kottke.org posts about Charles Mann

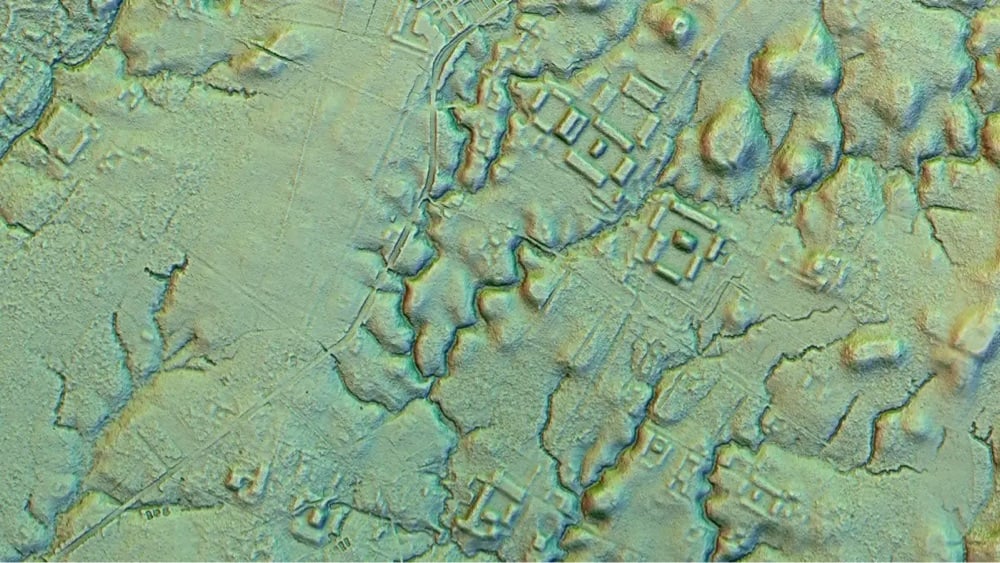

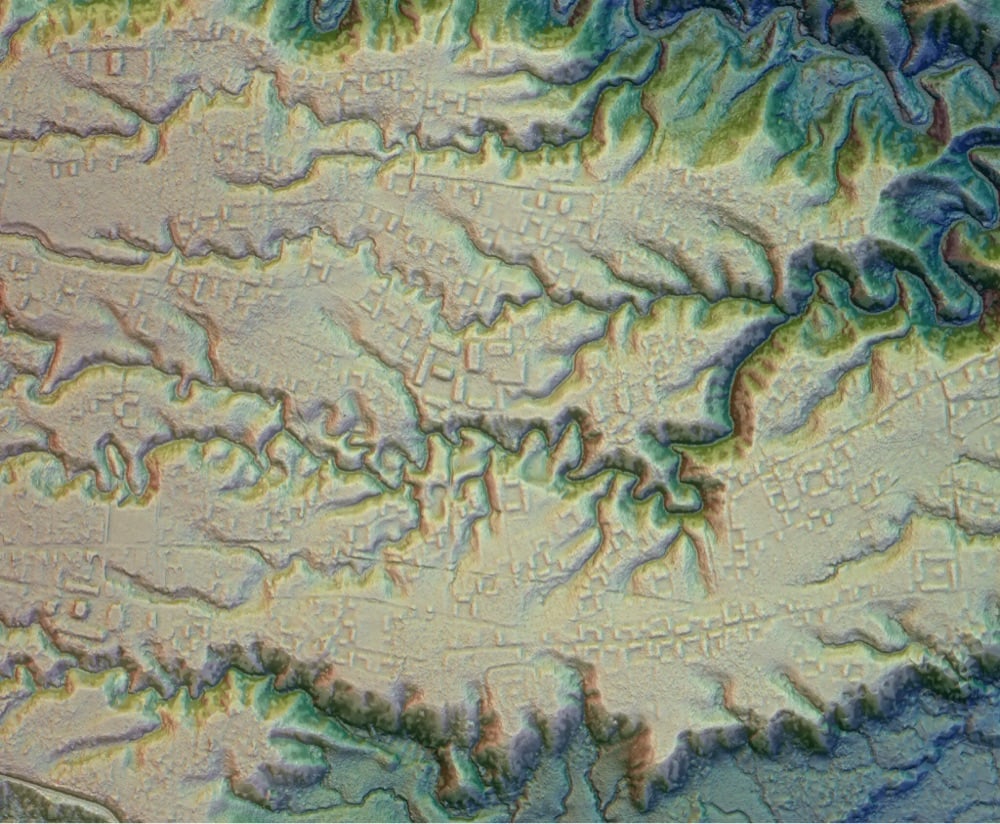

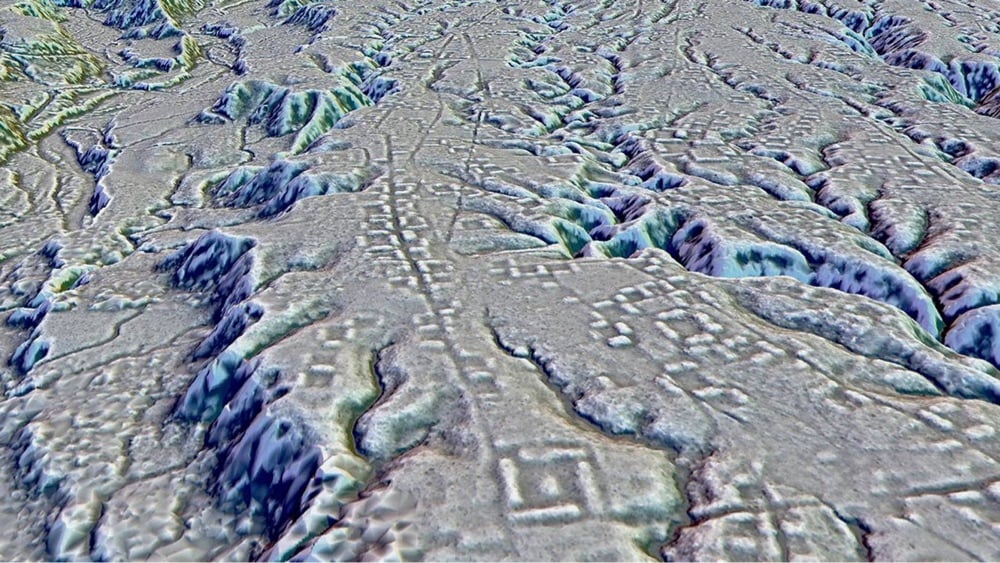

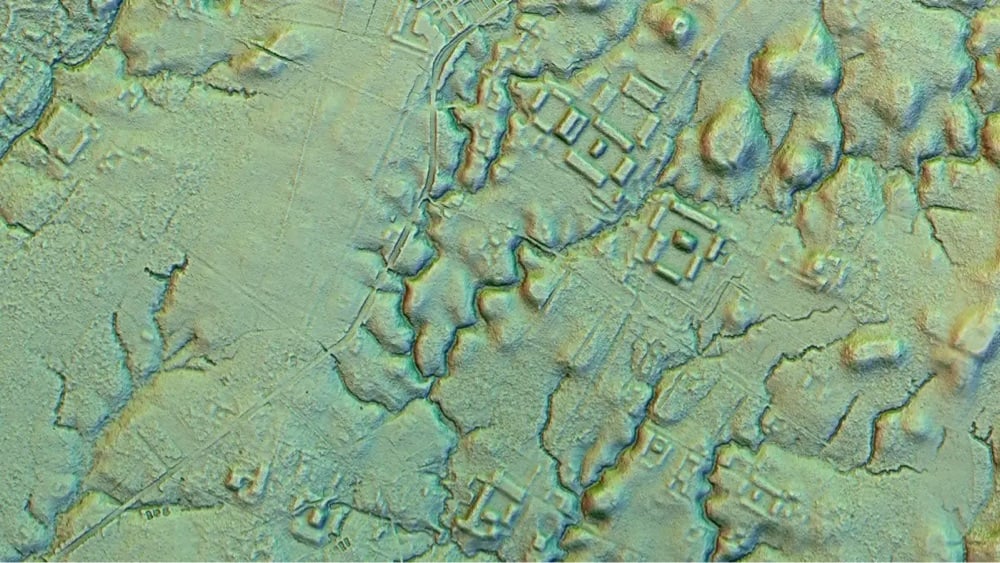

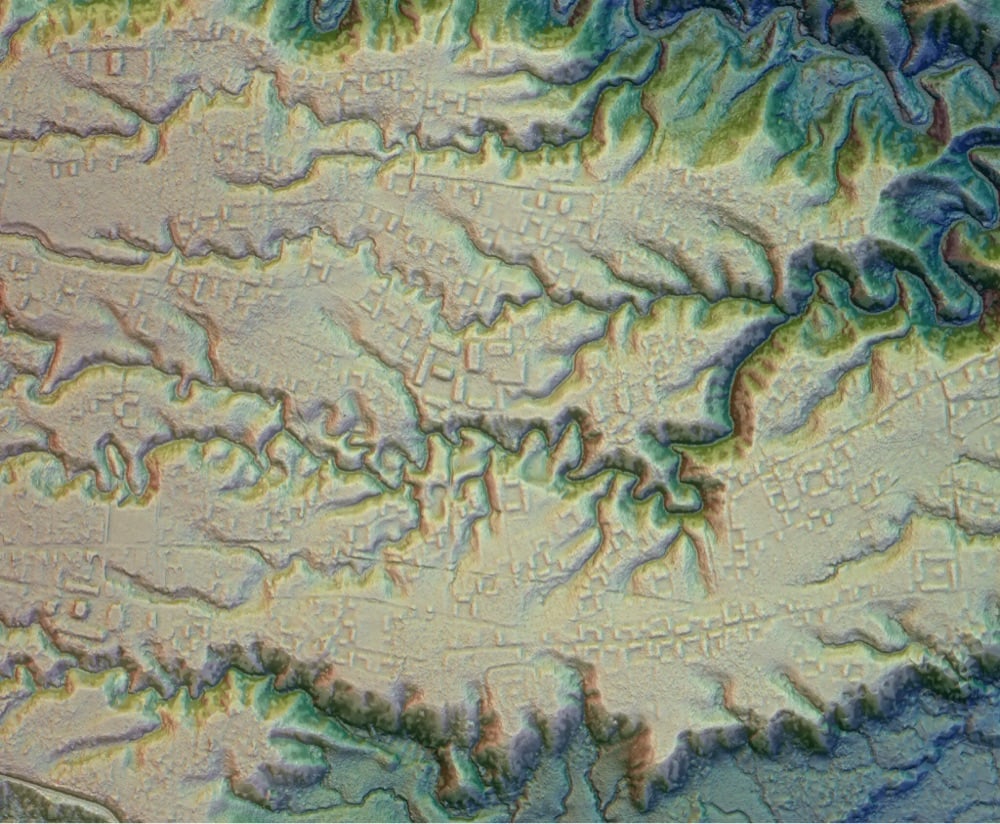

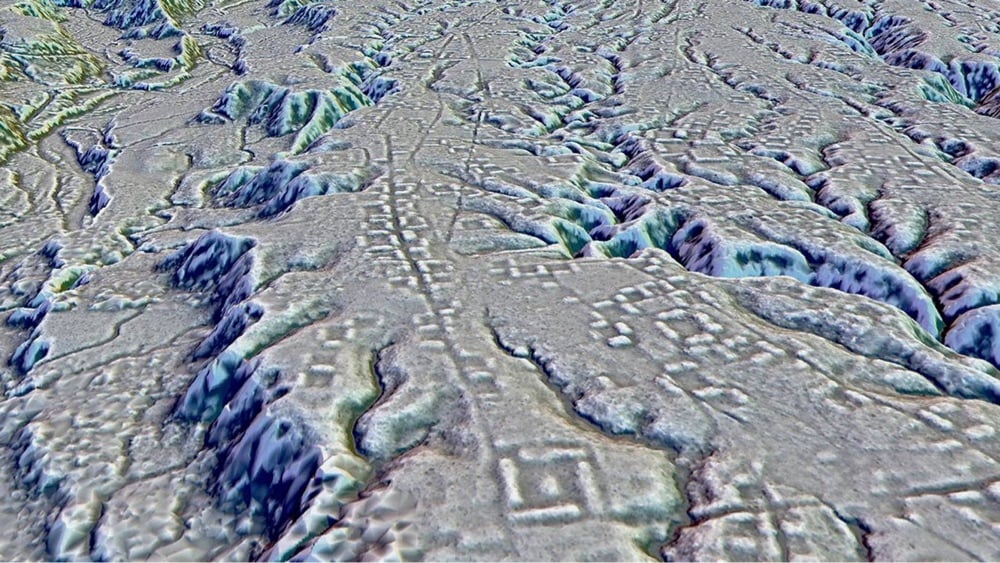

Using lidar, a team led by archaeologist Stéphen Rostain has found evidence of a network of cities in the Amazon dating back thousands of years. From the BBC:

Using airborne laser-scanning technology (Lidar), Rostain and his colleagues discovered a long-lost network of cities extending across 300sq km in the Ecuadorean Amazon, complete with plazas, ceremonial sites, drainage canals and roads that were built 2,500 years ago and had remained hidden for thousands of years. They also identified more than 6,000 rectangular earthen platforms believed to be homes and communal buildings in 15 urban centres surrounded by terraced agricultural fields.

The area may have been home to anywhere from 30,000 to hundreds of thousands of people:

“This discovery has proven there was an equivalent of Rome in Amazonia,” Rostain said. “The people living in these societies weren’t semi-nomadic people lost in the rainforest looking for food. They weren’t the small tribes of the Amazon we know today. They were highly specialised people: earthmovers, engineers, farmers, fishermen, priests, chiefs or kings. It was a stratified society, a specialised society, so there is certainly something of Rome.”

You can read more coverage of this in New Scientist, the NY Times, Science, and the Guardian.

I still remember reading Charles Mann’s Earthmovers of the Amazon (which he turned into the excellent 1491) almost 25 years ago and being astounded to learn that civilizations in the Americas were older, larger, and more widespread than I’d been taught.

