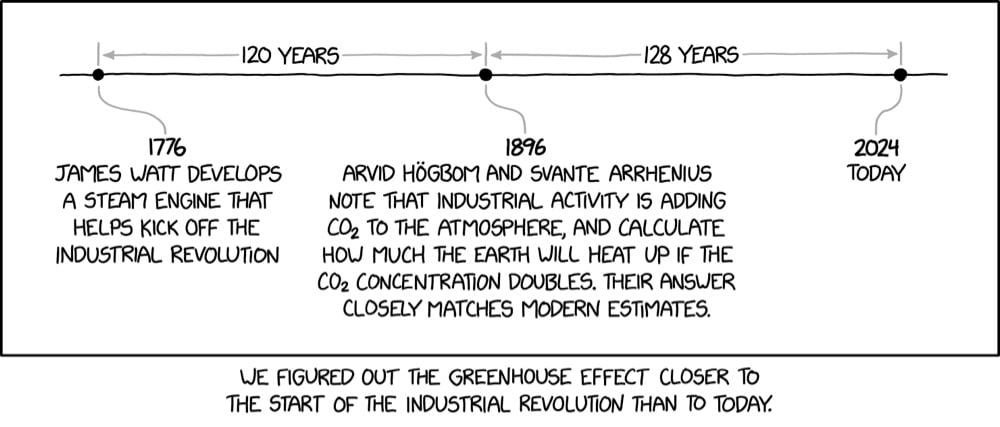

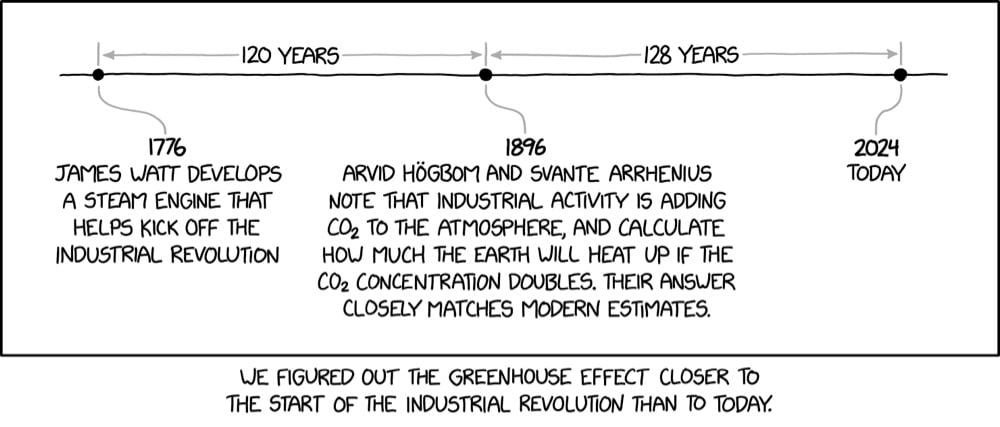

In 1896, scientists determined that industrialization was adding CO2 to the atmosphere and quantified how much it would warm the Earth. That date is closer to the start of the Industrial Revolution than to the present day.

If you’re wondering, like I did, about that 1896 date — what about Fourier and Pouillet and Tyndall and Eunice Foote? — the Wikipedia pages on the history of the discovery of the greenhouse effect and the history of climate change science are worth a read.

The warming effect of sunlight on different gases was examined in 1856 by Eunice Newton Foote, who described her experiments using glass tubes exposed to sunlight. The warming effect of the sun was greater for compressed air than for an evacuated tube and greater for moist air than dry air. “Thirdly, the highest effect of the sun’s rays I have found to be in carbonic acid gas.” (carbon dioxide) She continued: “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if, as some suppose, at one period of its history, the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its action, as well as from an increased weight, must have necessarily resulted.”

