kottke.org posts about media

About five years ago, a funny thing happened: for birthdays and holidays, instead of LEGO sets or basketball jerseys, my son started asking me to buy him vinyl records. I happily complied: it was fun to mix new and old records together, track down semi-rare albums, and then listen to the music together, plus talk about music all the time.

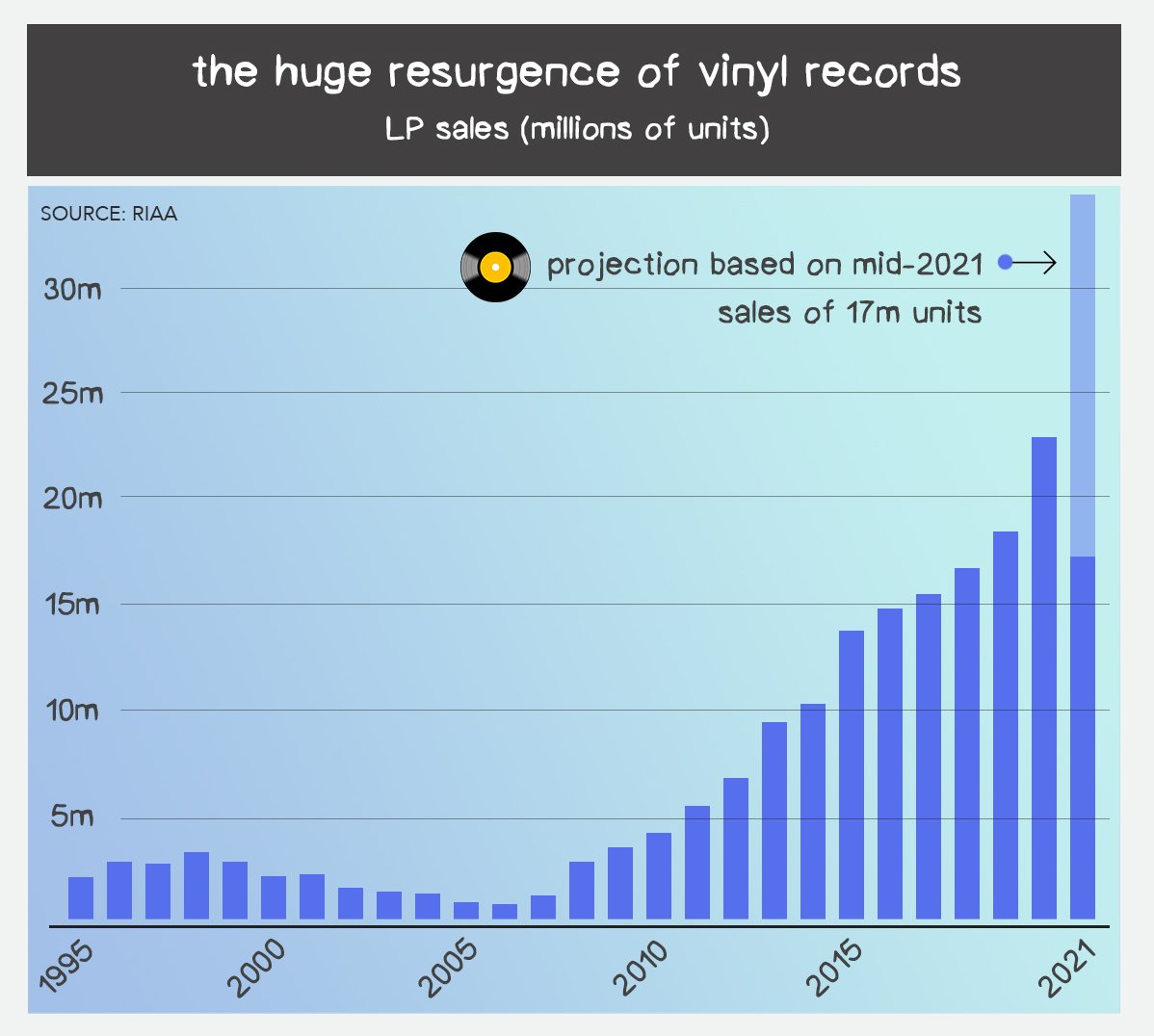

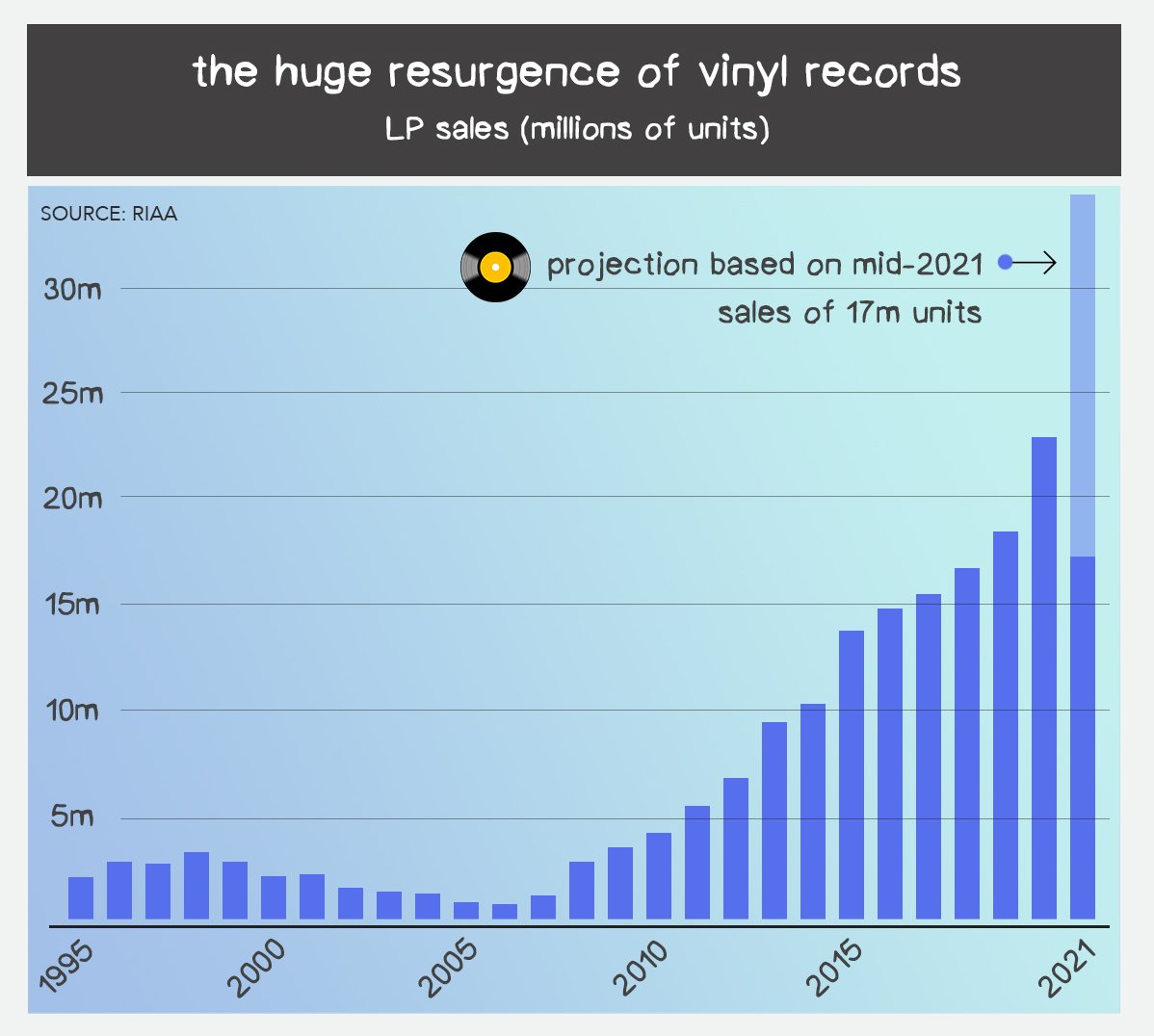

It turns out my teen wasn’t an outlier: younger people are buying vinyl at a rate not seen in over a generation, not just as collectors or as an affectation, but as a first-line way to enjoy music, new and old. What’s more, the revenue from vinyl sales was a small but substantial lifeline to artists squeezed by streaming’s stingy royalty rates.

At The Hustle, Zachary Crockett does the math:

For modern-day indie artists, it’s a welcome boom. A vinyl record costs ~$7 to manufacture, and a band typically sells it directly to fans for $25, good for $18 in profit. By contrast, streaming services only pay out a fraction of a penny for each listen. A band would have to amass 450k streams on Spotify to match the profit of 100 vinyl sales.