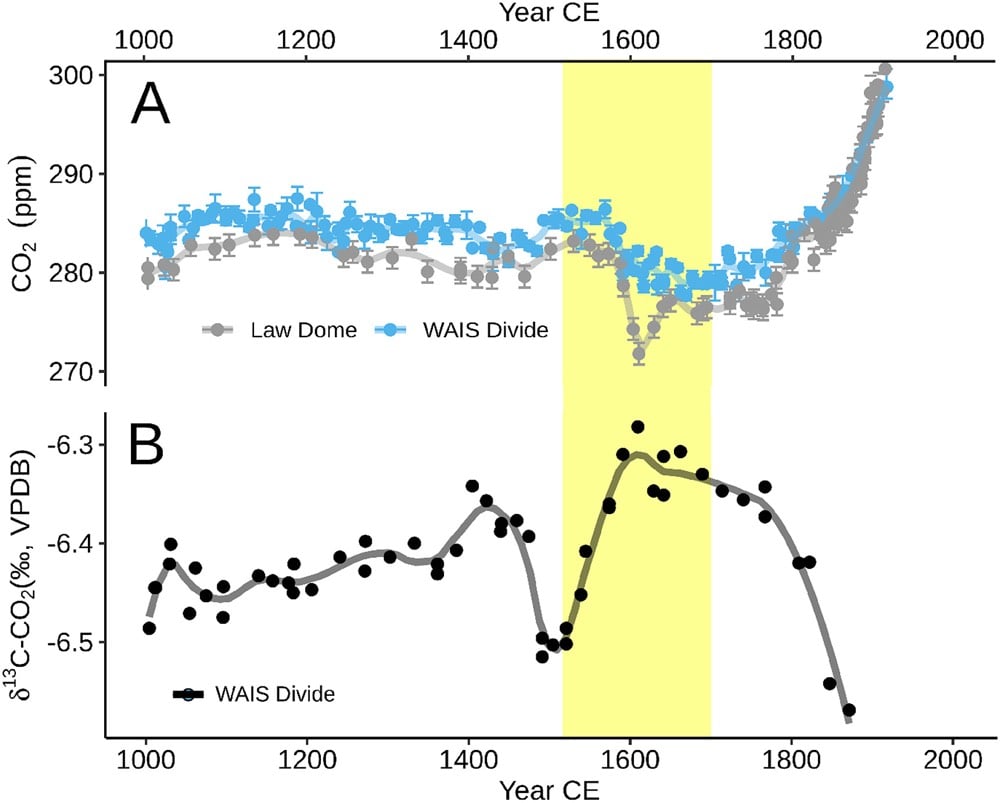

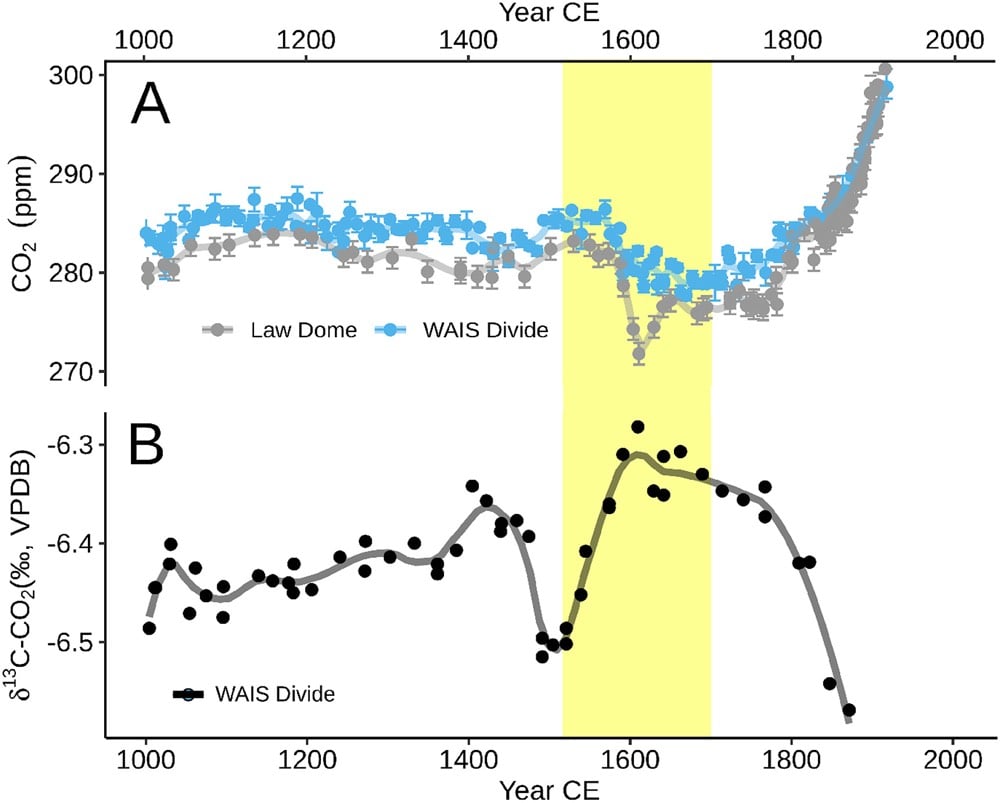

A new paper from researchers at University College London argues that the genocide of indigenous peoples in the Americans after Columbus’s landing in 1492 had a significant effect on the Earth’s global climate and was a major cause of the Little Ice Age, the dip in global temperatures from the 16th to the 19th centuries. They estimate that 55 million indigenous people died during Europe’s conquest of the Americas (~90% of the population), and the 56 million hectares of land that they had cleared of vegetation (roughly the area of Kenya) was then reclaimed by forests, which then took in more carbon dioxide, reduced the greenhouse effect, and caused the Earth to cool. From the paper’s conclusion:

We calculate that this led to an additional 7.4 Pg C being removed from the atmosphere and stored on the land surface in the 1500s. This was a change from the 1400s of 9.9 Pg C (5 ppm CO2). Including feedback processes this contributed between 47% and 67% of the 15-22 Pg C (7-10 ppm CO2) decline in atmospheric CO2 between 1520 CE and 1610 CE seen in Antarctic ice core records. These changes show that the Great Dying of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas is necessary for a parsimonious explanation of the anomalous decrease in atmospheric CO2 at that time and the resulting decline in global surface air temperatures.

The authors also assert that this effect of human action on global climate marks the beginning of the Anthropocene epoch.

I first heard about this theory from Charles Mann’s excellent 1493, which led me to William Ruddiman’s 2003 paper. I heard about this most recent study from Mann too… he called it “most careful study of the impacts of Euro conquest of Americas I’ve yet seen”.

If you’re not up for reading the paper itself, you can check out the coverage from the BBC, the Guardian, Nature, or the NY Times.

Last week, I was under the rock that everyone talks about and didn’t get to see Avengers: Infinity War until a couple of days ago. (Mild spoilers follow.) There’s a lot to like about the movie — I personally loved watching it — but the thing that surprised the hell out of me was how closely the motivations of Thanos and the Avengers echoed the subject of Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet.

Prophets look at the world as finite, and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible, and humans as wily managers of the planet. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as our future and our goal. Wizards regard Earth as a toolbox, its contents freely available for use; Prophets think of the natural world as embodying an overarching order that should not casually be disturbed.

