Facebook Paper

Facebook’s new Paper app is pretty good. Once you get the hang of the gestures, it feels natural and very Letterpressy and smooth, which isn’t surprising considering Loren Brichter’s involvement. Check out The Verge’s review.

This site is made possible by member support. 💞

Big thanks to Arcustech for hosting the site and offering amazing tech support.

When you buy through links on kottke.org, I may earn an affiliate commission. Thanks for supporting the site!

kottke.org. home of fine hypertext products since 1998.

Facebook’s new Paper app is pretty good. Once you get the hang of the gestures, it feels natural and very Letterpressy and smooth, which isn’t surprising considering Loren Brichter’s involvement. Check out The Verge’s review.

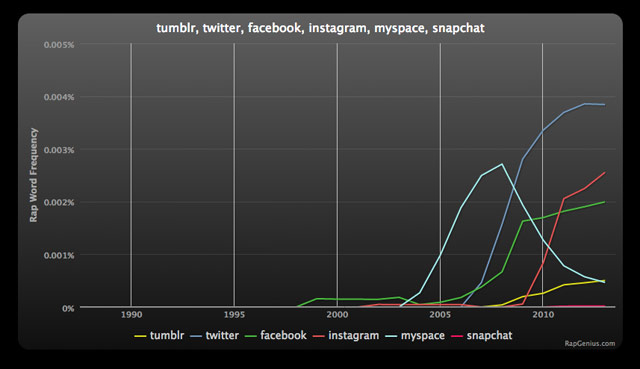

From Rap Genius, a chart showing mentions in rap songs of popular social sites and apps like Twitter and Instagram:

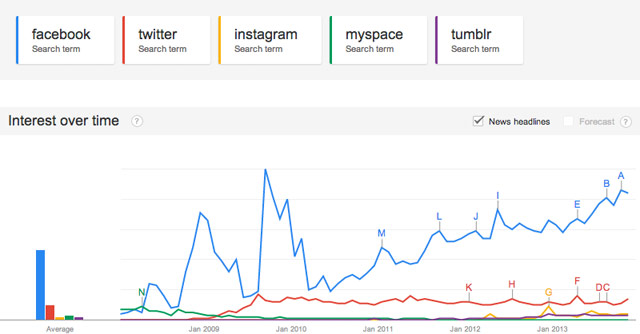

Compare with the graph for the same terms from Google News:

And here’s the graph for general search terms. (I excluded Snapchat from the Google graphs because Google wouldn’t allow 6 search terms at a time…it barely showed up in either case.) Twitter rules the rap roost, but Facebook demolishes everyone in general and news search traffic.

For his latest What If? column, Randall Munroe tackles the question “When, if ever, will Facebook contain more profiles of dead people than of living ones?”

Based on the site’s growth rate, and the age breakdown of their users over time, there are probably 10 to 20 million people who created Facebook profiles who have since died.

That’s an incredible number; most tech startups would kill (well, not really but maybe…) for that many alive users.

After receiving Facebook friend requests from Christopher Robin after several years of not hearing from him, the residents of the Hundred Acre Wood hold a meeting to talk about the new development.

“No disrespecting what’s clearly a very Emportent Meeting,” Eeyore began, “but to me it’s simple: Christopher Robin left to do who-knows-what-and-where, and we stayed here. Both of our lives went on. The way I see it, Christopher Robin was feeling lonely and sad last night — maybe his girlfriend just dumped him, maybe he got rejected from the graduate program he was hoping to get in to. He’d probably been drinking, and he started getting wistful for days-gone-by, so he searched us all on Facebook and so-on-and-so-on and there we have it. Trust me, Christopher Robin is probably relieved I [ignored his friend request]. He’s probably sitting in his apartment right now in a pair of ripped sweatpants, eating ice cream out of a tub and re-watching The Wire and thanking his stars he doesn’t have to actually still be friends with his old, mopey pal Eeyore.”

