Near the end of Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov writes:

Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?

For years, no one picked up on the fact that Sally Horner really was abducted by a man named Frank La Salle in 1948 and the crime was a definite influence on Nabokov in writing Lolita, not until Alexander Dolinin suggested it in 2005. Sarah Weinman explores the connection in Hazlitt.

On her way home from school the next day, though, the man sought her out again. Without warning, the rules had changed: Sally had to go with him to Atlantic City — the government insisted. She’d have to convince her mother he was the father of two school friends, inviting her to a seashore vacation. He would take care of the rest with a phone call and a convincing appearance at the Camden bus depot.

His name was Frank La Salle, and he was no FBI agent — rather, he was the sort G-men wanted to drive off the streets, though Sally didn’t learn that until it was far too late. It took 21 months to break free of him, after a cross-country journey from Camden, New Jersey, to San Jose, California. That five-cent notebook didn’t just alter Sally Horner’s own life, though: it reverberated throughout the culture, and in the process, irrevocably changed the course of 20th-century literature.

(via @DavidGrann)

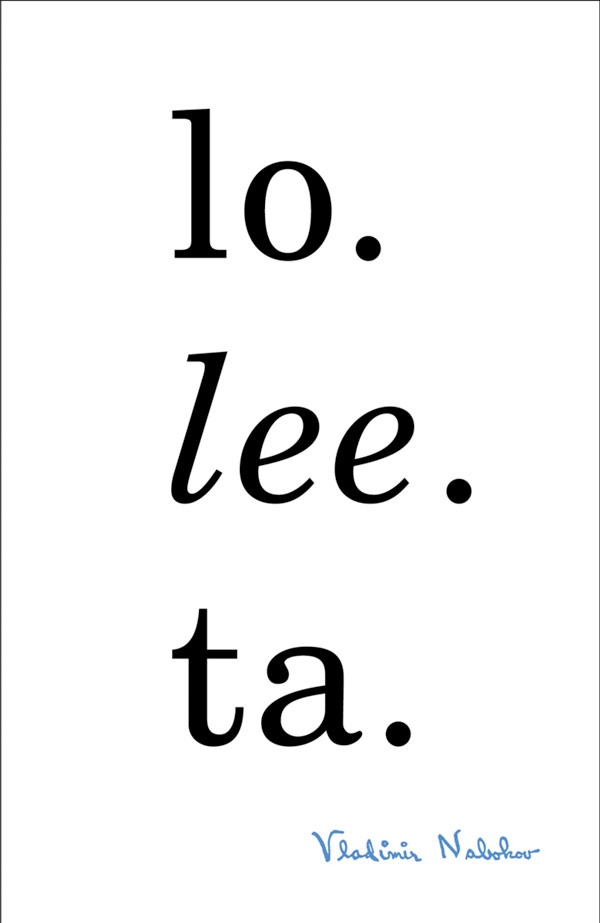

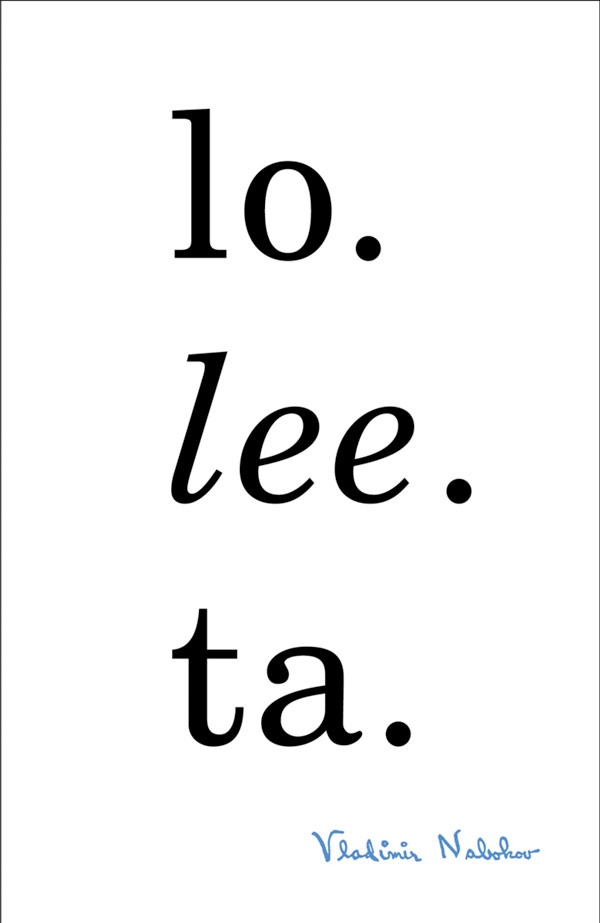

The results of a competition to design a better cover for Nabokov’s Lolita are being packaged into a book due out in June.

Among the problems Nabokov’s Lolita poses for the book designer, probably the thorniest is the popular misconception of the title character. She’s chronically miscast as a teenage sexpot-just witness the dozens of soft-core covers over the years. “We are talking about a novel which has child rape at its core,” says John Bertram, an architect and blogger who, three years ago, sponsored a Lolita cover competition asking designers to do better.

Now the contest is being turned into a book, due out in June and coedited by Yuri Leving, with essays on historical cover treatments along with new versions by 60 well-known designers, two-thirds of them women: Barbara deWilde, Jessica Helfand, Peter Mendelsund, and Jennifer Daniel, to name a few. They don’t shy away from frank sexuality, but they add layers of darkness and complication. And like Jamie Keenan’s cover — a claustrophobic room that morphs into a girl in her underwear — they provoke without asking readers to abdicate their responsibility.

Of the covers shown, Peter Mendelsund’s is a favorite:

The Times has published an extract of Vladimir Nabokov’s supposed-to-be-destroyed final novel, The Original of Laura. The book is out on Tuesday; cover by Chip Kidd.

Watch as Vladimir Nabokov reads the first paragraph of Lolita in English & Russian, shares his favorite books, and lists a bunch of things that he doesn’t like.

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.

I’m about due for a reread.

The New Yorker has some new fiction by Vladimir Nabokov that has never been published in English, a short story called Natasha. The story was recently uncovered and translated:

Written around 1924, when Nabokov was in his mid-twenties (five years after his family fled Russia, and two years after his father was assassinated in Berlin), it was discovered in the writer’s archives at the Library of Congress a couple of years ago, and was translated by his son, Dmitri.

Did Vladimir Nabokov deliberately take the idea for Lolita from a 1916 short story of the same name or did he suffer from cryptomnesia? Cryptomnesia is when you consciously forget previously learned information but subconsciously remember it. (via george, who says “It’s certainly a weird concept, that an idea can have a quantum state of being both remembered and new, and one that I think deserves more attention.”)

Nabokov on Lewis Carroll and his photography: “I always call him Lewis Carroll Carroll, because he was the first Humbert Humbert. Have you seen those photographs of him with little girls?” Nabokov aside, there’s no real evidence that Carroll did anything untoward with any of his photographic subjects. View some of Carroll’s photos here, here, and here. (via tmn)

Stay Connected