Thanos is a prophet and the Avengers are wizards…both are even specifically referred to using those exact words at different points in the movie. More specifically, Thanos is a Malthusian…he wants to cut the population of the galaxy in half to up everyone’s quality of life. From the book, a description of economist Thomas Malthus’ ideas:

Human populations will reproduce beyond their means of subsistence unless they are held back by practices like celibacy, late marriage, or birth control. But the reproductive urge is so strong that people at some point will stop restricting births and have children willy-nilly. When this happens, populations inevitably grow too large to feed. Then disease, famine, or war step in and brutally reduce human numbers until they are again in balance with their means of subsistence — at which stage they will increase again, beginning the unhappy cycle anew.

Jeremy Keith noticed the same thing and I echo his amazement: “I was not expecting to be confronted with the wizards vs. prophets debate while watching Avengers: Infinity War”.

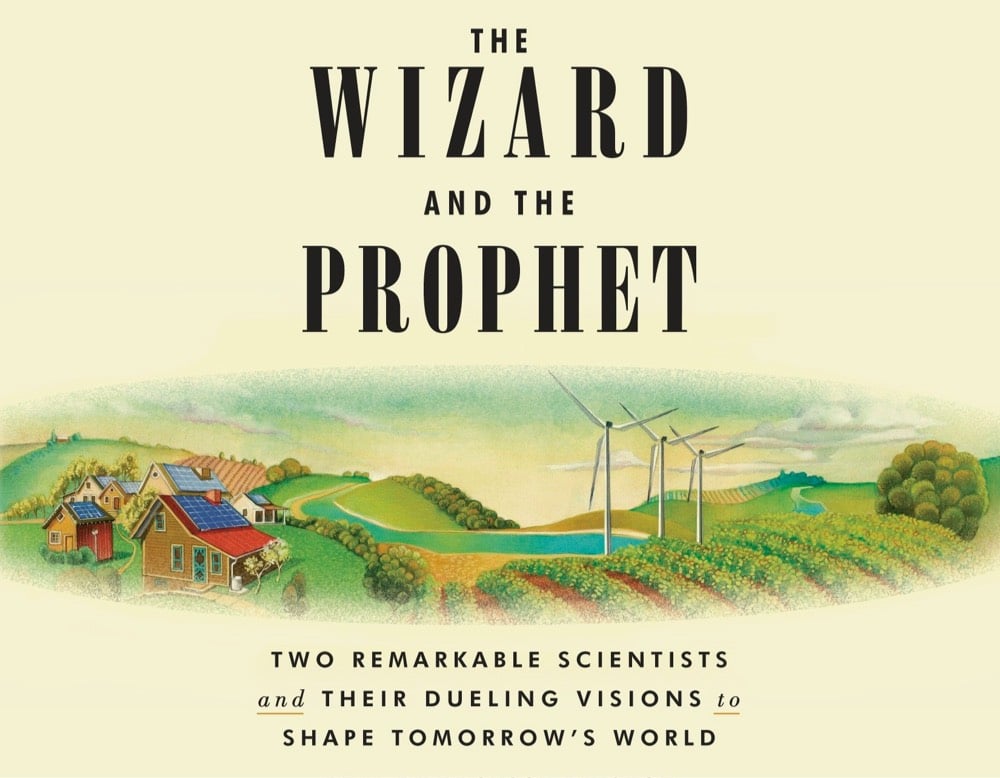

A couple of weeks ago, I finished Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet. Normally I shy away from terms like “must-read” or “important” when talking about books, but I’m making an exception for this one. The Wizard and the Prophet is an important book, and I urge you to read it. (The chapter on climate change, including its fascinating history, is alone worth the effort.)

Mann is the author of 1491 and 1493 (both excellent, particularly 1491, which is one of my favorite nonfiction books ever) and I’ve been thinking of this one as the natural third part of a trilogy — it easily could have been called 2092. The Wizard and the Prophet is about two “dueling visions” of how humanity can provide food, energy, housing, and the pursuit of happiness to an estimated population of 10 billion in 2050 and beyond. According to Mann, this struggle is exemplified by two men: William Vogt and Norman Bourlag. The book, in a nutshell:

Vogt, born in 1902, laid out the basic ideas for the modern environmental movement. In particular, he founded what the Hampshire College demographer Betsy Hartmann has called “apocalyptic environmentalism” — the belief that unless humankind drastically reduces consumption its growing numbers and appetite will overwhelm the planet’s ecosystems. In best-selling books and powerful speeches, Vogt argued that affluence is not our greatest achievement but our biggest problem. Our prosperity is temporary, he said, because it is based on taking more from Earth than it can give. If we continue, the unavoidable result will be devastation on a global scale, perhaps including our extinction. Cut back! Cut back! was his mantra. Otherwise everyone will lose!

Borlaug, born twelve years later, has become the emblem of what has been termed “techno-optimism” or “cornucopianism” — the view that science and technology, properly applied, can help us produce our way out of our predicament. Exemplifying this idea, Borlaug was the primary figure in the research that in the 1960s created the “Green Revolution,” the combination of high-yielding crop varieties and agronomic techniques that raised grain harvests around the world, helping to avert tens of millions of deaths from hunger. To Borlaug, affluence was not the problem but the solution. Only by getting richer, smarter, and more knowledgeable can humankind create the science that will resolve our environmental dilemmas. Innovate! Innovate! was Borlaug’s cry. Only in that way can everyone win!

