animation of the lifecycle of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it invades and then multiplies in the human lung. A more scientific version is available as well. Great explanation but I love the visual style of this. They used textures similar to stop motion animations — e.g. the proteins look like clay and the cell membranes seem to be made of felt. (via carl zimmer)

Theater historian Debra Caplan published a Twitter thread yesterday about Eugene Ionesco’s 1959 play, Rhinoceros.

In 1959, Eugene Ionesco wrote the absurdist play Rhinoceros in which one by one, an entire town of people suddenly transform into rhinos. At first, people are horrified but as the contagion spreads, (almost) everyone comes to accept that turning into a rhinoceros is fine.

Rhinoceros is a play about conformity and mob mentality and mass delusion, about how easy it is for people to accept outrageous/unacceptable things simply because everyone else is doing it.

In the end, the protagonist Berenger is the only human left.

Even reading that first bit of the thread, my mind jumped immediately to the pandemic, particularly the present moment we’re in with falling mask mandates and other discarded and ignored public safety protections. And that’s Caplan’s take too:

Over the last few weeks, as mitigation measures drop, millions of Americans who were previously cautious about Covid (and millions more who never were) have decided that it’s time to move on and pretend that it’s 2019 again.

Bars and restaurants are packed with unmasked people, mask mandates hardly exist anywhere and are no longer tied to infection rates, the new CDC map makes it look like everything is under control, and we seem to have all collectively decided that Covid is “over.”

Let’s be clear about what is actually happening here.

The idea that we can live with Covid WITHOUT any mitigation measures and expect things to turn out ok (both for individuals and as a society) is a lie.

We are watching an astounding mass delusion unfold in real time.

See also The New Normal, about shifting baselines.

Fear tends to diminish over time when a risk remains constant. You can only respond for so long. After a while, it recedes to the background, seemingly no matter how bad it is.

In his newest piece for The Atlantic, Ed Yong explores why, despite more than 6 million official deaths worldwide and almost a million official deaths in the US, the toll of the pandemic isn’t provoking a massive social reckoning. This is a hell of an opening paragraph:

The United States reported more deaths from COVID-19 last Friday than deaths from Hurricane Katrina, more on any two recent weekdays than deaths during the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more last month than deaths from flu in a bad season, and more in two years than deaths from HIV during the four decades of the AIDS epidemic. At least 953,000 Americans have died from COVID, and the true toll is likely even higher because many deaths went uncounted. COVID is now the third leading cause of death in the U.S., after only heart disease and cancer, which are both catchall terms for many distinct diseases. The sheer scale of the tragedy strains the moral imagination. On May 24, 2020, as the United States passed 100,000 recorded deaths, The New York Times filled its front page with the names of the dead, describing their loss as “incalculable.” Now the nation hurtles toward a milestone of 1 million. What is 10 times incalculable?

And it just keeps going from there — this is one of those articles so well written and packed with so much information and insight that it’s difficult not to quote the whole thing, even though it paints a bleak picture of America. Read the whole thing here. See also Yong’s accompanying Twitter thread.

Dismayed by the narrative that Americans did nothing to help each other out during the pandemic, Kathy Gilsinan took Mister Rogers’ advice and went to “look for the helpers”. The result is her new book, The Helpers: Profiles from the Front Lines of the Pandemic, a collection of profiles of those who worked with millions and millions of other Americans to combat the pandemic. From an excerpt in The Atlantic:

Paul Cary, for instance, was well known within the medical system in Aurora, Colorado, where he served as a paramedic — not only for his walrus mustache or the near-obsessive hours he put in, but also for his warmth. Harried and cynical ER nurses would light up when Cary arrived and asked after their families, cracking jokes about living the dream even as he was spending the evening ferrying gunshot victims or septic patients to the hospital. He wanted to be there for people on their worst days; that was the job. And in late March 2020, with COVID deaths mounting into the hundreds in New York City but still in the low double digits in his own state, Cary, a retired firefighter, decided to race toward the fire: He drove his ambulance 28 hours across the country to help relieve overwhelmed paramedics in New York. He did this knowing that, at 66, with a blood-clot disorder, a bad back, and other health issues, he was squarely in the demographic COVID preferred to kill.

The excerpt ends with an important point (re: “feel good” news & societal failure) and I’m going to quote it here:

People, of course, fail, and so do institutions. Individual goodwill and altruism cannot by themselves compensate for systemic weaknesses, and no kind volunteer alone will fix decades of underinvestment in public health or vulnerable supply chains for protective equipment. No feel-good story can compensate for the loss of more than 900,000 Americans or repair the heartbreak of millions of grieving loved ones. Still, there are those — many more than perhaps we expect — who look impossible odds in the eyes and fight anyway.

The Helpers: Profiles from the Front Lines of the Pandemic is available online and in bookstores now.

From Vox’s Joss Fong, a video essay on how conservatives turned against the Covid-19 vaccine in the US.

President Donald Trump presided over the fastest vaccine development process in history, leading to abundant, free vaccines in the US by the spring of 2021. Although the mRNA Covid-19 vaccines haven’t been able to stop transmission of the virus, they have been highly effective against hospitalization and death, saving hundreds of thousands of lives and rendering the majority of new Covid-19 deaths preventable.

Trump has received three doses of the vaccine. But many of his most dedicated supporters have refused, and many have died as a result. Why? Obvious culprits include misinformation on social media and Fox News and the election of Joe Biden, which placed a Democrat at the top of the US government throughout the vaccine distribution period. But if you look closely at the data, you’ll see that vaccine-hesitant conservatives largely made up their mind well before the vaccines were available and before Donald Trump lost the 2020 election.

Fong makes a compelling argument for the potential genesis of conservative vaccine denial: early on in the pandemic, in February and March 2020, prominent conservative leaders and media outlets (like Trump and Fox News) told their constituents that the threat of the pandemic and of SARS-CoV-2 has been exaggerated by journalists and liberal politicians. So, in the mind of a Fox News viewer, if the pandemic is not such a big deal, if it is “just the flu”, then why would you want to get vaccinated? Or wear a mask? Or take any precautions whatsoever? Or, most certainly, why wouldn’t you be angry at you and your kids (your kids!) being forced to do any of those things?

Bob Wachter is the chair of the Department of Medicine at the USCF medical center and last week he posted a pair of threads about what the Covid rates might look like in a month and how we might behave if that comes to pass (and if we don’t get another variant mucking things up). I’m going to quote extensively from Wachter’s threads because I think they contain some things that people need to hear right now.

In the first thread, he explains why an individual’s risk of catching Covid will likely be quite low a month from now:

The virus is the same, your immunity is the same, the chances of getting infected from a given encounter much the same. Yet I predict that I — and most of us — who are trying our best to dodge Omicron now will be more “open” next month. Does that make sense?

Yes! It’s all about community prevalence — basically the chances that the person next to you at the restaurant, the movie, or the store is infectious w/ Covid. It they’re not, your encounter is 100% safe. If they are, your encounter is as risky as it is today.