There are also moments where the streaming and vinyl economy come together. Bandcamp has a vinyl pressing service, and some of the most popular music videos on YouTube are needle drop recordings of a fan playing a vinyl record.

There are some bottlenecks, though. First, streaming is a much bigger ocean than vinyl. Second, vinyl’s manufacturing capacity is greatly reduced from its heyday, making it more arduous and fragile to make, manufacture, and distribute a vinyl record. Finally, the environmental impacts of vinyl manufacturing aren’t great.

But the aesthetics — oh, the sweet joy of a needle on a record — the aesthetics can’t be beat.

Update: Crockett’s arithmetic above is a little hasty. For one thing, it doesn’t include shipping costs, which can either make a record much more expensive or cut into the profit margin. It’s definitely a better profit margin than streaming music royalties, but it is one where costs are at a premium.

Navneet Alang provides a good overview of the many ways in which the ever growing influence of various algorithms is transforming all forms of media, from motion smoothing, to “Spotify-core” music, to TikTok’s influence over length and memorable hooks.

The algorithmic delivery of music thus forms what, for Spotify, is a virtuous circle. But it also suggests that tech platforms don’t just deliver content, but that they shape it too, prioritizing quick hits and short tracks because those are the things that generate the most engagement.

Those platforms and their algorithms change not only the form of the content we consume but the way we consume it, like Netflix’s current test to allow speeding up of video playback, like some of us do when listening to podcasts.

Netflix is aware that people want to rush through content — not just to enjoy it, but also to then participate in the cultural conversation that’s around it. Is everyone at work talking about Succession, Fleabag, and that new true crime podcast, but you’re behind on all of them? Well, rip through them at double speed so you aren’t left out.

Alang argues that while we’ve always played around with how we read, view, or listen to art, we are now in front of something of a different magnitude.

But the sheer ubiquity of the streaming platforms for how we get content now suggests that the dominance of algorithms and their place in the attention economy aren’t entirely neutral or value-free. Disney, for example, is quietly placing classic Fox films into its so-called “vault,” where it hides movies from distribution for a while to drum up hype when they are re-released. One imagines this is so they can put them back on their forthcoming streaming service, to much delight.

Alas, as with so many things around the internet and “digital,” what was originally an opportunity for every little niche and taste to get its place in the sun, is instead being dumbed down into an “algorithmed” and business optimized mass of sameness.

Jeff Jarvis with some good comments (based primarily on a paper by Axel Bruns) arguing that the media in general needs to start with deeper questions, more research, referencing actual research, and demonstrable facts instead of presumptions. Excellent ideas.

He begins with this quote from the Bruns paper:

[T]hat echo chambers and filter bubbles principally constitute an unfounded moral panic that presents a convenient technological scapegoat (search and social platforms and their affordances and algorithms) for a much more critical problem: growing social and political polarisation. But this is a problem that has fundamentally social and societal causes, and therefore cannot be solved by technological means alone. [Emphasis mine.]

Agreed. Jarvis via Bruns then argues that these metaphors are too loosely defined, leaving room for broad usage, unclear meaning, resulting in moral panic more than actual research and fact based analysis.

He follows up with a number of articles and further research from the paper, backing up his point. Then numerous examples of media using the filter bubble shortcut. I encourage you to click through to the article and dive a bit deeper.

But that leads to another journalistic weakness in reporting academic studies: stories that takes the latest word as the last word.

Absolutely. And pretty much everyone does that at some point so it’s a good reminder to us all to consider new research and explanations of the day within broader historical context and preexisting knowledge.

The whole article (and the research paper, although I myself haven’t gotten to that yet) is worth a read, the main point of Jarvis is a good one; more questions, more research, deeper thinking. Looking at people and how they use the technology, not just the tech itself.

I do have to caveat this though by mentioning the Jarvis dismisses Shoshana Zuboff’s work on Surveillance Capitalism by portraying it as “an extreme name for advertising cookies and the use of the word devalues the seriousness of actual surveillance by governments.” One could debate whether Zuboff should have used another word, separating the practice from that of governments, but by saying “advertising cookies” Jarvis makes one of those surface remarks he raves against in his piece, somewhat discrediting it.

I recently had to put my Amazon newsletter, The Amazon Chronicles, on a two-month hiatus because I’m going to have surgery to replace my shoulder. So what should happen the day after I make my announcement? One of the very best Amazon reporters, Recode’s Jason Del Rey, comes out with an oral history of Amazon Prime, the membership program that covers free fast shipping, digital media, and more — and arguably, the innovation that pushed Amazon past eBay and Walmart to become the retailer of first resort.