This piece by Jacqui Cheng about her experience watching kids from inner city Chicago navigate social media is interesting thoughout, but the way they use account deletion to turn Facebook into something a bit more like Snapchat is super-clever and savvy.

For example, did you know that many teens “delete” their Facebook accounts altogether every time the rest of us would just log out? They’re taking advantage of the fact that Facebook actually keeps much of your account information on its servers when you decide to “leave” the service, allowing them to stay under the radar from nosy friend, parent, or public searches while they’re not online. Their photos disappear and their status updates go on the down-low-at least until the next time they log back in by re-activating their accounts.

How long before we see a social networking app where your info is only visible when you’re actively online? And maybe you can pay to increase your visibility beyond those bounds?

This interview with a 14-year-old girl about how she uses her iPhone and social media is almost equal parts fascinating and terrifying. Some choice quotes:

“I’ll wake up in the morning and go on Facebook just … because,” Casey says. “It’s not like I want to or I don’t. I just go on it. I’m, like, forced to. I don’t know why. I need to. Facebook takes up my whole life.”

—

“I bring [my iPhone] everywhere. I have to be holding it,” Casey says. “It’s like OCD — I have to have it with me. And I check it a lot.”

—

Not having an iPhone can be social suicide, notes Casey. One of her friends found herself effectively exiled from their circle for six months because her parents dawdled in upgrading her to an iPhone. Without it, she had no access to the iMessage group chat, where it seemed all their shared plans were being made.

“She wasn’t in the group chat, so we stopped being friends with her,” Casey says. “Not because we didn’t like her, but we just weren’t in contact with her.”

—

The most important and stress-inducing statistic of all is the number of “likes” she gets when she posts a new Facebook profile picture — followed closely by how many “likes” her friends’ photos receive. Casey’s most recent profile photo received 117 “likes” and 56 comments from her friends, 19 of which they posted within a minute of Casey switching her photo, and all of which Casey “liked” personally.

“If you don’t get 100 ‘likes,’ you make other people share it so you get 100,” she explains. “Or else you just get upset. Everyone wants to get the most ‘likes.’ It’s like a popularity contest.”

—

“If I’m not watching TV, I’m on my phone. If I’m not on my phone, I’m on my computer. If I’m not doing any of those things, what am I supposed to do?” Casey says.

Josh Miller asked his 15-year-old sister about social media trends. That was six months ago, so everything has probably already changed, but it’s still an interesting read. (via digg)

Facebook has so many features that at least one of them has to be useful, right? Here’s the page on Facebook that just shows you links shared by the people you follow. No tweets, no photos, no jingoistic rants from distant cousins. Just the links. (And if you like links on Facebook, you should like kottke.org on Facebook.)

Facebook’s new Graph Search can be used to find some very unusual, disturbing, and potentially dangerous things. Like “Married people who like Prostitutes”, “Family members of people who live in China and like Falun Gong”, and “Islamic men interested in men who live in Tehran, Iran”.

Matt Haughey wrote an essay called Why I love Twitter and barely tolerate Facebook.

There’s no memory at Twitter: everything is fleeting. Though that concept may seem daunting to some (archivists, I feel your pain), it also means the content in my feed is an endless stream of new information, either comments on what is happening right now or thoughts about the future. One of the reasons I loved the Internet when I first discovered it in the mid-1990s was that it was a clean slate, a place that welcomed all regardless of your past as you wrote your new life story; where you’d only be judged on your words and your art and your photos going forward.

Facebook is mired in the past.

One of my favorite posts on street photographer Scott Schuman’s blog, The Sartorialist, consists of two photos of the same woman taken several months apart.

Schuman asked the woman how she was able to create such a dramatic change:

Actually the line that I think was the most telling but that she said like a throw-away qualifier was “I didn’t know anyone in New York when I moved here…”

I think that is such a huge factor. To move to a city where you are not afraid to try something new because all the people that labeled who THEY think you are (parents, childhood friends) are not their to say “that’s not you” or “you’ve changed”. Well, maybe that person didn’t change but finally became who they really are. I totally relate to this as a fellow Midwesterner even though my changes were not as quick or as dramatic.

