In living memory

Today is the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The full title is important because the right words are important.

@Soledad_OBrien Everyone forgets that the “March on Washington” was the “March for Jobs and Freedom.”

— Tim Carmody (@tcarmody) August 23, 2013

It’s important because the Great March itself was a compromise, an evolution of the movement A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters had forged decades before. During the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, Randolph and other civil rights leaders worked to force the government to desegregate the army and provide more economic opportunities to black Americans. The March was a dream, but it was also a threat. Before 1963, each time the March was about to happen, the government made concessions and it would be called off.

Randolph was 74 when the March finally materialized, with him as its titular head. He was the only figure with the credibility to unify northern labor leaders and southern pastors: radical enough for the relative radicals — the radical radicals saw the March as a distracting sideshow or were directly asked not to participate — and institutional enough for the wary moderates.

Bayard Rustin was Randolph’s lieutenant and did the bulk of the work organizing the March. Rustin was gay, and had been a Communist. He couldn’t be the event’s public face.

Special trains leaving from Penn Station to bring marchers to DC. Officials say it’s the largest early-morning crowd since end of WW2.

— Today in 1963 (@todayin1963) August 28, 2013

Everything that happened at the March, from the arrival of more than 100,000 people straight through all the speeches, all the songs, all the signs painted, all of the 80,000 cheese sandwiches made, distributed, and eaten — each and every one of those moments — happened in one day. Television stations were able to carry the event live. It was a tremendous feat of planning and organization. No one but Bayard Rustin and his dedicated staff could have pulled it off.

John Lewis was 23 years old and the March’s youngest speaker. He is the only one of that day’s speakers who is still alive. Lewis had recently been made head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC (pronounced “snick”). SNCC was a relatively new, independent civil rights organization that had proven itself integrating lunch counters in Nashville, then on the Freedom Rides with CORE protesting segregated busing and bus stations throughout the south, and working with the NAACP and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Albany, Georgia.

If you’re serious about the civil rights movement, you have to learn a lot of organizations’ names and abbreviated titles. You have to learn that the leaders of these organizations rarely agreed with each other about goals, methods, or priorities. You have to know that even within each organization there were equal amounts of discipline and dissent.

They were organized not because they agreed, but because they had to be. They were disciplined because they had to be. They were allied because they had to be. It was all fragile. At any moment, it could all fall apart.

John Lewis had been part of both series of Freedom Rides and was badly beaten during the second, in Montgomery. The state highway patrol that had promised the riders protection — at the insistence of the Kennedy administration and with the reluctant assurance of Alabama’s governor, George Wallace — abandoned them to a white mob waiting at the city’s station house.

Lewis was 21 years old. His friend Jim Zwerg was also 21. Zwerg bravely walked out the door of the bus first to meet the waiting mob, where he was nearly beaten to death. He received a particularly savage beating partly because he was first and partly because he was white.

While being beaten, Zwerg recalls seeing a black man in coveralls, probably just off of work, who happened to be walking by. “‘Stop beating that kid,” the man said. “If you want to beat someone, beat me.”

“And they did,” Zwerg remembered. “He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don’t know if he lived or died.”

Jim Zwerg is still alive. It’s amazing any of these people are still alive.

August 28, 1955, Emmett Till is murdered.

— Melissa Harris-Perry (@MHarrisPerry) August 28, 2013

Lewis was originally going to give a much more provocative speech at the March. The plan was to call out the supposedly liberal Kennedy administration for its lukewarm support of civil rights. (A less polite word than “lukewarm” would be “half-assed.”) On behalf of SNCC, Lewis would argue that the civil rights legislation proposed by the Kennedy administration was (in Lewis’s words) “too little and too late.”

But each of the March’s major figures, including Rustin and Dr. King, urged Lewis to moderate his speech. They had a testy but evolving relationship with the Kennedys that they didn’t want to jeopardize or aggravate. It was only A. Philip Randolph who finally swayed Lewis. Rustin went into the crowd to find Randolph, then brought the two men together.

Lewis was 51 years younger than Randolph. Lewis later said of Randolph that “if he had been born in another period, maybe of another color, he probably would have been President.” Randolph had been an actor as a young man, and his voice has that deep, archaic, clear-toned, echoing-from-infinity quality that you imagine is the voice of history itself; the voice you imagine reading the Gettysburg Address and Declaration of Independence.

Lewis and the other young leaders of SNCC were quite rightly in awe of him.