Today, near the Omicron peak, the odds an asymptomatic person has Covid is ~10% in most of U.S. At 10% prevalence, when you enter a room w/ 20 people, there’s an 88% chance that one of them has Covid. Do that enough times without masks and you’re going to get infected.

In a month — if cases fall to prior non-surge #’s — the prevalence among asymptomatic people may be more like 0.2% — even in less vaxxed regions, which’ll have more people whose immunity came from infection. (They should still get vaxxed for better & longer protection.)

0.2% means that the odds of an asymptomatic person having Covid=1-in-500. That room of 20 people: now a 4% chance (1-in-25) that someone’s infected. Not zero — you’ll still want to be careful if you’re at very high risk. But for most, % is low enough to feel pretty safe.

And because overall rates would be much lower, the chances of survival for those who do get Covid will increase because hospitals won’t be overwhelmed, testing will be more available, and antiviral medicines will be more available. Caveats:

Yes, the specter of Long Covid (for some, mild; others disabling) continues — maybe a ~5% chance in a vaxxed person. Some will look at those odds as being concerning enough that they’ll continue to act very cautiously. I probably won’t, but it’s an understandable choice.

And others who have lots of contact w/ very vulnerable people — unvaxxed who didn’t get Omicron, for example, or immunosuppressed - may also make different choices. That’s entirely reasonable.

And there’s also this…he’s fairly confident rates will be low this spring but perhaps not later in the year (because under-vaccinated people’s immunity from catching Omicron in the past 2 months will have waned):

As for me, this is why the community prevalence (cases, test pos %) will dominate my decisions. If they don’t plummet, I’ll keep my guard up until they do. And while I’m reasonably confident about the Spring, my confidence level falls as we move to later in the year.

In the second thread, Wachter talks about how we’ll know when the risk is low and shares how his behavior will change once that happens:

Add it all up & it’s clear that this Spring — w/ a milder virus & nearly 100% population immunity — may be about as safe as it gets… perhaps for many years. Thus I see this Spring as a time when everyone (especially those who have been extra careful for two years) needs to figure out how to navigate a far less risky landscape. (Cue the usual caveat: a new variant could easily screw things up, yet again.)

The bottom line is this: in a few weeks — when this surge ends — things are going to be as good as they’re likely to get for the foreseeable future.

Here’s how he’s going to know when his personal risk level is low enough to do some things differently:

What will my trigger be for switching to less cautious mode? It’s a bit arbitrary - there’s no bright line separating “too risky” & “not risky.” This means that others may come up w/ different thresholds.

Mine will be case rates <10/100K/day (recognizing that reported cases now underestimate case #’s due to home testing). I’d also like to see test positivity rates of <1%. (The math: when we reach a 1% overall rate in SF, that would translate to a ~0.5% asymptomatic positivity rate; or 1/200 asymptomatic people having Covid. At that prevalence, in a room of 15 folks, there’s a 7% chance that at least 1 has Covid.)

So what does that mean in terms of shifting behavior? Here’s Wachter’s personal plan w/ his acceptable level of risk:

The main questions center on indoor spaces crowded with unmasked people of uncertain vaccination status. Small indoor groups, visiting friends & family, indoor dining: all fine, without masks.

If I had school-aged kids who were fully vaccinated, I’d be comfortable without masks in school, particularly if there were a school-wide vaccine requirement and good ventilation.

My practice will be to always carry a KN95, and to don it in very crowded, poorly ventilated spaces with lots of unmasked people, particularly in parts of the U.S. or world with low vax or high case rates. I can’t tell you how crowded or how poorly ventilated, any more than I can say how likely rain needs to be in forecast before I grab an umbrella. I’ll just trust my Spidey Sense: how long I’ll be in space, how awkward wearing a mask will be, whether folks are speaking, yelling, singing, or just standing around. Does it feel scary?

At least at first, I’ll still mask on public transit (trains, planes) & shopping — crowded public spaces w/ lots of unmasked people. Once masks are no longer mandated, I don’t think I’ll mask at the hospital unless I’m seeing a patient with respiratory symptoms.

Both threads are worth a careful read to catch all the caveats and to get a full picture of his reasoning regarding risk and behavior. Hopefully reading them will give you a similar sense of empowerment and hope that they gave me.

For The Atlantic, Ed Yong writes about an idea that has gained a certain amount of traction in recent weeks as hospital systems have been overwhelmed by the Omicron surge: medical care for unvaccinated people should be limited. Yong says that’s a very bad idea:

I ran this argument past several ethicists, clinicians, and public-health practitioners. Many of them sympathized with the exasperation and fear behind the sentiment. But all of them said that it was an awful idea — unethical, impractical, and founded on a shallow understanding of why some people remain unvaccinated.

“It’s an understandable response out of frustration and anger, and it is completely contrary to the tenets of medical ethics, which have stood pretty firm since the Second World War,” Matt Wynia, a doctor and ethicist at the University of Colorado, told me. “We don’t use the medical-care system as a way of meting out justice. We don’t use it to punish people for their social choices.” The matter “is pretty cut-and-dry,” Sara Murray, a hospitalist at UC San Francisco, added. “We have an ethical obligation to provide care for people regardless of the choices they made, and that stands true for our unvaccinated patients.”

Unvaccinated people are unvaccinated for a wide variety of reasons, many of them structural constraints beyond their control. Yong connects the care of the unvaccinated to the difficulty in receiving quality care already faced by women, Black people, and disabled people:

As health-care workers become more exhausted, demoralized, and furious, they might also unconsciously put less effort into treating unvaccinated patients. After all, implicit biases mean that many groups of people already receive poorer care despite the ethical principles that medicine is meant to uphold. Complex illnesses that disproportionately affect women, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis, dysautonomia, and now long COVID, are often dismissed because of stereotypes of women as hysterical and overly emotional. Black people are undertreated for pain because of persistent racist beliefs that they are less sensitive to it or have thicker skin. Disabled people often receive worse care because of ingrained beliefs that their lives are less meaningful. These biases exist-but they should be resisted. “Stigma and discrimination as a prism for allocating health-care services is already embedded in our society,” Goldberg told me. “The last thing we should do is to celebrate it.”

That is a compelling argument and provides a necessary dose of empathy for those of us who might feel betrayed by people who are unvaccinated at this point in the pandemic. Blaming individuals for these collective responsibilities and failures is of a kind with asserting that mask-wearing and vaccination are solely personal choices rather than necessary collective actions to be undertaken by communities to keep people safer. This is the same sort of individualist thinking that has people focused on their personal “carbon footprint” instead of what massive corporations, high-emissions industries, and governments should be doing to address the climate crisis.