I bet if you ask most people what keeps them from being who they really want to be (at least stylistically or maybe even more), the answer would not be money but the fear of peer pressure — fear of embarrassing themselves in front of a group of people that they might not actually even like anyway.

For a certain type of person, changing oneself might be one of the best ways of feeling free and in control of one’s own destiny. And in the social media world, Twitter feels like continually moving to NYC without knowing anyone whereas Facebook feels like you’re living in your hometown and hanging with everyone you went to high school with. Twitter’s we’re-all-here-in-the-moment thing that Matt talks about is what makes it possible for people to continually reinvent themselves on Twitter. You don’t have any of that Facebook baggage, the peer pressure from a lifetime of friends, holding you back. You are who your last dozen tweets say you are. And what a feeling of freedom that is.

Kent Brewster’s Who Likes Mitt allows you to watch Mitt Romney’s Facebook fans unlike him in real time. Before the election, I wondered how either candidate would utilize their social media platforms in the event of their loss, as both Mitt Romney and Barack Obama had several million followers on Twitter and Facebook. We’ll have quite some time to see the answer because at the current and unsustainable rate of abandonment, Mitt’s last follower will unlike him in just over 3 years. *181 Facebook fans left Mitt while this post was written. (via ★akuban)

Update: Now, with graphs! (thx, @colossal)

Newsweek announced yesterday that the print magazine will cease publication and the entire thing will move to an all-digital format.

Newsweek Global, as the all-digital publication will be named, will be a single, worldwide edition targeted for a highly mobile, opinion-leading audience who want to learn about world events in a sophisticated context. Newsweek Global will be supported by paid subscription and will be available through e-readers for both tablet and the Web, with select content available on The Daily Beast.

In talking about the shift on his Daily Beast blog, Andrew Sullivan notes something interesting about reading online vs. reading in print (emphasis mine):

Which is why, when asked my opinion at Newsweek about print and digital, I urged taking the plunge as quickly as possible. Look: I chose digital over print 12 years ago, when I shifted my writing gradually online, with this blog and now blogazine. Of course a weekly newsmagazine on paper seems nuts to me. But it takes guts to actually make the change. An individual can, overnight. An institution is far more cumbersome. Which is why, I believe, institutional brands will still be at a disadvantage online compared with personal ones. There’s a reason why Drudge Report and the Huffington Post are named after human beings. It’s because when we read online, we migrate to read people, not institutions. Social media has only accelerated this development, as everyone with a Facebook page now has a mini-blog, and articles or posts or memes are sent by email or through social networks or Twitter.

People do tend to read people and not institutions online but a shift away from that has already started happening. A shift back to institutions, actually. Pre-1990s, people read the Times or Newsweek or Time or whatever. In 2008, people read Andrew Sullivan’s Daily Dish or Paul Krugman’s column in the Times or Gwyneth Paltrow’s GOOP. Today, people read feeds of their friends/followees activities, interests, thoughts, and links on sites like Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, and Tumblr, i.e. the new media institutions.

Now, you may follow Daily Dish or Krugman on Twitter but that’s not quite the same as reading the sites; you’re not getting the whole post/article on Twitter, Krugman items are intermingled & fighting for attention with tweets from @horse_ebooks & Lady Gaga, and if you unfollowed Krugman altogether, you’ll find when he writes something especially good, someone else in your Twitter stream will point you to it pretty quickly. That is, Twitter or Facebook will provide you with the essential Krugman without you having to pay any attention to Krugman at all.

What that means is what blogs and the web are doing to newspapers and magazines, so might Facebook & Twitter do to blogs. Blogs might not even get the chance to be called old media before they’re handed their hats. It’ll be interesting to see how smartphone/tablet apps affect this dynamic…will apps push users/readers back toward old media institutions, individuals, or the friend-packaging institutions like Twitter?