Or put more succinctly:

Prophets look at the world as finite, and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible, and humans as wily managers of the planet. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as our future and our goal. Wizards regard Earth as a toolbox, its contents freely available for use; Prophets think of the natural world as embodying an overarching order that should not casually be disturbed.

To combat climate change, should we stop flying (as meteorologist Eric Holthaus has urged) & switch to renewable energy or should we capture carbon from coal plants & build nuclear power plants? GMO crops or community-based organic farming? How can 10 billion people be happy and prosperous without ruining the planet?

I came to this book with an open mind, and came away far more informed about the debate but even more unsure about the way forward. The book offers no easy answers — it’s difficult to tell where Mann himself stands on the wizard/prophet continuum (although I would suspect more wizard than prophet, which is likely my leaning as well) — but it does ask many of the right questions. Wizards can order the book from Amazon while Prophets should seek it out at their local bookstore or library.

Further reading: an interview with Mann in Grist; Can Planet Earth Feed 10 Billion People?, an Atlantic article by Mann; The Edge of the Petri Dish, a piece by Mann in The Breakthrough; State of the Species, a 2012 piece by Mann that was an early attempt at W vs P; and The Wizard and the Prophet: On Steven Pinker and Yuval Noah Harari.

Last week Charles C. Mann, author of the excellent 1491 (one of my favorite nonfiction books ever) and 1493, tweeted what looked like a completed manuscript of a new book, The Wizard and the Prophet. Aside from a pub date (Oct 5), Mann was coy about details in the thread and there’s not a lot of information about the book on the internet. But there is a little. From the Books on Tape website:

From the best-selling, award-winning author of 1491 and 1493 — an incisive portrait of the two little-known twentieth-century scientists, Norman Borlaug and William Vogt, whose diametrically opposed views shaped our ideas about the environment, laying the groundwork for how people in the twenty-first century will choose to live in tomorrow’s world.

In forty years, Earth’s population will reach ten billion. Can our world support that? What kind of world will it be? Those answering these questions generally fall into two deeply divided groups — Wizards and Prophets, as Charles Mann calls them in this balanced, authoritative, non-polemical new book. The Prophets, he explains, follow William Vogt, a founding environmentalist who believed that in using more than our planet has to give, our prosperity will lead us to ruin. Cut back! was his mantra. Otherwise everyone will lose! The Wizards are the heirs of Norman Borlaug, whose research, in effect, wrangled the world in service to our species to produce modern high-yield crops that then saved millions from starvation. Innovate! was Borlaug’s cry. Only in that way can everyone win! Mann delves into these diverging viewpoints to assess the four great challenges humanity faces — food, water, energy, climate change — grounding each in historical context and weighing the options for the future. With our civilization on the line, the author’s insightful analysis is an essential addition to the urgent conversation about how our children will fare on an increasingly crowded Earth.

In 2012, Orion Magazine published a piece by Mann called State of the Species, which was nominated for a 2013 National Magazine Award and is said to be “an early version of the introductory chapter” to The Wizard and the Prophet.

How can we provide these things for all these new people? That is only part of the question. The full question is: How can we provide them without wrecking the natural systems on which all depend?

Scientists, activists, and politicians have proposed many solutions, each from a different ideological and moral perspective. Some argue that we must drastically throttle industrial civilization. (Stop energy-intensive, chemical-based farming today! Eliminate fossil fuels to halt climate change!) Others claim that only intense exploitation of scientific knowledge can save us. (Plant super-productive, genetically modified crops now! Switch to nuclear power to halt climate change!) No matter which course is chosen, though, it will require radical, large-scale transformations in the human enterprise — a daunting, hideously expensive task.

Worse, the ship is too large to turn quickly. The world’s food supply cannot be decoupled rapidly from industrial agriculture, if that is seen as the answer. Aquifers cannot be recharged with a snap of the fingers. If the high-tech route is chosen, genetically modified crops cannot be bred and tested overnight. Similarly, carbon-sequestration techniques and nuclear power plants cannot be deployed instantly. Changes must be planned and executed decades in advance of the usual signals of crisis, but that’s like asking healthy, happy sixteen-year-olds to write living wills.

I’m very eager to tear into this book. The Prophets vs. The Wizards debate lies at the heart of issues about economic equality, climate change, and the future of energy (both electrical and nutritional). I see people having some form of this debate on Twitter every day, whether it’s about GMO crops, nuclear power, animal extinction, or carbon offsets.

Four years ago, Bill Gates, a Wizard to the core, talked to a small group of media about his most recent annual letter. I can’t recall exactly what Gates said — something like “you can’t tell a billion Indians they can’t have flatscreen TVs”1 — but I do remember very clearly how emphatically he stated that the way forward was not about the world cutting back on energy usage or consumption or less intensive farming. I think about his statement several times a week. I was unconvinced of his assertion at the time and still am. But my skepticism bothers me…I’m skeptical of my skepticism. Technology and progress have done a lot of good for the world — let’s talk infant mortality and infectious diseases for starters — but I am also sympathetic to the argument that the Agricultural Revolution was “history’s biggest fraud”. So yeah, I’m keen to see what Mann adds to this debate.

Update: The Wizard and the Prophet is now available for pre-order.

Research on an arrangement of massive granite blocks in the Brazilian Amazon has indicated that they were used as an astronomical observatory about 1000 years ago.

After conducting radiocarbon testing and carrying out measurements during the winter solstice, scholars in the field of archaeoastronomy determined that an indigenous culture arranged the megaliths into an astronomical observatory about 1,000 years ago, or five centuries before the European conquest of the Americas began.