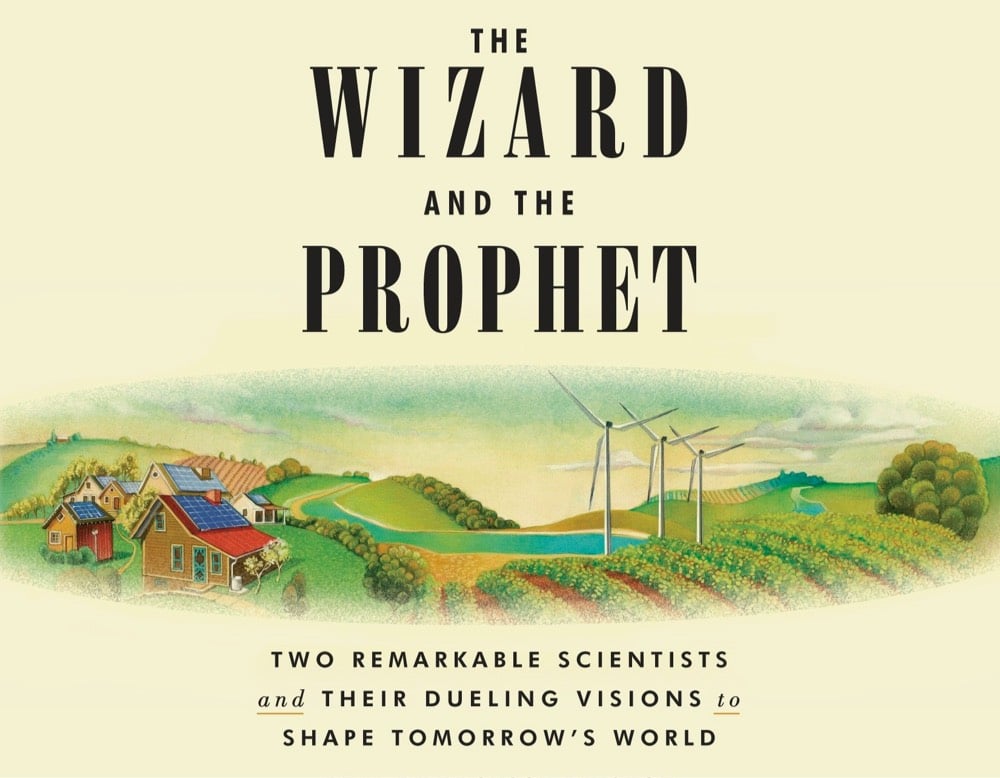

Foote’s paper went largely unnoticed until it was rediscovered in the last decade. If you’re interested, the best thing I’ve read on the history of climate change is the 7th chapter of Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet.

Last week, I was under the rock that everyone talks about and didn’t get to see Avengers: Infinity War until a couple of days ago. (Mild spoilers follow.) There’s a lot to like about the movie — I personally loved watching it — but the thing that surprised the hell out of me was how closely the motivations of Thanos and the Avengers echoed the subject of Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet.

Prophets look at the world as finite, and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible, and humans as wily managers of the planet. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as our future and our goal. Wizards regard Earth as a toolbox, its contents freely available for use; Prophets think of the natural world as embodying an overarching order that should not casually be disturbed.

Thanos is a prophet and the Avengers are wizards…both are even specifically referred to using those exact words at different points in the movie. More specifically, Thanos is a Malthusian…he wants to cut the population of the galaxy in half to up everyone’s quality of life. From the book, a description of economist Thomas Malthus’ ideas:

Human populations will reproduce beyond their means of subsistence unless they are held back by practices like celibacy, late marriage, or birth control. But the reproductive urge is so strong that people at some point will stop restricting births and have children willy-nilly. When this happens, populations inevitably grow too large to feed. Then disease, famine, or war step in and brutally reduce human numbers until they are again in balance with their means of subsistence — at which stage they will increase again, beginning the unhappy cycle anew.

Jeremy Keith noticed the same thing and I echo his amazement: “I was not expecting to be confronted with the wizards vs. prophets debate while watching Avengers: Infinity War”.

A couple of weeks ago, I finished Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet. Normally I shy away from terms like “must-read” or “important” when talking about books, but I’m making an exception for this one. The Wizard and the Prophet is an important book, and I urge you to read it. (The chapter on climate change, including its fascinating history, is alone worth the effort.)

Mann is the author of 1491 and 1493 (both excellent, particularly 1491, which is one of my favorite nonfiction books ever) and I’ve been thinking of this one as the natural third part of a trilogy — it easily could have been called 2092. The Wizard and the Prophet is about two “dueling visions” of how humanity can provide food, energy, housing, and the pursuit of happiness to an estimated population of 10 billion in 2050 and beyond. According to Mann, this struggle is exemplified by two men: William Vogt and Norman Bourlag. The book, in a nutshell:

Vogt, born in 1902, laid out the basic ideas for the modern environmental movement. In particular, he founded what the Hampshire College demographer Betsy Hartmann has called “apocalyptic environmentalism” — the belief that unless humankind drastically reduces consumption its growing numbers and appetite will overwhelm the planet’s ecosystems. In best-selling books and powerful speeches, Vogt argued that affluence is not our greatest achievement but our biggest problem. Our prosperity is temporary, he said, because it is based on taking more from Earth than it can give. If we continue, the unavoidable result will be devastation on a global scale, perhaps including our extinction. Cut back! Cut back! was his mantra. Otherwise everyone will lose!

Borlaug, born twelve years later, has become the emblem of what has been termed “techno-optimism” or “cornucopianism” — the view that science and technology, properly applied, can help us produce our way out of our predicament. Exemplifying this idea, Borlaug was the primary figure in the research that in the 1960s created the “Green Revolution,” the combination of high-yielding crop varieties and agronomic techniques that raised grain harvests around the world, helping to avert tens of millions of deaths from hunger. To Borlaug, affluence was not the problem but the solution. Only by getting richer, smarter, and more knowledgeable can humankind create the science that will resolve our environmental dilemmas. Innovate! Innovate! was Borlaug’s cry. Only in that way can everyone win!

Or put more succinctly:

Prophets look at the world as finite, and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible, and humans as wily managers of the planet. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as our future and our goal. Wizards regard Earth as a toolbox, its contents freely available for use; Prophets think of the natural world as embodying an overarching order that should not casually be disturbed.