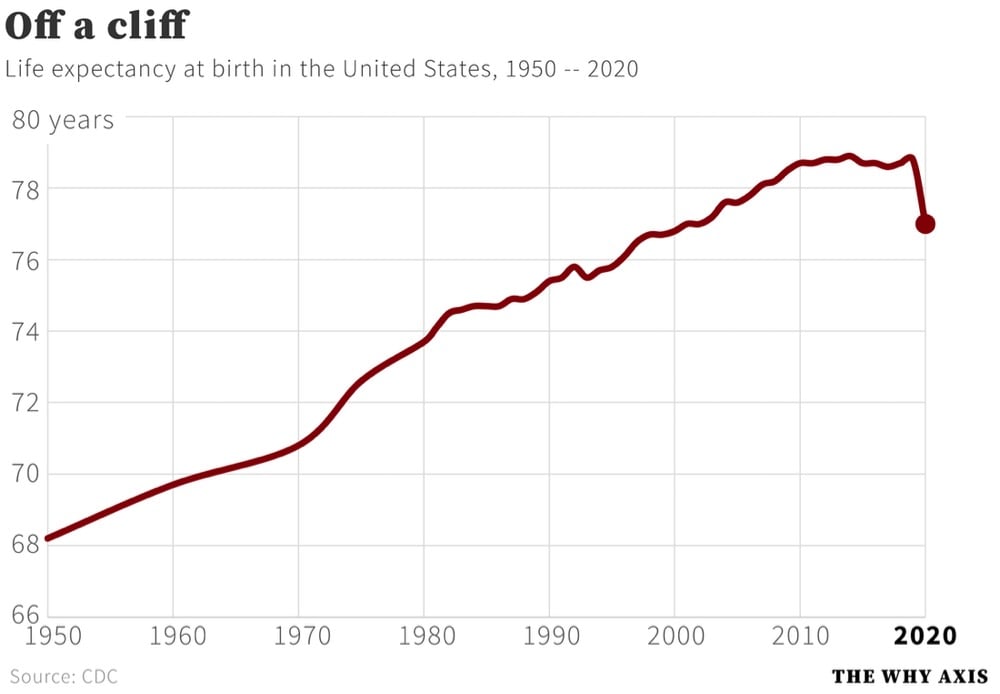

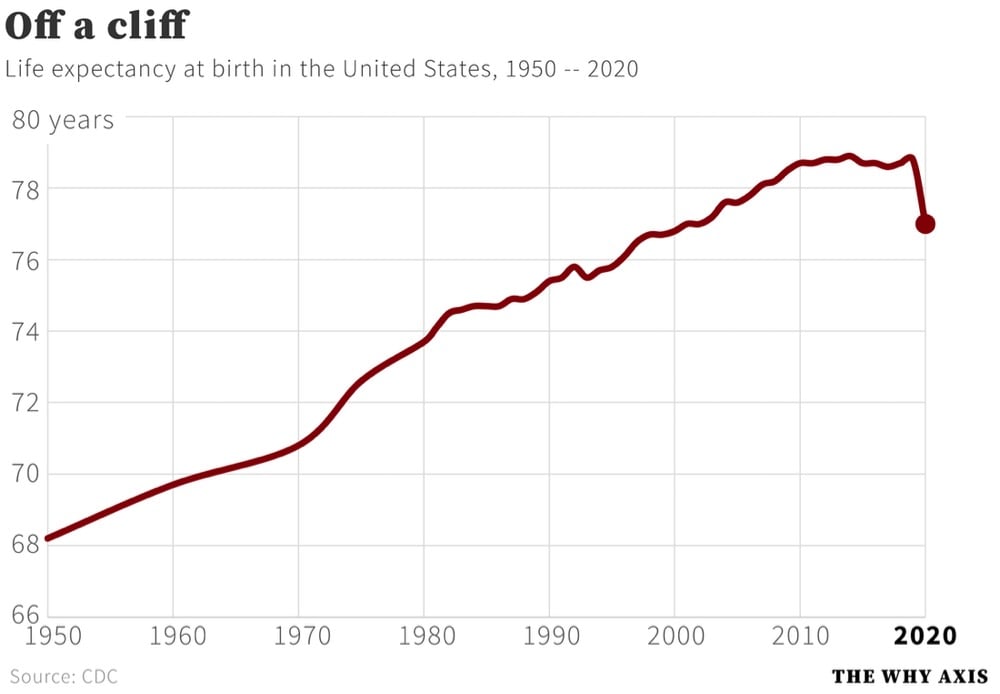

The CDC recently released their report on Mortality in the United States, 2020 and this graph of US life expectancy at birth since 1950 by Christopher Ingraham dramatically summarizes the report’s main finding:

That’s a decrease in life expectancy of 1.8 years from 2019. Here are some more of the report’s significant findings:

In 2020, life expectancy at birth was 77.0 years for the total U.S. population — a decrease of 1.8 years from 78.8 years in 2019. For males, life expectancy decreased 2.1 years from 76.3 in 2019 to 74.2 in 2020. For females, life expectancy decreased 1.5 years from 81.4 in 2019 to 79.9 in 2020.

In 2020, the difference in life expectancy between females and males was 5.7 years, an increase of 0.6 year from 2019.