Their findings, along with other archaeological discoveries in Brazil in recent years — including giant land carvings, remains of fortified settlements and even complex road networks — are upending earlier views of archaeologists who argued that the Amazon had been relatively untouched by humans except for small, nomadic tribes.

I still remember reading Charles Mann’s piece in 2002 about the mounting evidence against the idea of a largely wild and pristine pair of continents civilized and tamed by Europeans.

Erickson and Balée belong to a cohort of scholars that has radically challenged conventional notions of what the Western Hemisphere was like before Columbus. When I went to high school, in the 1970s, I was taught that Indians came to the Americas across the Bering Strait about 12,000 years ago, that they lived for the most part in small, isolated groups, and that they had so little impact on their environment that even after millennia of habitation it remained mostly wilderness. My son picked up the same ideas at his schools. One way to summarize the views of people like Erickson and Balée would be to say that in their opinion this picture of Indian life is wrong in almost every aspect. Indians were here far longer than previously thought, these researchers believe, and in much greater numbers. And they were so successful at imposing their will on the landscape that in 1492 Columbus set foot in a hemisphere thoroughly dominated by humankind.

That article turned into 1491, which remains one of my favorite books.

See also Ars Technica’s recent piece Finding North America’s lost medieval city.

Charles Mann’s 1491 is one of my all-time favorite books. I mean, if this description doesn’t stir you:

Contrary to what so many Americans learn in school, the pre-Columbian Indians were not sparsely settled in a pristine wilderness; rather, there were huge numbers of Indians who actively molded and influenced the land around them. The astonishing Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had running water and immaculately clean streets, and was larger than any contemporary European city. Mexican cultures created corn in a specialized breeding process that it has been called man’s first feat of genetic engineering. Indeed, Indians were not living lightly on the land but were landscaping and manipulating their world in ways that we are only now beginning to understand. Challenging and surprising, this a transformative new look at a rich and fascinating world we only thought we knew.

On Twitter yesterday, Mann shared that a documentary series was being made based on the book. The eight-part series is being commissioned by Canada’s APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network) and Barbara Hager, who is of Cree/Metis heritage, will write, direct, and produce.

This is fantastic news. I hope this gets US distribution at some point, even if it’s online-only.

One of the major points in Charles Mann’s 1491 (great book, a fave) is that the indigenous peoples of the Americas did not live in pristine wilderness. Through techniques like cultivation and controlled burning, they profoundly shaped their environments, from the forests of New England to the Amazon.

In the 1850s, the indigenous inhabitants of Yosemite Valley, who used controlled burning to maintain the health of the forest, were driven out by a militia. As Eric Michael Johnson writes in Scientific American, the belief in the myth of pristine wilderness by naturalist John Muir has had a negative impact on the biodiversity and the ability to prevent catastrophic fire damage in Yosemite National Park.

The results of this analysis were statistically significant (p < 0.01) and revealed that shade-tolerant species such as White fir and incense cedar had increased to such an extent that Yosemite Valley was now two times more densely packed than it had been in the nineteenth century. These smaller and more flammable trees had pushed out the shade-intolerant species, such as oak or pine, and reduced their numbers by half. After a century of fire suppression in the Yosemite Valley biodiversity had actually declined, trees were now 20 percent smaller, and the forest was more vulnerable to catastrophic fires than it had been before the U.S. Army and armed vigilantes expelled the native population.

(via @charlescmann)

You have solar on your roof, a hybrid in your garage, and wind, water, nuclear, and natural gas all being pushed by various companies and interest groups. But, now, and for the foreseeable future, you’ve also got coal. And lots of it. Wired’s Charles C. Mann lays it out:

A lump of coal is a thoroughly ubiquitous 21st-century artifact, as much an emblem of our time as the iPhone. Today coal produces more than 40 percent of the world’s electricity, a foundation of modern life. And that percentage is going up.

That reality is bad news for the environment and climate change, and it leaves us with a big question: How do we minimize the damage?

As a belated recognition of Exploration Day, here’s Charles C. Mann’s piece on the history of the Americas before Columbus: 1491. This piece blew my doors off when I first read it.

Before it became the New World, the Western Hemisphere was vastly more populous and sophisticated than has been thought-an altogether more salubrious place to live at the time than, say, Europe. New evidence of both the extent of the population and its agricultural advancement leads to a remarkable conjecture: the Amazon rain forest may be largely a human artifact.

This article spawned a book of the same name, which is one of my favorite non-fiction reads of the past decade.

Writing for The Atlantic, Charles C. Mann writes about a little-exploited fossil fuel called methane hydrate (“crystalline natural gas”) that is present in the Earth’s crust in great quantities…”by some estimates, it is twice as abundant as all other fossil fuels combined”.

If methane hydrate allows much of the world to switch from oil to gas, the conversion would undermine governments that depend on oil revenues, especially petro-autocracies like Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. Unless oil states are exceptionally well run, a gush of petroleum revenues can actually weaken their economies by crowding out other business. Worse, most oil nations are so corrupt that social scientists argue over whether there is an inherent bond-a “resource curse”-between big petroleum deposits and political malfeasance. It seems safe to say that few Americans would be upset if a plunge in demand eliminated these countries’ hold over the U.S. economy. But those same people might not relish the global instability — a belt of financial and political turmoil from Venezuela to Turkmenistan — that their collapse could well unleash.