He was 75, and here we were, you know, one-third his age and, you know, he was asking us to do this for him. He said, “I waited all my life for this opportunity, please don’t ruin it.” And we felt that for him, we had to make some concession. [Courtland Cox]

The day’s speeches were already underway. This all happened in one day. Lewis was sixth on the program. So Cox and Lewis and James Forman went to the Lincoln Memorial — no bullshit, they went and sat together at the foot of the Lincoln fucking Memorial — and rewrote Lewis’s speech. It’s still pretty fierce.

To those who have said, “Be patient and wait,” we must say that “patience” is a dirty and nasty word. We cannot be patient, we do not want to be free gradually. We want our freedom, and we want it now. We cannot depend on any political party, for both the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of Independence…

The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it into the courts. Listen, Mr. Kennedy. Listen, Mr. Congressman. Listen, fellow citizens. The black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won’t be a “cooling-off” period…

We must say, “Wake up, America. Wake up! For we cannot stop, and we will not be patient.”

I was amazed recently to discover that Reverend Doctor Joseph E. Lowery, one of the co-founders of SCLC, is still alive at 91. He has three videos of interviews up at “His Dream, Our Stories,” a site devoted to the March. Lowery was a pastor in Mobile and helped lead the bus boycott in Montgomery — which, people forget, went on for over a year after Rosa Parks’ arrest. Later, Lowery, along with John Lewis, Hosea Williams, Martin Luther King Jr., and others, led the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. Ten years after Emmett Till’s murder and the Montgomery bus boycott, two years after the March on Washington, and a year after the Civil Rights Act, the Selma marchers were attacked by Alabama state and local police for asserting their right to vote.

In 2008, Lowery gave the benediction for Barack Obama’s first Inauguration. He is still alive. He is 91 years old.

The March all happened in one day; the Movement happened over years and years and years.

Rosa Parks was 42 when the Montgomery bus boycott began. She was 50 at the time of the March, where she was honored along with other important women of the Civil Rights Movement — Little Rock’s Daisy Bates, SNCC’s Diane Nash Bevel, Gloria Richardson of Cambridge, Maryland, and Mrs. Herbert Lee. The women’s many accomplishments and contributions were noted in a speech by Myrlie Evers-Williams, then listed as Mrs. Medgar Evers.

Parks was older than Lowery, who was 34 when the boycott began. Martin Luther King Jr. was 26, not much older than Lewis was when he was called to lead SNCC and speak in Washington. At the March, King was 34. Within five years, he would be dead. A. Philip Randolph would live to be 90 years old, just a little younger than Lowery is now. He outlived King by more than ten years.

We’ve lost so much. We’ve forgotten so much. We’ve asked so few to stand in for so many. We’re doing it still.

Copyright lawyer Josh Schiller recently wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post, “Why you won’t see or hear the ‘I have a dream’ speech,” examining how the King estate’s vigorous defense of his speech’s copyright has prevented its popular reproduction.

One place you can both see and hear King’s speech is on PBS’s Eyes on the Prize website. Eyes on the Prize is a landmark documentary on the entire modern civil rights movement, from Emmett Till’s murder through the 1980s, when it first appeared. Its producers know more than a thing or two about the thorniest issues of copyright: the documentary’s rebroadcast and distribution were held up for years while rights were cleared for its music, photographs, and videos. (Eventually, some of the original media was replaced.) I’m pretty sure they’ve done their work and paid the right licensing fees to get King’s speech on the website.