Charlie Ward (former Amazon principal engineer; current Amazon VP, technology)

I’m a one-click addict. I hate having to go through the order pipeline and choose everything again and again and again. And … I couldn’t use one click with Super Saver Free Shipping.

I kind of have a perfectionist type of mentality. Things kind of irritate me and get more and more irritating over time and it was just really confirmed to me that I couldn’t make it better. So I threw out this problem to the group: “Wouldn’t it be great if customers just gave us a chunk of change at the beginning of the year and we calculated zero for their shipping charges the rest of that year?”

And we kind of had a small pause, a moment where we all looked at it as like, “Is Charlie crazy?”

See also this digital media pullquote which Peter Kafka pointed out on Twitter.

Bill Carr (former Amazon VP of digital music and video)

Netflix had a budget which — and you’re going to laugh when I tell you the scary number — was $35 million dollars a year on video content. These were fixed costs. This meant they’d go and buy the rights to movies and TV shows from the studios for $35 million a year and it didn’t matter whether they had one viewer or 100 million viewers, that’s what they’re going to pay. Well, that’s not the business Amazon was in.

We were giving much more than $35 million a year to the motion-picture studios at the time. But it was a daunting thing to commit to it on a fixed-fee basis with no knowledge of how we’re going to actually get any subscribers. In the 2008, ‘09, ‘10 era, that was a scary amount of money.

And I remember then Jeff finally goes, “I’ve got an idea.” And in typical Jeff fashion he picked something that was not on the list at all and he said, “Let’s make it part of Amazon Prime.” And we looked at him like there are arms and legs growing out of his head. Like, “What are you talking about? Amazon Prime? That’s the free shipping program.”

And the principle that Jeff realized was that we need to do actually exactly what Netflix did when they first launched their digital service. Everyone scoffed at that, too. Like, “you’re offering digital plus DVDs and you’re not charging more?”

Netflix was able to get away with the fact that the content was not great at the beginning because it was free. It was like, “Oh, by the way, here you go, here’s some movies along with it.” And we were going to take a page out of their book.

I remember Jeff used those exact words — It’s an, “Oh, by the way.” “Yeah, Prime is $79 a year. Oh, by the way, there’s free movies and TV shows with it.” And how much could consumers complain about the quality of movies and TV shows if it’s free?

Book trailers are already such a thing that there’s whole weekly columns devoted to them, a whole slew of tips and tricks; a veritable ecosystem. People want multimedia with their books. But what if the new hotness wasn’t a trailer at all? What if it was something that lots of us already do anyways, with a much lower barrier for entry?

I’m talking about book playlists, music that reflects the theme or the time and place of the book, a non-audiobook soundtrack that enhances and embellishes the written word. I love this idea!

Now, there are, as I see it, two ways to go with playlists period, and book playlists in particular. First, you can go big. Spotify and other music services can support hundreds of songs in individual playlists, and there’s no reason why you have to have just one. You can literally drown your reader/listener in sweet tunes to listen to while they read, to get psyched up while they’re waiting for their books to arrive, or to have a way to interact with the world of a book they might not even read or by.

This is the approach Questlove took when making a playlist for Michelle Obama’s blockbuster Becoming. It’s over a thousand songs split into three playlists, covering 1964 (Michelle’s birth year) to the present. Amazingly, as far as I can tell, there’s not a dud in the bunch. These selections are ridiculously good.

The other approach, which is a little more feasible for most of us, is to make a playlist about the length of an old mix CD — about 80 minutes, for those who don’t remember (and 60, 90, and 120 for those who remember back to cassette tapes). This is best exemplified by Tressie McMillan Cottom’s outstanding book playlist for her new essay collection Thick (now available for preorder). Here, too, the selection is terrific — and if I can say, a touch more personal and intelligible than Questlove’s epic collection.

If I ever write a book (and that day seems farther away every year), I’m definitely doing this. Hmm — I wonder what a Kottke.org playlist would look like? [smiles mischievously]

Update: Brett Porter points out that Thomas Pynchon created a playlist for Inherent Vice that includes songs mentioned in the book. Kyle Johnson notes that largehearted boy’s Book Notes series consists of book playlists by various authors each week inspired by their books, including “Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.”

(A version of this story is an excerpt from this week’s Noticing newsletter. You can read more about Noticing here.)