Facebook’s going public in a few days and will finally get a real valuation attached to it. During a 2009 Burger King promotion that doled out free Whoppers for deleting some of your Facebook friends, I estimated Facebook’s valuation at about $1.8 billion.

What BK has unwittingly done here is provide a way to determine the valuation of Facebook. Let’s assume that the majority of Facebook’s value comes from the connections between their users. From Facebook’s statistics page, we learn that the site has 150 million users and the average user has 100 friends. Each friendship is requires the assent of both friends so really each user can, on average, only end half of their friendships. The price of a Whopper is approximately $2.40. That means that each user’s friendships is worth around 5 Whoppers, or $12. Do the math and:

$12/user X 150M users = $1.8 billion valuation for Facebook

At the time, Facebook’s estimated worth was anywhere between $9-15 billion, about an order of magnitude more than the company’s 2009 Whopper valuation. According to the company’s Key Facts page, Facebook has 901 million monthly active users as of the end of March 2012. Doing the math again:

$12/user X 901M users = $10.8 billion valuation for Facebook

Right now, the price range for the IPO is $34-38 a share which would put the company’s overall valuation at $104 billion, the same order of magnitude more than the current Whopper valuation.

Now, I’m no economist, but that’s a lot of hamburgers.

Writing for New York magazine, Henry Blodget explains how a young startup founder and college dropout became the CEO of a soon-to-be $100 billion company.

When talking about Zuckerberg’s most valuable personality trait, a colleague jokingly invokes the famous Stanford marshmallow tests, in which researchers found a correlation between a young child’s ability to delay gratification — devour one treat right away, or wait and be rewarded with two — with high achievement later in life. If Zuckerberg had been one of the Stanford scientists’ subjects, the colleague jokes, Facebook would never have been created: He’d still be sitting in a room somewhere, not eating marshmallows.

[Ed note: read the update below…this is likely definitely a hoax.] Intrigued by a possible connection between PT Barnum and Abe Lincoln, Nate St. Pierre travelled to the Lincoln Museum in Springfield, IL. Once there, he stumbled upon something called The Springfield Gazette, a personal newspaper made by Lincoln that is eerily similar to Facebook.

The whole Springfield Gazette was one sheet of paper, and it was all about Lincoln. Only him. Other people only came into the document in conjunction with how he experienced life at that moment. If you look at the Gazette picture above, you can see his portrait in the upper left-hand corner. See how the column of text under him is cut off on the left side? Stupid scanned picture, I know, ugh. But just to the left of his picture, and above that column of text, is a little box. And in that box you see three things: his name, his address, and his profession (attorney).

The first column underneath his picture contains a bunch of short blurbs about what’s going on in his life at the moment - work he recently did, some books the family bought, and the new games his boys made up. In the next three columns he shares a quote he likes, two poems, and a short story about the Pilgrim Fathers. I don’t know where he got them, but they’re obviously copied from somewhere. In the last three columns he tells the story of his day at the circus and tiny little story about his current life on the prairie.

Put all that together on one page and tell me what it looks like to you. Profile picture. Personal information. Status updates. Copied and shared material. A few longer posts. Looks like something we see every day, doesn’t it?

Lincoln even tried to patent the idea.

Lincoln was requesting a patent for “The Gazette,” a system to “keep People aware of Others in the Town.” He laid out a plan where every town would have its own Gazette, named after the town itself. He listed the Springfield Gazette as his Visual Appendix, an example of the system he was talking about. Lincoln was proposing that each town build a centrally located collection of documents where “every Man may have his own page, where he might discuss his Family, his Work, and his Various Endeavors.”

He went on to propose that “each Man may decide if he shall make his page Available to the entire Town, or only to those with whom he has established Family or Friendship.” Evidently there was to be someone overseeing this collection of documents, and he would somehow know which pages anyone could look at, and which ones only certain people could see (it wasn’t quite clear in the application). Lincoln stated that these documents could be updated “at any time deemed Fit or Necessary,” so that anyone in town could know what was going on in their friends’ lives “without being Present in Body.”