On a broader level still, cheap, plentiful natural gas throws a wrench into efforts to combat climate change. Avoiding the worst effects of climate change, scientists increasingly believe, will require “a complete phase-out of carbon emissions… over 50 years,” in the words of one widely touted scientific estimate that appeared in January. A big, necessary step toward that goal is moving away from coal, still the second-most-important energy source worldwide. Natural gas burns so much cleaner than coal that converting power plants from coal to gas-a switch promoted by the deluge of gas from fracking-has already reduced U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions to their lowest levels since Newt Gingrich’s heyday.

We’ve spent the two dozen years putting computers in everything from our bodies to our cars. Now those devices increasingly have wireless connections to the outside world. Throw in a little lax security and the whole world becomes hackable.

Hospital equipment like external defibrillators and fetal monitors can at least be picked up, taken apart, or carted away. Implanted devices — equipment surgically implanted into the body — are vastly more difficult to remove but not all that much harder to attack.

You don’t even have to know anything about medical devices’ software to attack them remotely, Fu says. You simply have to call them repeatedly, waking them up so many times that they exhaust their batteries-a medical version of the online “denial of service” attack, in which botnets overwhelm Web sites with millions of phony messages. On a more complex level, pacemaker-subverter Barnaby Jack has been developing Electric Feel, software that scans for medical devices in crowds, compromising all within range. Although Jack emphasizes that Electric Feel “was created for research purposes, in the wrong hands it could have deadly consequences.” (A General Accounting Office report noted in August that Uncle Sam had never systematically analyzed medical devices for their hackability, and recommended that the F.D.A. take action.)

Charles Mann visits the airport with security expert Bruce Schneier and a fake boarding pass. What he finds is a lot of security theater and not much security.

“The only useful airport security measures since 9/11,” he says, “were locking and reinforcing the cockpit doors, so terrorists can’t break in, positive baggage matching” — ensuring that people can’t put luggage on planes, and then not board them — “and teaching the passengers to fight back. The rest is security theater.”

(via df)

In recent years, authors have claimed that many seemingly boring things have changed the world but a particularly strong case can be made for the potato and Charles C. Mann makes it.

The effects of this transformation were so striking that any general history of Europe without an entry in its index for S. tuberosum should be ignored. Hunger was a familiar presence in 17th- and 18th-century Europe. Cities were provisioned reasonably well in most years, their granaries carefully monitored, but country people teetered on a precipice. France, the historian Fernand Braudel once calculated, had 40 nationwide famines between 1500 and 1800, more than one per decade. This appalling figure is an underestimate, he wrote, “because it omits the hundreds and hundreds of local famines.” France was not exceptional; England had 17 national and big regional famines between 1523 and 1623. The continent simply could not reliably feed itself.

The potato changed all that. Every year, many farmers left fallow as much as half of their grain land, to rest the soil and fight weeds (which were plowed under in summer). Now smallholders could grow potatoes on the fallow land, controlling weeds by hoeing. Because potatoes were so productive, the effective result, in terms of calories, was to double Europe’s food supply.

Mann talks more about the potato in his excellent 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created.

I’m slowly working my way through Charles Mann’s 1493 and there are interesting tidbits on almost every page. One of my favorite bits of the book so far is a possible explanation of the Little Ice Age that I hadn’t heard before put forth by William Ruddiman.

As human communities grow, Ruddiman pointed out, they open more land for farms and cut down more trees for fuel and shelter. In Europe and Asia, forests were cut down with the ax. In the Americas before [Columbus], the primary tool was fire. For weeks on end, smoke from Indian bonfires shrouded Florida, California, and the Great Plains.

Burning like this happened all over the pre-Columbian Americas, from present-day New England to Mexico to the Amazon basin to Argentina. Then the Europeans came:

Enter now the Columbian Exchange. Eurasian bacteria, viruses, and parasites sweep through the Americas, killing huge numbers of people — and unraveling the millenia-old network of human intervention. Flames subside to embers across the Western Hemisphere as Indian torches are stilled. In the forests, fire-hating trees like oak and hickory muscle aside fire-loving species like loblolly, longleaf, and slash pine, which are so dependent on regular burning that their cones will only open and release seed when exposed to flame. Animals that Indians had hunted, keeping their numbers down, suddenly flourish in great numbers. And so on.

The regular fires and forest regrowth resulted in less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the atmosphere traps less heat. It’s like global warming in reverse.

Tyler Cowen says that Charles Mann’s 1491 (a taste of which can be read here) is “one of my favorite books ever, in any field”, to which I add a hearty “me too”. Mann’s been hard at work at a sequel, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, which is due out in August, just in time for some seriously awesome beach reading.

From the author of 1491 — the best-selling study of the pre-Columbian Americas — a deeply engaging new history that explores the most momentous biological event since the death of the dinosaurs.

More than 200 million years ago, geological forces split apart the continents. Isolated from each other, the two halves of the world developed totally different suites of plants and animals. Columbus’s voyages brought them back together — and marked the beginning of an extraordinary exchange of flora and fauna between Eurasia and the Americas. As Charles Mann shows, this global ecological tumult — the “Columbian Exchange” — underlies much of subsequent human history. Presenting the latest generation of research by scientists, Mann shows how the creation of this worldwide network of exchange fostered the rise of Europe, devastated imperial China, convulsed Africa, and for two centuries made Manila and Mexico City — where Asia, Europe, and the new frontier of the Americas dynamically interacted — the center of the world.

Stay Connected