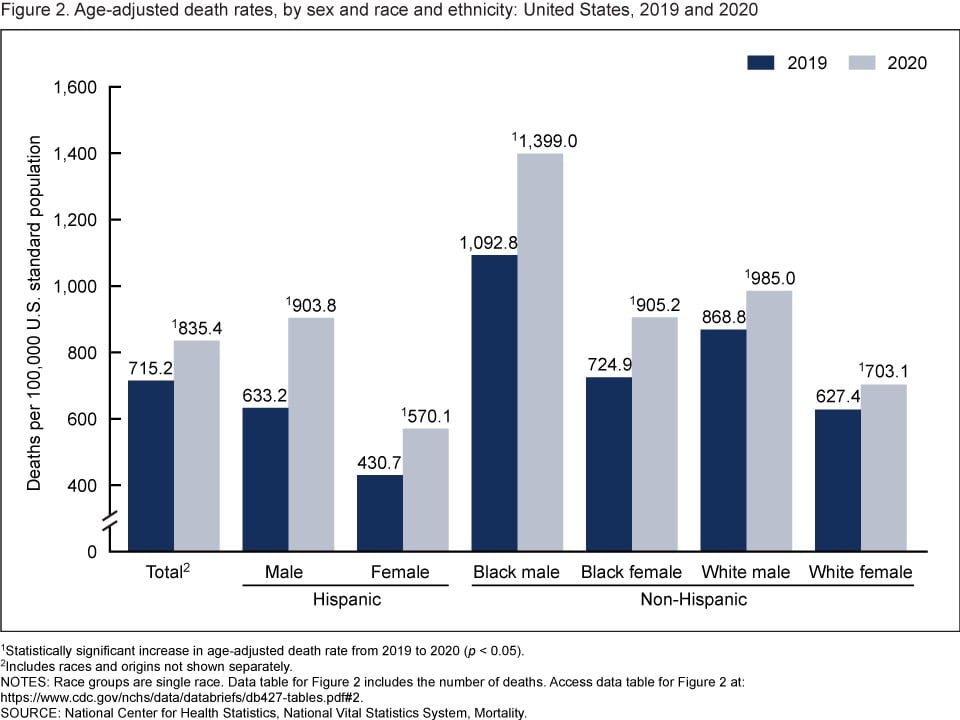

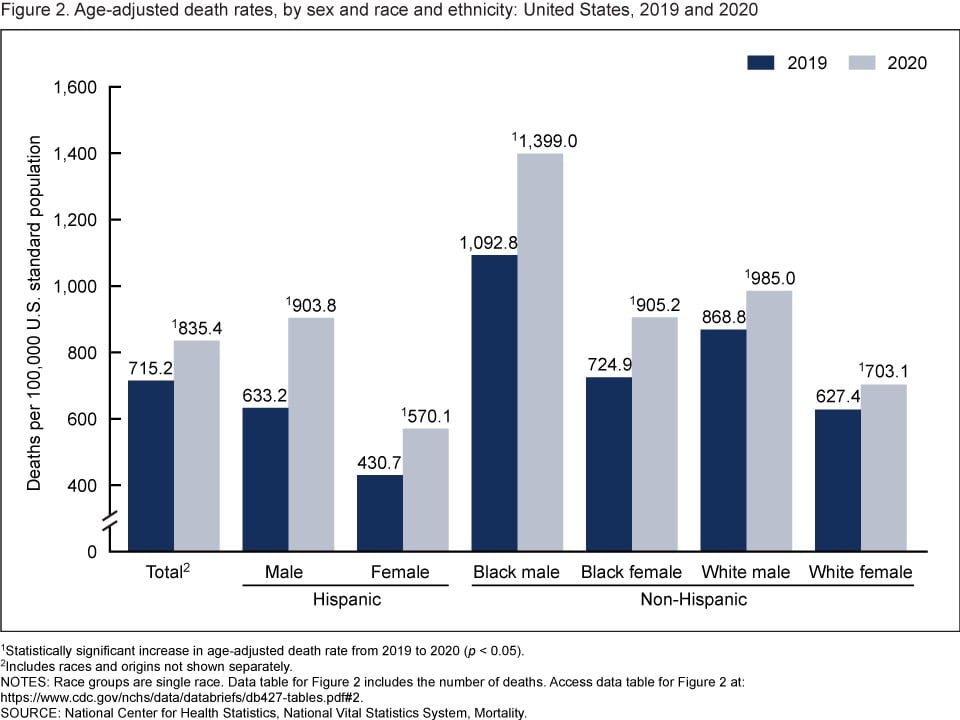

The age-adjusted death rate for the total population increased 16.8% from 715.2 per 100,000 standard population in 2019 to 835.4 in 2020. Age-adjusted death rates increased in 2020 from 2019 for all race-ethnicity-sex groups, increasing 42.7% for Hispanic males, 32.4% for Hispanic females, 28.0% for non-Hispanic Black males, 24.9% for non-Hispanic Black females, 13.4% for non-Hispanic White males, and 12.1% for non-Hispanic White females.