Man, I hope this isn’t a hoax…it’s almost too perfect. Also, queue Jesse Eisenberg saying “Abe, if you had invented Facebook, you would have invented Facebook”. (via @gavinpurcell)

Update: Ok, I’m willing to call hoax on this one based on two things. 1) The first non-engraved photograph reproduced in a newspaper was in 1880, 35 years after the Springfield Gazette was alledgedly produced. 2) The Library of Congress says that the photograph pictured in the Gazette was taken in 1846 or 1847, a year or two after the publication date. That and the low-res “I couldn’t take proper photos of them” images pretty much convinces me.

Update: And the proof…the original Springfield Gazette sans Lincoln. (via @zempf)

One of the more thought-provoking pieces on Instagram’s billion dollar sale to Facebook is Matt Webb’s Instagram as an island economy. In it, he thinks about Instagram as a closed economy:

What is the labour encoded in Instagram? It’s easy to see. Every “user” of Instagram is a worker. There are some people who produce photos — this is valuable, it means there is something for people to look it. There are some people who only produce comments or “likes,” the virtual society equivalent of apes picking lice off other apes. This is valuable, because people like recognition and are more likely to produce photos. All workers are also marketers — some highly effective and some not at all. And there’s a general intellect which has been developed, a kind of community expertise and teaching of this expertise to produce photographs which are good at producing the valuable, attractive likes and comments (i.e., photographs which are especially pretty and provocative), and a somewhat competitive culture to become a better marketer.

There are also the workers who build the factory — the behaviour-structuring instrument/forum which is Instagram itself, both its infrastructure and it’s “interface:” the production lines on the factory floor, and the factory store. However these workers are only playing a role. Really they are owners.

All of those workers (the factory workers) receive a wage. They have not organised, so the wage is low, but it’s there. It’s invisible.

Like all good producers, the workers are also consumers. They immediately spend their entire wage, and their wages is only good in Instagram-town. What they buy is the likes and comments of the photos they produce (what? You think it’s free? Of course it’s not free, it feels good so you have to pay for it. And you did, by being a producer), and access to the public spaces of Instagram-town to communicate with other consumers. It’s not the first time that factory workers have been housed in factory homes and spent their money in factory stores.

Although he doesn’t use the term explictly, Webb is talking about a company town. Interestingly, Paul Bausch used this term in reference to Facebook a few weeks ago in a discussion about blogging:

The whole idea of [blog] comments is based on the assumption that most people reading won’t have their own platform to respond with. So you need to provide some temporary shanty town for these folks to take up residence for a day or two. And then if you’re like Matt — hanging out in dozens of shanty towns — you need some sort of communication mechanism to tie them together. That sucks.

So what’s an alternative? Facebook is sort of the alternative right now: company town.

Back to Webb, he says that making actual money with Instagram will be easy:

I will say that it’s simple to make money out of Instagram. People are already producing and consuming, so it’s a small step to introduce the dollar into this.

I’m not so sure about this…it’s too easy for people to pick up and move out of Instagram-town for other virtual towns, thereby creating a ghost town and a massively devalued economy. After all, the same real-world economic forces that allowed a dozen people to build a billion dollar service in two years means a dozen other people can build someplace other than Instagram for people to hang out in, spending their virtual Other-town dollars.

Also worth a read on Facebook/Instagram: Paul Ford’s piece for New York Magazine.

Facebook, a company with a potential market cap worth five or six moon landings, is spending one of its many billions of dollars to buy Instagram, a tiny company dedicated to helping Thai beauty queens share photos of their fingernails. Many people have critical opinions on this subject, ranging from “this will ruin Instagram” to “$1 billion is too much.” And for many Instagram users it’s discomfiting to see a giant company they distrust purchase a tiny company they adore - like if Coldplay acquired Dirty Projectors, or a Gang of Four reunion was sponsored by Foxconn.