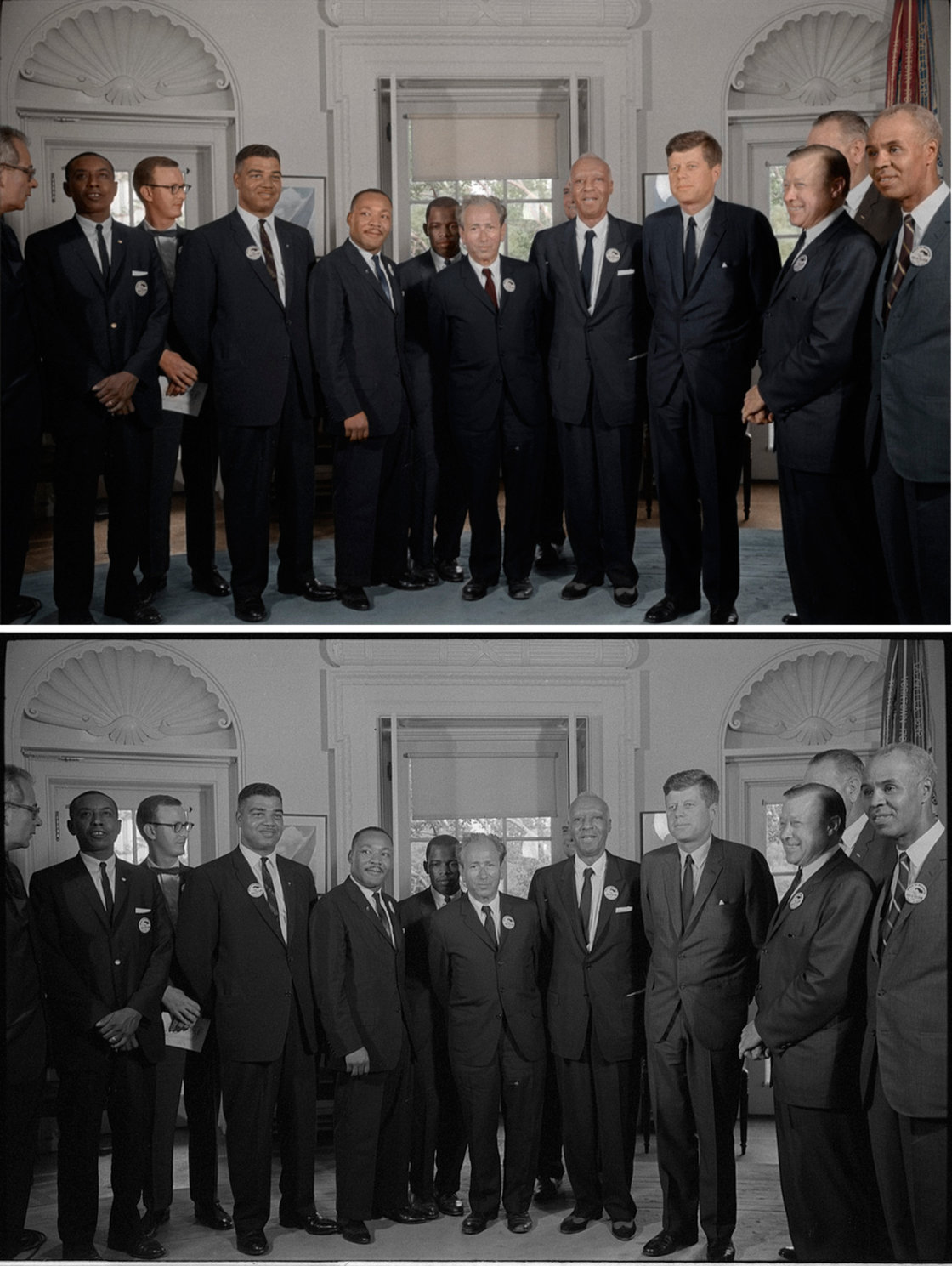

Watch Dr King’s speech. It’s not the entire thing, and it’s a crummy little QuickTime video. But it includes footage of the marchers arriving, A. Philip Randolph’s introduction, and footage of President Kennedy meeting with the March’s leaders, plus Walter Cronkite’s contemporary commentary.

Remember this is history, which means we are still within it, even when those for whom it has been living memory leave us. Remember that it is the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Remember how fragile it all was. Remember A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, Joseph E. Lowery and Jim Zwerg. Remember the man in coveralls, remembered by no one but the stranger whose life he saved.

Remember Martin Luther King, Jr., that thickly-built, still-young man, rooting his feet in our history and turning himself into a column of pure energy, like a beacon through time and space, a light so bright we can’t look at him directly, but have to turn away and look only at his half-remembered shape, still impressed on us when we close our eyes. Remember that day, when he all-too-briefly became a single still point with the granted power to bend straight the crooked lines of history.

Remember that fifty years after the Emancipation Proclamation, A. Philip Randolph was organizing the Shakespearean Society in Harlem. Fifty years after that, he was meeting a President who now owed him more than he probably ever knew. Fifty years is a long time and yet not so very long. If so much can be done in just one day, how much more could we do, now that we know we have another fifty years?

Image colorized by Mads Madsen for NPR.

Image colorized by Mads Madsen for NPR.

Stay Connected