To combat climate change, should we stop flying (as meteorologist Eric Holthaus has urged) & switch to renewable energy or should we capture carbon from coal plants & build nuclear power plants? GMO crops or community-based organic farming? How can 10 billion people be happy and prosperous without ruining the planet?

I came to this book with an open mind, and came away far more informed about the debate but even more unsure about the way forward. The book offers no easy answers — it’s difficult to tell where Mann himself stands on the wizard/prophet continuum (although I would suspect more wizard than prophet, which is likely my leaning as well) — but it does ask many of the right questions. Wizards can order the book from Amazon while Prophets should seek it out at their local bookstore or library.

Further reading: an interview with Mann in Grist; Can Planet Earth Feed 10 Billion People?, an Atlantic article by Mann; The Edge of the Petri Dish, a piece by Mann in The Breakthrough; State of the Species, a 2012 piece by Mann that was an early attempt at W vs P; and The Wizard and the Prophet: On Steven Pinker and Yuval Noah Harari.

Last week Charles C. Mann, author of the excellent 1491 (one of my favorite nonfiction books ever) and 1493, tweeted what looked like a completed manuscript of a new book, The Wizard and the Prophet. Aside from a pub date (Oct 5), Mann was coy about details in the thread and there’s not a lot of information about the book on the internet. But there is a little. From the Books on Tape website:

From the best-selling, award-winning author of 1491 and 1493 — an incisive portrait of the two little-known twentieth-century scientists, Norman Borlaug and William Vogt, whose diametrically opposed views shaped our ideas about the environment, laying the groundwork for how people in the twenty-first century will choose to live in tomorrow’s world.

In forty years, Earth’s population will reach ten billion. Can our world support that? What kind of world will it be? Those answering these questions generally fall into two deeply divided groups — Wizards and Prophets, as Charles Mann calls them in this balanced, authoritative, non-polemical new book. The Prophets, he explains, follow William Vogt, a founding environmentalist who believed that in using more than our planet has to give, our prosperity will lead us to ruin. Cut back! was his mantra. Otherwise everyone will lose! The Wizards are the heirs of Norman Borlaug, whose research, in effect, wrangled the world in service to our species to produce modern high-yield crops that then saved millions from starvation. Innovate! was Borlaug’s cry. Only in that way can everyone win! Mann delves into these diverging viewpoints to assess the four great challenges humanity faces — food, water, energy, climate change — grounding each in historical context and weighing the options for the future. With our civilization on the line, the author’s insightful analysis is an essential addition to the urgent conversation about how our children will fare on an increasingly crowded Earth.

In 2012, Orion Magazine published a piece by Mann called State of the Species, which was nominated for a 2013 National Magazine Award and is said to be “an early version of the introductory chapter” to The Wizard and the Prophet.

How can we provide these things for all these new people? That is only part of the question. The full question is: How can we provide them without wrecking the natural systems on which all depend?

Scientists, activists, and politicians have proposed many solutions, each from a different ideological and moral perspective. Some argue that we must drastically throttle industrial civilization. (Stop energy-intensive, chemical-based farming today! Eliminate fossil fuels to halt climate change!) Others claim that only intense exploitation of scientific knowledge can save us. (Plant super-productive, genetically modified crops now! Switch to nuclear power to halt climate change!) No matter which course is chosen, though, it will require radical, large-scale transformations in the human enterprise — a daunting, hideously expensive task.

Worse, the ship is too large to turn quickly. The world’s food supply cannot be decoupled rapidly from industrial agriculture, if that is seen as the answer. Aquifers cannot be recharged with a snap of the fingers. If the high-tech route is chosen, genetically modified crops cannot be bred and tested overnight. Similarly, carbon-sequestration techniques and nuclear power plants cannot be deployed instantly. Changes must be planned and executed decades in advance of the usual signals of crisis, but that’s like asking healthy, happy sixteen-year-olds to write living wills.

I’m very eager to tear into this book. The Prophets vs. The Wizards debate lies at the heart of issues about economic equality, climate change, and the future of energy (both electrical and nutritional). I see people having some form of this debate on Twitter every day, whether it’s about GMO crops, nuclear power, animal extinction, or carbon offsets.

Four years ago, Bill Gates, a Wizard to the core, talked to a small group of media about his most recent annual letter. I can’t recall exactly what Gates said — something like “you can’t tell a billion Indians they can’t have flatscreen TVs”1 — but I do remember very clearly how emphatically he stated that the way forward was not about the world cutting back on energy usage or consumption or less intensive farming. I think about his statement several times a week. I was unconvinced of his assertion at the time and still am. But my skepticism bothers me…I’m skeptical of my skepticism. Technology and progress have done a lot of good for the world — let’s talk infant mortality and infectious diseases for starters — but I am also sympathetic to the argument that the Agricultural Revolution was “history’s biggest fraud”. So yeah, I’m keen to see what Mann adds to this debate.

Update: The Wizard and the Prophet is now available for pre-order.

Stay Connected