So what’s going on here?

First, to understand this deal it’s important to understand Facebook. Unfortunately everything about Facebook defies logic. In terms of user experience (insider jargon: “UX”), Facebook is like an NYPD police van crashing into an IKEA, forever - a chaotic mess of products designed to burrow into every facet of your life.

Maybe Facebook *is* good for society: teens aren’t acting as crazy during Spring Break because they don’t want to get caught doing inappropriate things on camera.

They are so afraid everyone is going to take their picture and put it online.

You don’t want to have to defend yourself later, so you don’t do it.

But spring break [in Key West] has been Facebooked into greater respectability.

“At the beach yesterday, I would put my beer can down, out of the picture every time,” Ms. Sawyer said. “I do worry about Facebook. I just know I need a job eventually.”

“Oh, no,” she recoiled. “I’m friends with my mom on Facebook.”

Facebook: Society’s Self-Surveillance Network™. (via @gavinpurcell)

Nick Bergus recently posted a link on Facebook to a 55-gallon drum of personal lubricant sold by Amazon — it’s only $1500! Then the post got sponsored and his family and friends started seeing it when they used Facebook, turning Bergus into a pitchman of sorts for an absurd amount of sex lube.

A week later, a friend posts a screen capture and tells me that my post has been showing up next to his news feed as a sponsored story, meaning Amazon is paying Facebook to highlight my link to a giant tub of personal lubricant.

Other people start reporting that they’re seeing it, too. A fellow roller derby referee. A former employee of a magazine I still write for. My co-worker’s wife. They’re not seeing just once, but regularly. Said one friend: “It has shown up as one on mine every single time I log in.”

Get used to this…promoted word of mouth is how a lot of advertising will work in the future.

BTW, as with many unusual products on Amazon, the “Customers Who Viewed This Item Also Viewed” listing (horse head mask?) and the reviews are worth checking out.

As a Fertility Specialist for Pachyderms, this was exactly what we needed to help rebuild elephant populations all over sub-saharan africa. It’s not all just Medications and IVF treatments. Some times you need a loudspeaker, a Barry White CD and a 55 Gallon drum of Lube.

More than a year ago, Facebook engineer Andrew Bosworth wrote a post about how best to work with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

I think one of the biggest mistakes people make when first working with Zuck is feeling that they can’t push back. As long as I have been at Facebook, I have been impressed with how much he prefers to be part of an ongoing discussion about the product as opposed to being its dictator. There are a number of exceptions to this, of course, but that comes with the territory. In those instances where he is quite sure what he wants, I find he is quite good at making his decisions clear and curtailing unneeded debate.

Barring that, you should feel comfortable noting potential problems with a proposal of his or, even better, suggesting alternative solutions. You shouldn’t necessarily expect to change his mind on the spot, but I find it is common for discussions to affect his thinking over a longer time period. Don’t necessarily expect acknowledgment for your role in moving the discussion forward; getting the product right should be its own reward. If you do that, you’ll find you are invited back more and more to the debate.

Facebook is certainly an interesting company…they’re a large company that appears to operate much like a small company. Will be interesting to see if they can keep that up as they get larger, go public, etc.

This is the contemporary take on the guy-meets-girl-at-party story. Guy isn’t particularly interested in girl but at some later point starts surreptitiously taking photos of her and posting them to a secret blog. Girl finds out, isn’t creeped out at all. Boy doesn’t feel shame at girl’s discovery, only that it ruined his creative outlet before “he might have gotten better at it or something”. Girl decides to interview boy for her communications class. You know, completely normal.

She messaged Walker through Facebook, and at first he seemed receptive. “He thought it was funny,” said Merker. But after an initial show of interest, Walker got skittish, canceling and rescheduling the interview repeatedly. When Merker finally sat down with him, it was only after she had managed to catch him off-guard, saying she was already in his neighborhood and offering to meet at a bar.