In a rare interview, Italian author Elena Ferrante observes that between corruption, poverty, violence, fear, and the deterioration of democracy, “today it seems to me that the whole world is Naples and that Naples has the merit of having always presented itself without a mask.” The world of Ferrante’s novels is the world in which we’ve all been living; the rest of us are just catching up to what Neapolitans have known all along.

It seems you could make a similar case for The Onion in the time of Trump: the world was already absurd and buffoonish, and now it’s taken off its mask. It does make telling jokes a touch more tricky. Editor-in-chief Chad Nackers explains the site’s approach, admitting that the writers’ job would probably be easier if Hillary Clinton had been elected.

What strikes me is how much he attributes to the site’s changes over the years isn’t to the administration, but to the atmosphere, which has changed since the days of Bill Clinton (and not just because of who’s been elected since).

When I started, there weren’t really too many humor sites. There definitely weren’t any humor news sites. A lot of times, nobody else was going to get their comment out as fast as we were going to get it out, by virtue of us having a website. Now it almost seems like on Twitter there are people who are professional comedians who are online all day. A story breaks and they’re making jokes about it.

Andy Baio recently posted a link that shows you your Twitter timeline as it would have looked ten years ago if you followed all the same people that you do today. For me, at least, it’s amazing how different the tone is — even in the middle of an historic election, in the early stages of an enormous economic meltdown, there’s a lot less politics, a lot less sniping, and a lot more diaristic writing. It’s not necessarily better; it’s just very different. And all of those things were happening then — it’s just that Twitter wasn’t understood as the venue where every stance was to be articulated, every statement was to be critiqued, and every line was to be drawn. There were fewer people around, it was a lot more homogenous, and far fewer people were paying attention.

I wonder often how future historians will think about this time (you know, with the usual grisly caveat that people survive to do history in the future): how much of today’s ugliness, violence, and corruption they will think of as an aberration of one man, or one family, one political party, one social media network, one television network, etc.

Or will they see it as an interlocking, self-contradictory system, all of which had a history, and all of whose parts shaped and enabled what happened — hopefully, good and bad things. I mean, even the people who’ve argued that the coup has already happened can’t agree on whether it began with the election, with Congress, or some time long before.

Maybe the future historians will be better at disentangling these things than we are. Or maybe we’re just all hopelessly tangled.

Reuters editor-in-chief Steve Adler wrote a message to staff called “Covering Trump the Reuters Way.” After noting that “Reuters is a global news organization that reports independently and fairly in more than 100 countries, including many in which the media is unwelcome and frequently under attack,” he lays down some do’s and do-not-do’s1:

Do’s:

—Cover what matters in people’s lives and provide them the facts they need to make better decisions.

—Become ever-more resourceful: If one door to information closes, open another one.

—Give up on hand-outs and worry less about official access. They were never all that valuable anyway. Our coverage of Iran has been outstanding, and we have virtually no official access. What we have are sources.

—Get out into the country and learn more about how people live, what they think, what helps and hurts them, and how the government and its actions appear to them, not to us.

—Keep the Thomson Reuters Trust Principles close at hand, remembering that “the integrity, independence and freedom from bias of Reuters shall at all times be fully preserved.”

Don’ts:

—Never be intimidated, but:

—Don’t pick unnecessary fights or make the story about us. We may care about the inside baseball but the public generally doesn’t and might not be on our side even if it did.

—Don’t vent publicly about what might be understandable day-to-day frustration. In countless other countries, we keep our own counsel so we can do our reporting without being suspected of personal animus. We need to do that in the U.S., too.

—Don’t take too dark a view of the reporting environment: It’s an opportunity for us to practice the skills we’ve learned in much tougher places around the world and to lead by example - and therefore to provide the freshest, most useful, and most illuminating information and insight of any news organization anywhere.

These are good rules. (That one about giving up on access and hand-outs is downright fire.) They’re particularly good rules for a place like Reuters, that has a specific style, tradition, and role in the news ecosystem.

But they’re not necessarily good rules for everybody. Different news organizations are going to need to fill different roles in the ecosystem, different spaces on the multiple axes of personal, political, intellectual, and business commitments. If Gawker were still here in its full glory, Nick Denton could write up “Covering Trump the Gawker Way” and it would probably be a totally different but equally valuable list of guidelines.

The other thing news organizations (and other companies too) will need to figure out in L’Age D’Trump are their commitments to their staff. Reporters and media organizations need legal protections so they can’t be prosecuted as criminals or sued by proxy billionaires for doing their job; but they also need to be able to talk freely about how to do their job and balance all of those commitments for themselves without being shown the door.

