Active, passive, or playing?

I’ve always thought that passivity is underrated. One of the nice things about going to the movies is that once you’re there, everything just happens to you. In the seventies, film theory took on a lot of anti-consumerist and weirdly sexual politics where, for some reason, it was better to be active than passive, which always just feels very vanilla. I mean, sometimes you’re active, sometimes you’re passive, and sometimes you’re just playing around, which isn’t really either, but all three are good.

You could apply this three-part scheme to a lot of things (three-part schemes are good for that), but I thought of it reading this 1997 essay “The Book and the Labyrinth,” on cybertexts and literature that, like a lot of games we’re familiar with, cycles through a variety of different architectural possibilities.

The author, Espen J. Aarseth, gives three predigital historical examples of this kind of literature: the I Ching, which is literally random, like throwing dice; Apollinaire’s Caligrammes, which contains more like concrete poetry that can be read in multiple (or sometimes just unexpected) directions (there are plenty of “traditional” free verse poems in that book, too); and Raymond Queneau’s Cent Mille Milliards de Poemes (One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems) — which sounds about as right in French as “a million billion trillion dollars” does in English — ten sonnets printed on cards with each line on a separated strip, where all the lines can be recombined to produce new sonnets in any sequence.

Whitney Anne Trettien calls these “text-generating mechanisms,” and her thesis (Computers, Cut-ups & Combinatory Volvelles) offers much more history on this kind of literary play, while also being an excellent example of what Aarseth would call a cybertext.

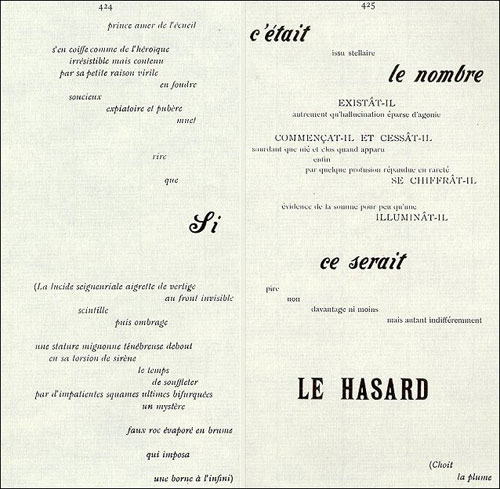

My two favorites, however, are both by French poet Stephane Mallarme. (The French love these things almost as much as they love their accented vowels.) This is an image from his poem “Un coup de des jamais n’abolira le hasard” or “A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”:

You can read the poem linearly (such as it is), but even to find its putative title, you have to skip words, finding a thread in different fonts and sizes. It’s the first (and maybe the last) truly avant-garde poem that uses space this way. And it never turned out exactly the way Mallarme wanted it.

He had precise instructions on the layout of the poem, he had precise instructions on the layout of negative space, he had precise instructions on the kind and quality of paper to be used, the type of binding, and so forth. This radical, go-in-any-direction-you-wish experiment was through-designed in a way that was impossible to fulfill.

It’s not a poem even as we would recognize it. It’s an architecture.

My other favorite example was called simply Le Livre (The Book), or sometimes The Great Work. We don’t even know its contents. All we have are unpublished notes that detail (in part) its physical arrangement and rearrangement, storage, where the reader of the book would stand in relationship to the audience while a reading was performed (yes, this book would be performed), how much money would be charged, how many performances could occur in each day, etc., etc., etc.

It’s like having detailed instructions for the proper handling of the ark of the covenant, and no ark. And it wasn’t lost — there never was one.

And that may be where we are. The only way to abolish chance — to create the space for action, audience, and game simultaneously — may be to create a structure with nothing inside, no mistakes to be made because there is nothing for them on which to be made, “a labyrinth with no center” (which is what Borges called the “metaphysical detective story” Citizen Kane).

Mallarme invented vaporware, the LOST questions that never get answered, the giant 404. It wasn’t his fault. It was supposed to be great.

Stay Connected