Walker had one condition: he wanted to do the interview “in character” as the persona he had established through the blog. That would mean interviewing Merker, too; after all, any blogger who had devoted an entire Tumblr to a single person would certainly take the opportunity to directly question his subject.

You know when Mark Zuckerberg says stuff like privacy doesn’t matter and Facebook makes formerly private information public without notice and all the tech pundits (most of whom are older than Zuck) go bananas tearing out their hair about how stupid and crazy that is? Now you know where Zuck and Facebook are coming from.

In the latest issue of the New Yorker, Ken Auletta has a profile of Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook. A lot of the article focuses on gender issues in business and technology.

Early this spring, Sandberg gathered twelve female Facebook executives in a bare, white-walled conference room to review the agenda for the company’s Women’s Leadership Day, which was scheduled for the following week. Each of them was expected to lead sessions encouraging all the female executives there to step up “into leadership” roles. “What I believe, and that doesn’t mean everyone believes it, is that there are still institutional problems and we need more flexibility in all of this stuff,” Sandberg told them. “But much too much of the conversation is on blaming others, and not enough is on taking responsibility ourselves.”

Yes, she continued, we could swap anecdotes about sexist acts. But doing so diverts women from self-improvement. She opposes all forms of affirmative action for women. “If you don’t believe there is a glass ceiling, there is no need,” she told me. She doesn’t even like voluntary efforts to keep positions open for qualified women. There’s a cost, she explained, in lost time, and a cost for women, because “people will think she’s not the best person and that job was held open for a woman.”

Thomas Weber attempted to reverse engineer the algorithm that Facebook uses for its “Top News” feed and learned some very interesting things about what Facebook chooses what to show (and not show) their users.

1. Facebook’s Bias Against Newcomers. If there’s one thing our experiment made all too clear, it’s that following 500 million people into a party means that a lot of the beer and pretzels are already long gone. Poor Phil spent his first week shouting his updates, posted several times a day, yet most of his ready-made “friends” never noticed a peep on their news feeds. His invisibility was especially acute among those with lengthy, well-established lists of friends. Phil’s perpetual conversation with the ether only stopped when we instructed our volunteers to interact with him. A dynamic which leads to…

2. Facebook’s Catch-22: To get exposure on Facebook, you need friends to interact with your updates in certain ways (more on that below). But you aren’t likely to have friends interacting with your updates if you don’t have exposure in the first place. (Memo to Facebook newcomers: Try to get a few friends to click like crazy on your items.)

This bit at the end is particularly interesting:

All the while, Facebook, like Google, continues to redefine “what’s important to you” as “what’s important to other people.” In that framework, the serendipitous belongs to those who connect directly with their friends in the real world-or at least take the time to skip their news feed and go visit their friends’ pages directly once in a while.

In a piece at the normally unlinkable TechCrunch, Adam Rifkin argues that Facebook could be bigger than Google (revenue-wise) in five years. Rifkin makes a compelling argument.

Facebook Advertising does not directly compete with the text advertisements of Google’s AdWords and AdSense. Instead Facebook is siphoning from Madison Avenue TV ad spend dollars. Television advertising represented $60 billion in 2009, or roughly one out of every two dollars spent on advertising in the U.S.; the main challenge marketers have with the Internet till recently has been that there aren’t too many places where they can reach almost everybody with one single ad spend. Facebook fixes that problem.

Dark Patterns are UI techniques designed to trick users into doing things they otherwise wouldn’t have done.

Normally when you think of “bad design”, you think of laziness or mistakes. These are known as design anti-patterns. Dark Patterns are different — they are not mistakes, they are carefully crafted with a solid understanding of human psychology, and they do not have the user’s interests in mind.