The pressure is going to be coming from a lot of directions, not always the obvious ones. When the stakes are this high, and the conditions this uncertain, it helps to allay as many uncertainties as possible. When the shit goes down, you need to know who’s going to have your back.

It’s the 70th anniversary of Orson Welles’s masterpiece Citizen Kane:

Audacity and genius his trademark, and with a third medium to conquer and transform, Welles didn’t think small. With the Mercury players in tow, he enlisted veteran satirist and screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz. Together they crafted a story that began with the death of an enigmatic protagonist, and explored his life through flashbacks told from multiple points of view. As questions are answered, questions are raised. The script ultimately compares a man’s life to a jigsaw puzzle missing pieces, and thus impossible to solve. The writers very loosely based the title character of Charles Foster Kane on William Randolph Hearst, thus incurring the newspaper titan’s wrath. Welles, Mercury, RKO, and the studio heads endured journalistic scandalmongering, and the film eventually earned a blacklist. Welles would later remark, “If Hearst isn’t rightfully careful, I’m going to make a film that’s really based on his life.”

By coincidence, as related by Welles in his autobiography, he once found himself alone in an elevator with Hearst. It was the night of Citizen Kane’s San Francisco premiere, and Welles invited him to the opening. “He didn’t answer. And as he was getting off at his floor, I said, ‘Charles Foster Kane would have accepted.’”

Everybody talks about the movie’s formal innovations, but I wish the content would get more love. As A.O. Scott says, “Citizen Kane shows Welles to be a master of genre. It’s a newspaper comedy, a domestic melodrama, a gothic romance, and a historical epic.” Pauline Kael said Kane was “more fun than any great movie I can think of.”

Citizen Kane is The Beatles of movies, not just because of its universal influence and acclaim, or because it really does live up to the historical hype, but because on top of its arty aspirations, what it really wants to do is entertain the hell out of you.

Also, if you’re watching it carefully, the movie’s self-reflexiveness hides and reveals a devastating history of media. You’ve got CFK, accidental heir to a fortune based on “oil wells, gold mines, shipping, and real estate,” who trades it all for a communications empire: newspapers, radio stations, paper mills, opera houses, and grocery stores, only to be pushed to the margins after a failed political run in favor of the next generation: magazines and movies, the trade of the newsreel producers who try to track down the labyrinthine origin of “Rosebud.”

The whole movie’s about trying to invent something from nothing, about pretenses to real value, and how that whole house of cards tumbles apart. Eventually you’ve just got a giant room, where you can’t tell the art from the jigsaw puzzles, the childhood heirlooms from the tchotchke snowglobes. Everything propping up value disintegrates. (That’s what Kane figures out at the end, by the way, not that he misses his sled or his mom.)

As Borges wrote, it’s a metaphysical detective story that leads us to a labyrinth with no center. All that’s left is paper, just kindling for the fire.

Two major media companies issued statements about workplace values in the last 24 hours or so. From New York Times owner Arthur Sulzberger’s in-house “diversity and inclusion” reminder email this morning: “Our Company is committed to diversity and inclusion, and our goal is to provide a stimulating, supportive environment where employees can thrive and grow, sharing their many experiences, attitudes, cultures and viewpoints.” Okay, fine!

But here’s from new Tribune Company owner Sam Zell: “Discrimination based on gender, age, race, religion, national origin, marital status, sexual orientation, disability, or any other characteristic not related to performance, ability or attitude, protected by federal or state law, or not protected (such as inability to tell a joke, the occasional poor wardrobe choice or bad hair day), is strictly prohibited…. Working at Tribune means accepting that sometimes you might hear a word that you, personally, might not use. You might experience an attitude that you don’t share.” Wow. (PDF download, via LA Observed.)

And there’s also this in the new Tribune manual: “Under Rule #1, you may want to think twice before you enter into an intimate relationship with a co-worker. When you start, it might seem like a good idea. It’s when you stop, or the wrong people find out (and they will) that you could discover that perhaps it wasn’t.” That is THE BEST ADVICE EVER. Does Sam Zell live… in the real world? Also in the new Tribune Manual: “It’s good judgment not to put in writing what you don’t want printed on the front page of a newspaper. Or posted on a web site. Or heard on the news.” This thing reads like it came out of some wacky internet startup. (Disclosure: I’m taking money from both companies. Uh, for now!)

Stay Connected