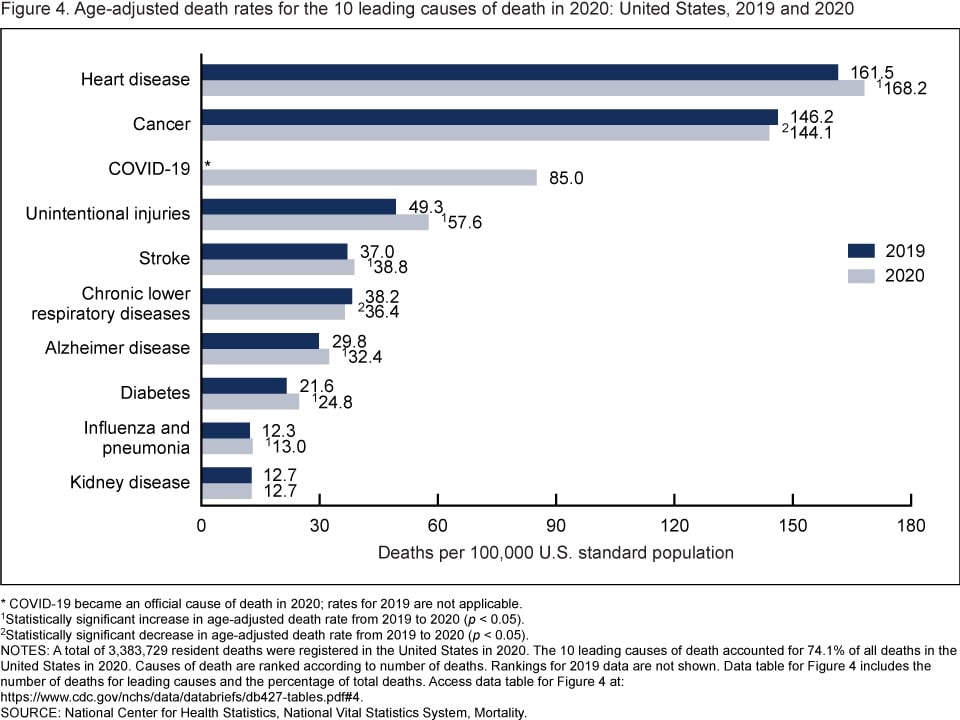

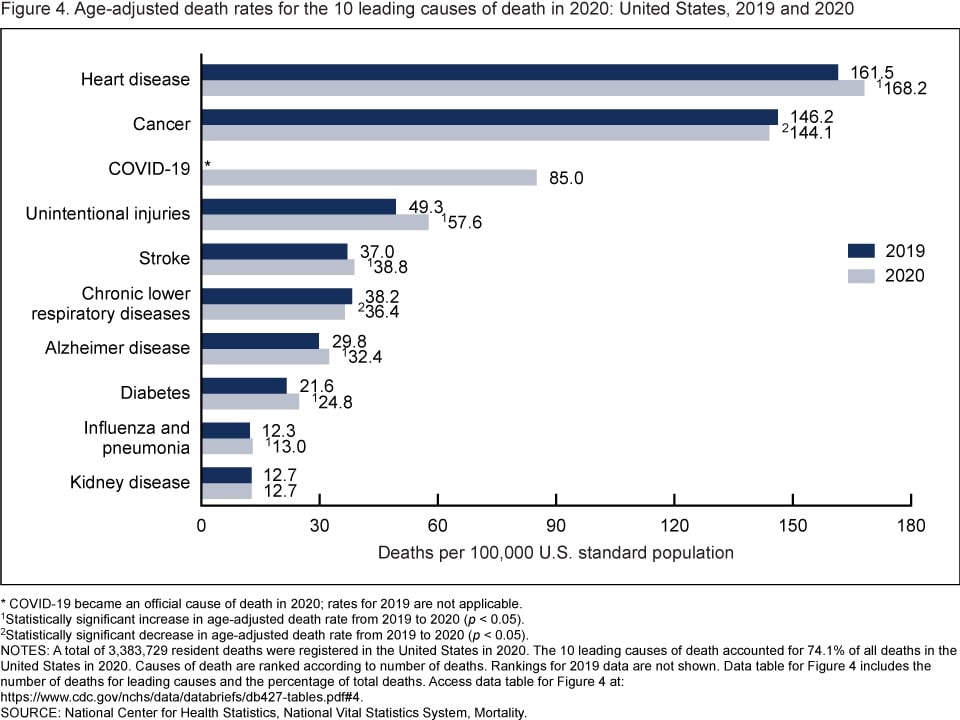

In 2020, 9 of the 10 leading causes of death remained the same as in 2019. The top leading cause was heart disease, followed by cancer. COVID-19, newly added as a cause of death in 2020, became the 3rd leading cause of death. Of the remaining leading causes in 2020 (unintentional injuries, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and kidney disease), 5 causes changed ranks from 2019. Unintentional injuries, the 3rd leading cause in 2019, became the 4th leading cause in 2020. Chronic lower respiratory diseases, the 4th leading cause in 2019, became the 6th. Alzheimer disease, the 6th leading cause in 2019, became the 7th. Diabetes, the 7th leading cause in 2019, became the 8th. Kidney disease, the 8th leading cause in 2019, became the 10th leading cause in 2020. Stroke, and influenza and pneumonia, remained the 5th and 9th leading causes, respectively. Suicide dropped from the list of 10 leading causes in 2020.

And from the report’s summary:

From 2019 to 2020, the age-adjusted death rate for the total population increased 16.8%. This single-year increase is the largest since the first year that annual mortality data for the entire United States became available. The decrease in life expectancy for the total population of 1.8 years from 2019 to 2020 is the largest single-year decrease in more than 75 years.

Since more people in the US died of Covid in 2021 than in 2020, I’d expect the decline life expectancy and the rise in death rate to continue.

This piece, from Ed Yong, is not at all surprising: America Is Not Ready for Omicron.

America was not prepared for COVID-19 when it arrived. It was not prepared for last winter’s surge. It was not prepared for Delta’s arrival in the summer or its current winter assault. More than 1,000 Americans are still dying of COVID every day, and more have died this year than last. Hospitalizations are rising in 42 states. The University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, which entered the pandemic as arguably the best-prepared hospital in the country, recently went from 70 COVID patients to 110 in four days, leaving its staff “grasping for resolve,” the virologist John Lowe told me. And now comes Omicron.

Will the new and rapidly spreading variant overwhelm the U.S. health-care system? The question is moot because the system is already overwhelmed, in a way that is affecting all patients, COVID or otherwise. “The level of care that we’ve come to expect in our hospitals no longer exists,” Lowe said.

The real unknown is what an Omicron cross will do when it follows a Delta hook. Given what scientists have learned in the three weeks since Omicron’s discovery, “some of the absolute worst-case scenarios that were possible when we saw its genome are off the table, but so are some of the most hopeful scenarios,” Dylan Morris, an evolutionary biologist at UCLA, told me. In any case, America is not prepared for Omicron. The variant’s threat is far greater at the societal level than at the personal one, and policy makers have already cut themselves off from the tools needed to protect the populations they serve. Like the variants that preceded it, Omicron requires individuals to think and act for the collective good — which is to say, it poses a heightened version of the same challenge that the U.S. has failed for two straight years, in bipartisan fashion.

The main point:

Here, then, is the problem: People who are unlikely to be hospitalized by Omicron might still feel reasonably protected, but they can spread the virus to those who are more vulnerable, quickly enough to seriously batter an already collapsing health-care system that will then struggle to care for anyone — vaccinated, boosted, or otherwise. The collective threat is substantially greater than the individual one. And the U.S. is ill-poised to meet it.

Also from Yong: he recently cancelled his 40th birthday party because of Omicron and wrote about how he thought through the decision.

If someone got sick, I know others could too. A week later, many of my friends will spend Christmas with their own families. At best, a cluster of infections at the birthday party would derail those plans, creating days of anxious quarantine or isolation, and forcing the people I love to spend time away from their loved ones. At worst, people might unknowingly carry the virus to their respective families, which might include elderly, immunocompromised, unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, or otherwise vulnerable people. Being born eight days before Christmas creates almost the perfect conditions for one potential super-spreader event to set off many more.

As has been the case the entire pandemic, our political and public health systems are not equipped to collectively combat this virus, so it falls to individuals to make good choices for our communities. It’s a nearly impossible thing to ask to pandemic-weary folks to focus in again on making good personal choices and even harder to achieve if few are willing to do it, but goddammit we have to try.

This is such an interesting article on vaccine avoidance in America by a primary care doctor & sociologist who have studied the phenomenon in America and other places. As more data has come in about the pandemic and vaccination program, the main differentiator in whether someone is willing to get a vaccine or not is class.

Over the past four decades, governments have slashed budgets and privatized basic services. This has two important consequences for public health. First, people are unlikely to trust institutions that do little for them. And second, public health is no longer viewed as a collective endeavor, based on the principle of social solidarity and mutual obligation. People are conditioned to believe they’re on their own and responsible only for themselves. That means an important source of vaccine hesitancy is the erosion of the idea of a common good.

Americans began thinking about health care decisions this way only recently; during the 1950s polio campaigns, for example, most people saw vaccination as a civic duty. But as the public purse shrunk in the 1980s, politicians insisted that it’s no longer the government’s job to ensure people’s well-being; instead, Americans were to be responsible only for themselves and their own bodies. Entire industries, such as self-help and health foods, have sprung up on the principle that the key to good health lies in individuals making the right choices.

Almost more than anything else, the pandemic has shown how damaged the US is from decades of neglect of the common good and how vulnerable we are to things like disease and political coups.

Last week, a worrisome variant of SARS-CoV-2 burst into the public consciousness: the Omicron variant. The concern among scientists and the public at large is substantial, but it is unfortunately going to take a few weeks to figure out whether those concerns are warranted. For a measured take on what we know now and what we can expect, read these two posts by epidemiologist Dr. Katelyn Jetelina (as well as this one on vaccines).

B.1.1.529 has 32 mutations on the spike protein alone. This is an insane amount of change. As a comparison, Delta had 9 changes on the spike protein. We know that B.1.1.529 is not a “Delta plus” variant. The figure below shows a really long line, with no previous Delta ancestors. So this likely means it mutated over time in one, likely immunocompromised, individual.

Of these, some mutations have properties to escape antibody protection (i.e. outsmart our vaccines and vaccine-induced immunity). There are several mutations association with increased transmissibility. There is a mutation associated with increased infectivity.

That sounds bad but again, we presently do not have enough information to know for sure about any of this. As Jetelina concludes in one of the posts:

We still have more questions than answers. But we will get them soon. Do not take Omicron lightly, but don’t abandon hope either. Our immune systems are incredible.

None of this changes what you can to do right now: Ventilate spaces. Use masks. Test if you have symptoms. Isolate if positive. Get vaccinated. Get boosted.