For instance, Privacy Zuckering is a dark pattern implemented by Facebook to get users to share more about themselves than they would like to. (thx, @tnorthcutt)

The New Yorker has a trio of interesting articles in their most recent issue for the discerning web/technology lady or gentlemen. First is a lengthy profile of Mark Zuckerberg, the quite private CEO of Facebook who doesn’t believe in privacy.

Zuckerberg may seem like an over-sharer in the age of over-sharing. But that’s kind of the point. Zuckerberg’s business model depends on our shifting notions of privacy, revelation, and sheer self-display. The more that people are willing to put online, the more money his site can make from advertisers. Happily for him, and the prospects of his eventual fortune, his business interests align perfectly with his personal philosophy. In the bio section of his page, Zuckerberg writes simply, “I’m trying to make the world a more open place.”

The second is a profile of Tavi Gevinson (sub. required), who you may know as the youngster behind Style Rookie.

Tavi has an eye for frumpy, “Grey Gardens”-inspired clothes and for arch accessories, and her taste in designers runs toward the cerebral. From the beginning, her blog had an element of mystery: is it for real? And how did a thirteen-year-old suburban kid develop such a singular look? Her readership quickly grew to fifty thousand daily viewers and won the ear of major designers.

And C, John Seabrook has a profile of James Dyson (sub. required), he of the unusual vacuum cleaners, unusual hand dryers, and the unusual air-circulating fan.

In the fall of 2002, the British inventor James Dyson entered the U.S. market with an upright vacuum cleaner, the Dyson DC07. Dyson was the product’s designer, engineer, manufacturer, and pitchman. The price was three hundred and ninety-nine dollars. Not only did the Dyson cost much more than most machines sold at retail but it was made almost entirely out of plastic. In the most perverse design decision of all, Dyson let you see the dirt as you collected it, in a clear plastic bin in the machine’s midsection.

Vanity Fair has a profile of hacker-turned-billionaire Sean Parker, who helped found Napster, Plaxo, and Facebook.

He has financed the businesses of numerous cohorts, merely out of affection. “He’s one of the most generous people I know,” says another associate. “Also one of the flakiest.”

Think about the following platforms and when the first traditional media activity/participation occurred in that platform’s history: Friendster, MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Foursquare, Chatroulette. It was a shorter and shorter period for each platform.*

Let’s call this the adoption half-life. It’s a bastardization of Moore’s Law, but the level of adoption required for a social platform to be covered as The Next Big Thing in social platforms will continue to decrease until NBT status is bestowed upon a platform used only by those in the media.

I’d been writing a post about this that wasn’t coming out the way I wanted, so I shelved it until I saw The Onion’s take on last fall’s New York Times’ take on Foursquare. Then I decided to jam 2 posts together.

The Onion sums this all up way more succinctly:

Aging, scared newspapermen throw themselves at the latest mobile technology trend in a humiliatingly futile attempt to remain relevant.

For his part, Foursquare founder, Dennis Crowley, had this to say:

Um, The Onion poking fun of @foursquare (and me). This is the greatest moment of my entire life.

*If someone has a LexisNexis account and can find the first mention of these platforms, I’d be grateful, but since this is the internet, I don’t need sources, mirite?

In this 28-minute presentation, Jesse Schell talks about the psychological and economic aspects of Facebook games and what that means for the future of gaming and living. If you make products or software that other people use, this is pretty much a must-see kinda thing…the last 5 or 6 minutes are dizzying, magical, and terrifying.

Data from Facebook reveals how the United States is split up into different regions like Stayathomia, Greater Texas, Dixie, and Mormonia.

Stretching from New York to Minnesota, [Stayathomia’s] defining feature is how near most people are to their friends, implying they don’t move far. In most cases outside the largest cities, the most common connections are with immediately neighboring cities, and even New York only has one really long-range link in its top 10. Apart from Los Angeles, all of its strong ties are comparatively local.

(thx, dinu)

All sorts of goodies come up during the interview, including master passwords, keeping data after it has been deleted, and the the ubersmart Facebook engineers that you can’t talk to “on a normal level”.

Stay Connected