This Science piece by Kai Kupferschmidt also provides a great overview about where we’re at with Omicron, without the sensationalism.

Whether or not Omicron turns out to be another pandemic gamechanger, the lesson we should take from it (but probably won’t) is that grave danger is lurking in that virus and we need to get *everyone* *everywhere* vaccinated, we need free and ubiquitous rapid testing *everywhere*, we need to focus on indoor ventilation, we need to continue to use measures like distancing and mask-wearing, and we need to keep doing all of the other things in the Swiss cheese model of pandemic defense. Anything else is just continuing our idiotic streak with this virus of fucking around and then finding out. (via jodi ettenberg & eric topol)

In the United States and in many other countries around the world, we’re slowly shifting away from the Covid-19 pandemic to SARS-CoV-2 being endemic (like the flu), Dr. Lucy McBride argues that we need to recalibrate our risk calculations and expectations of what’s safe & dangerous. From A COVID Serenity Prayer in The Atlantic:

For the past 18 months, my patients have craved straightforward answers: a simple “Yes-it’s perfectly safe” or “Go for it. Have fun!” or even a “No, you absolutely cannot” to quiet the endless loops of risk calculations. But medicine is not about certainty. It never has been.

The two things that patients want-reassurance that they won’t get COVID-19 and permission to engage in life-I cannot deliver, and I never will be able to. SARS-CoV-2 is here to stay. The virus will be woven into our everyday existence much like RSV, influenza, and other common coronaviruses are. The question isn’t whether we’ll be exposed to the novel coronavirus; it’s when.

And although many of us will inevitably get COVID-19, for the majority of vaccinated people, it won’t be so bad. The vaccines weren’t designed to wholly prevent COVID-19; they transformed it into a manageable illness like the flu.

That means that, from a decision-making perspective, we’re starting to reach the acceptance phase of the pandemic: a time when we must recalibrate our individual risk gauges, which have been completely thrown out of whack. The approach I’m embracing with patients boils down to a secular version of the serenity prayer. We need “the serenity to accept the things [we] cannot change, courage to change the things [we] can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Using data from Johns Hopkins, this time lapse video shows the spread of Covid-19 across the US from Feb 2020 to Sept 2021. This looks so much like small fires exploding into raging infernos and then dying down before flaring up all over again. Indeed, forest fire metaphors seem to be particularly useful in describing pandemics like this.

Think of COVID-19 as a fire burning in a forest. All of us are trees. The R0 is the wind speed. The higher it is, the faster the fire tears through the forest. But just like a forest fire, COVID-19 needs fuel to keep going. We’re the fuel.

In other forest fire metaphorical scenarios, people are ‘kindling’, ‘sparks being thrown off’ (when infecting others) and ‘fuel’ (when becoming infected). In these cases, fire metaphors convey the dangers posed by people being in close proximity to one another, but without directly attributing blame: people are described as inanimate entities (trees, kindling, fuel) that are consumed by the fire they contribute to spread.

See also A Time Lapse World Map of Every Covid-19 Death (from July 2020).

Ed Yong: We’re Already Barreling Toward the Next Pandemic. The US is throwing too little money at high-tech, ultimately private sector solutions but much of the problem comes down to our underfunded public health system and “profoundly unequal society”.

“To be ready for the next pandemic, we need to make sure that there’s an even footing in our societal structures,” Seema Mohapatra, a health-law expert at Indiana University, told me. That vision of preparedness is closer to what 19th-century thinkers lobbied for, and what the 20th century swept aside. It means shifting the spotlight away from pathogens themselves and onto the living and working conditions that allow pathogens to flourish. It means measuring preparedness not just in terms of syringes, sequencers, and supply chains but also in terms of paid sick leave, safe public housing, eviction moratoriums, decarceration, food assistance, and universal health care. It means accompanying mandates for social distancing and the like with financial assistance for those who might lose work, or free accommodation where exposed people can quarantine from their family. It means rebuilding the health policies that Reagan began shredding in the 1980s and that later administrations further frayed. It means restoring trust in government and community through public services. “It’s very hard to achieve effective containment when the people you’re working with don’t think you care about them,” Arrianna Marie Planey, a medical geographer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told me.

I don’t know if this is comforting or what, but psychologist Steven Taylor published a book two months before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic called The Psychology of Pandemics that predicted many of the behaviors we’ve been seeing over the past 18+ months, including masking backlash, the acceptance of conspiracy theories, vaccine resistance, and wholesale denial that the pandemic is even happening.

Taylor would know because he predicted it. He wrote a remarkable little book back in 2019 called “The Psychology of Pandemics.” Its premise is that pandemics are “not simply events in which some harmful microbe ‘goes viral,’” but rather are mass psychological phenomena about the behaviors, attitudes and emotions of people.

The book came out pre-COVID and yet predicts every trend and trope we’ve been living for 19 months now: the hoarding of supplies like toilet paper at the start; the rapid spread of “unfounded rumors and fake news”; the backlash against masks and vaccines; the rise and acceptance of conspiracy theories; and the division of society into people who “dutifully conform to the advice of health authorities” — sometimes compulsively so — and those who “engage in seemingly self-defeating behaviors such as refusing to get vaccinated.”

He has no crystal ball, he says, it’s just that all of this has happened before. A lot of people believed the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 was spread by the Germans through Bayer aspirin. It’s all based on basic psychology as to how people react to health emergencies.

The denialists and refuseniks today are engaging in what the psychology field calls “psychological reactance.” It’s “a motivational response to rules, regulations, or attempts at persuasion that are perceived as threatening one’s autonomy and freedom of choice,” the book describes. Think what happens when someone says “Eat your broccoli.”

Following onto that is what psychologists term “motivated reasoning.” That’s when people stick with their story even if the facts obviously are contrary to it, as a form of “comforting delusion,” Taylor says. The book covers “unrealistic optimism bias,” in which people in pandemics are prone to convincing themselves that it can’t or won’t happen to them.

The book almost wasn’t even released at all — Taylor’s publisher told him the book was “interesting, but no one’s going to want to read it”.

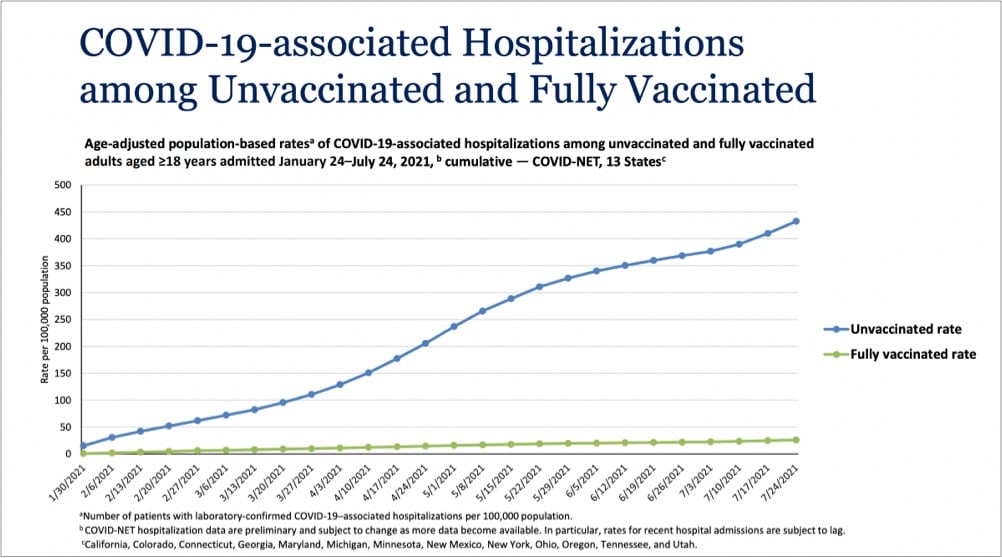

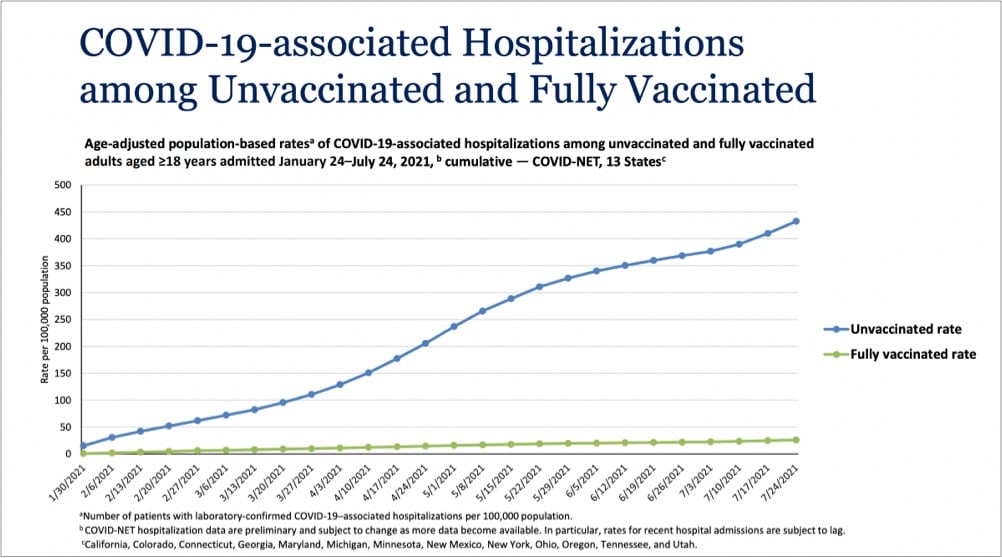

It may seem like sometimes that with the pandemic, we’re back to square one. With the much more contagious Delta variant in play and an increasing number of breakthrough infections, the efficacy of these vaccines that we thought were amazing maybe aren’t? (Or maybe we just need to readjust our expectations?) But in terms of what these vaccines were specifically developed for — reducing & preventing severe disease and death — they are still very much doing their job. Just take a look at this graph from a White House Covid-19 press briefing yesterday:

Even with Delta endemic in the country, the vaccines are providing extraordinary protection against infections severe enough to land folks in the hospital. In a recent CDC study of infections and hospitalizations in Los Angeles County, they report that on July 25, the hospitalization rate of unvaccinated people was 29.2 times that of fully vaccinated persons. 29 times the protection is astounding for a medical intervention. These vaccines work, we’re lucky to have them, and we need to get as many people worldwide as we can vaccinated as quickly as we can. Period.

You might want to take a deep breath or do a couple of laps around the house before watching this video about a community in the Ozarks with a very low Covid-19 vaccination rate. Here’s a sample. An ICU patient wearing an oxygen mask on why he didn’t get vaccinated:

I’m more of a libertarian and I don’t like being told what I have to do. I’m still not completely 100% sold on the inoculation.

Video narrator:

It was eerie to hear Christopher insist on his individual freedoms even as he struggled to breathe.

Can you hear me screaming all the way from my desk to wherever you are? I don’t like being told what I have to do?! Fucking hell. And this:

There’s no better place to see the impact of this political rhetoric than in the hospital. Only about 50 percent of the staff are vaccinated. None of the unvaccinated staffers were willing to talk.

Absolutely maddening. I want off this ride.

Dan Sinker writes for The Atlantic about how navigating Covid risks, politically motivated bullshit, and America’s failing infrastructure has broken parents during the pandemic: Parents Are Not Okay.

Instead it was a year in limbo: school on stuttering Zoom, school in person and then back home again for quarantine, school all the time and none of the time. No part of it was good, for kids or parents, but most parts of it were safe, and somehow, impossibly, we made it through a full year. It was hell, but we did it. We did it.

Time collapsed and it was summer again, and, briefly, things looked better. We began to dream of normalcy, of trips and jobs and school. But 2021’s hot vax summer only truly delivered on the hot part, as vaccination rates slowed and the Delta variant cut through some states with the brutal efficiency of the wildfires that decimated others. It happened in a flash: It was good, then it was bad, then we were right back in the same nightmare we’d been living in for 18 months.

And suddenly now it’s back to school while cases are rising, back to school while masks are a battleground, back to school while everyone under 12 is still unvaccinated. Parents are living a repeat of the worst year of their lives-except this time, no matter what, kids are going back.

Almost every parent I know is struggling with exactly this: trying to keep their kids (and family and friends) safe from Covid-19 while balancing the social & emotional wellbeing of everyone concerned and not getting a lot of help from their governments or communities. Remote school is no longer an option, few infrastructure upgrades have been made to improve ventilation in schools, no vaccine mandates for teachers or staff, parents fighting administrators about vaccine & mask mandates, and everyone is trying to do complex risk calculations about sending their can’t-yet-be-vaccinated kids into buildings with other kids whose parents, you suspect, are not vaccinated and aren’t taking any precautions in states where Delta is endemic. All while trying to work and remain sane somehow? And most of the parents I know have resources — they have steady income & savings, live in safe communities, and have friends & family to fall back on when times get tough. Those who don’t? I truly do not know how they are doing any of this without incurring significant, long-term trauma for parents and kids. We, inasmuch as we’re still a “we” in America, are failing them all.

For The Atlantic, Katherine Wu writes about the difficulty of communicating how vaccines work and how they protect individuals and communities from disease: Vaccines Are Like Sunscreen… No, Wait, Airbags… No, Wait…

Unfortunately, communal benefit is harder to define, harder to quantify, and harder to describe than individual protection, because “it’s not the way Americans are used to thinking about things,” Neil Lewis, a behavioral scientist and communications expert at Cornell, told me. That’s in part because communal risk isn’t characteristic of the health perils people in wealthy countries are accustomed to facing: heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer. Maybe that’s part of why we gravitate toward individual-focused comparisons. Slipping into a pandemic-compatible, population-based frame of mind is a big shift. In the age of COVID-19, “there’s been a lot of focus on the individual,” Lewis told me. That’s pretty at odds “with how infection works.”

As someone who has struggled with analogizing the virus & vaccines, I was nodding my head a lot while reading this. Something I’ve noticed in recent years that Wu didn’t get into is that readers desire precision in metaphors and analogies, even though metaphor is — by definition! — not supposed to be taken literally. People seem much more interested in taking analogies apart, identifying what doesn’t work, and discarding them rather than — more generously and constructively IMO — using them as the author intended to better understand the subject matter. The perfect metaphor doesn’t exist because then it wouldn’t be a metaphor.

I’m just going to go ahead and say it right up front here: if you had certain expectations in May/June about how the pandemic was going to end in the US (or was even thinking it was over), you need to throw much of that mindset in the trash and start again because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has changed the game. I know this sucks to hear,1 but Delta is sufficiently different that we need to reset and stop assuming we can solely rely on the vaccines to stop Covid-19 from spreading. Ed Yong’s typically excellent piece on how delta has changed the pandemic’s endgame is helping me wrap my head around this.

But something is different now — the virus. “The models in late spring were pretty consistent that we were going to have a ‘normal’ summer,” Samuel Scarpino of the Rockefeller Foundation, who studies infectious-disease dynamics, told me. “Obviously, that’s not where we are.” In part, he says, people underestimated how transmissible Delta is, or what that would mean. The original SARS-CoV-2 virus had a basic reproduction number, or R0, of 2 to 3, meaning that each infected person spreads it to two or three people. Those are average figures: In practice, the virus spread in uneven bursts, with relatively few people infecting large clusters in super-spreading events. But the CDC estimates that Delta’s R0 lies between 5 and 9, which “is shockingly high,” Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University, told me. At that level, “its reliance on super-spreading events basically goes away,” Scarpino said.

In simple terms, many people who caught the original virus didn’t pass it to anyone, but most people who catch Delta create clusters of infection. That partly explains why cases have risen so explosively. It also means that the virus will almost certainly be a permanent part of our lives, even as vaccines blunt its ability to cause death and severe disease.

And a reminder, as we “argue over small measures” here in the US, that most of the world is in a much worse place:

Pandemics end. But this one is not yet over, and especially not globally. Just 16 percent of the world’s population is fully vaccinated. Many countries, where barely 1 percent of people have received a single dose, are “in for a tough year of either lockdowns or catastrophic epidemics,” Adam Kucharski, the infectious-disease modeler, told me. The U.S. and the U.K. are further along the path to endemicity, “but they’re not there yet, and that last slog is often the toughest,” he added. “I have limited sympathy for people who are arguing over small measures in rich countries when we have uncontrolled epidemics in large parts of the world.”

Where I think Yong’s piece stumbles a little is in its emphasis of the current vaccines’ protection against infection from Delta. As David Wallace-Wells explains in his piece Don’t Panic, But Breakthrough Cases May Be a Bigger Problem Than You’ve Been Told, vaccines still offer excellent protection against severe infection, hospitalization, and death, but there is evidence that breakthrough infections are more common than many public health officials are saying. The problem lies with the use of statistics from before vaccines and Delta were prevalent:

Almost all of these calculations about the share of breakthrough cases have been made using year-to-date 2021 data, which include several months before mass vaccination (when by definition vanishingly few breakthrough cases could have occurred) during which time the vast majority of the year’s total cases and deaths took place (during the winter surge). This is a corollary to the reassuring principle you might’ve heard, over the last few weeks, that as vaccination levels grow we would expect the percentage of vaccinated cases will, too — the implication being that we shouldn’t worry too much over panicked headlines about the relative share of vaccinated cases in a state or ICU but instead focus on the absolute number of those cases in making a judgment about vaccine protection across a population. This is true. But it also means that when vaccination levels were very low, there were inevitably very few breakthrough cases, too. That means that to calculate a prevalence ratio for cases or deaths using the full year’s data requires you to effectively divide a numerator of four months of data by a denominator of seven months of data. And because those first few brutal months of the year were exceptional ones that do not reflect anything like the present state of vaccination or the disease, they throw off the ratios even further. Two-thirds of 2021 cases and 80 percent of deaths came before April 1, when only 15 percent of the country was fully vaccinated, which means calculating year-to-date ratios means possibly underestimating the prevalence of breakthrough cases by a factor of three and breakthrough deaths by a factor of five. And if the ratios are calculated using data sets that end before the Delta surge, as many have been, that adds an additional distortion, since both breakthrough cases and severe illness among the vaccinated appear to be significantly more common with this variant than with previous ones.

Vaccines are still the best way to protect yourself and your community from Covid-19. The vaccines are still really good, better than we could have hoped for. But they’re not magic and with the rise of Delta (and potentially worse variants on the horizon if the virus is allowed to continue to spread unchecked and mutate), we need to keep doing the other things (masking, distancing, ventilation, etc.) in order to keep the virus in check and avoid lockdowns, school closings, outbreaks, and mass death. We’ve got the tools; we just need to summon the will and be in the right mindset.

The Panola Project is a short film by Rachael DeCruz and Jeremy Levine that follows the efforts of local convenience store owner Dorothy Oliver to get the people in her small Alabama community vaccinated against Covid-19. A trusted member of her community, Oliver teams up with county commissioner Drucilla Russ-Jackson to call & go door-to-door, talking with people one-on-one, cajoling and telling personal stories of loss to get folks signed up for a mobile vaccination clinic.

In the film, Oliver and Russ-Jackson arrange for a hospital to set up a pop-up site in Panola, but the site will only be established if they get at least forty people to sign up to take the vaccine. We follow Oliver as she goes door to door, talking people into signing up, lightly cajoling them about their fears and concerns. When I asked her how she does it, her answer was disarmingly simple: “I just be nice to them,” she said. “I don’t go at them saying, ‘You gotta do that.’” DeCruz, too, was struck by the way Oliver and Jackson talked to people who were on the fence about the vaccine, an issue more often discussed with stridency of various types. “There’s this very warm and kind of loving and caring way that Dorothy and Ms. Jackson approached those conversations, even when people aren’t in agreement. And it wasn’t done in a way that’s, like, ‘I know better than you.’ “

Oliver’s charm with the skeptics is remarkable, but so is her determination to bring the vaccine to her underserved town. Most of the women and men Oliver talked to leaped at the opportunity to sign up for the vaccine. On vaccine day, they rolled down their car windows to thank her. “We appreciate y’all giving it to us, because a lot of people don’t really know where to go to take these vaccines,” one woman tells her. Vaccine hesitancy in Black communities has been harped on in the media, but those conversations can gloss over questions of availability. Levine told me that they were struck by how many people had put off vaccination for logistical rather than ideological reasons. In Panola, he says, they regularly heard people say, “I want the shot. How do I get this? I don’t have a car; how am I going to get forty miles to the closest hospital and back?”

The result? In a state with one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country, 94% of adults in Panola have been vaccinated, due in part to Oliver’s and Russ-Jackson’s efforts.

Older posts

Socials & More