Old people, like those who live to be older than 30, didn’t exist in great numbers until about 30,000 years ago. Why is that? Anthropologist Rachel Caspari speculates that around that time, enough people were living long enough to function as a shared cultural hard drive for humans, a living memory bank for skills, histories, family trees, etc. that helped human groups survive longer.

Caspari says it wasn’t a biological change that allowed people to start living reliably to their 30s and beyond. (When she looked at other populations of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens that lived in the same place and time, the two different species had similar proportions of old people, suggesting the change was not genetic.) Instead, it was culture. Something about how people were living made it possible to survive into old age, maybe the way they found or stored food or built shelters, who knows. That’s all lost-pretty much all we have of them is teeth-but once humans found a way to keep old people around, everything changed.

Old people are repositories of information, Caspari says. They know about the natural world, how to handle rare disasters, how to perform complicated skills, who is related to whom, where the food and caves and enemies are. They maintain and build intricate social networks. A lot of skills that allowed humans to take over the world take a lot of time and training to master, and they wouldn’t have been perfected or passed along without old people. “They can be great teachers,” Caspari says, “and they allow for more complex societies.” Old people made humans human.

What’s so special about age 30? That’s when you’re old enough to be a grandparent. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers and historical records suggest that when older people help take care of their grandchildren, the grandchildren are more likely to survive. The evolutionary advantages of living long enough to help raise our children’s children may be what made it biologically plausible for us to live to once unthinkably old ages today.

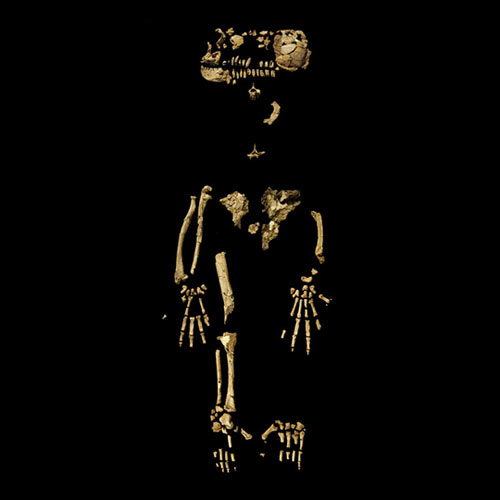

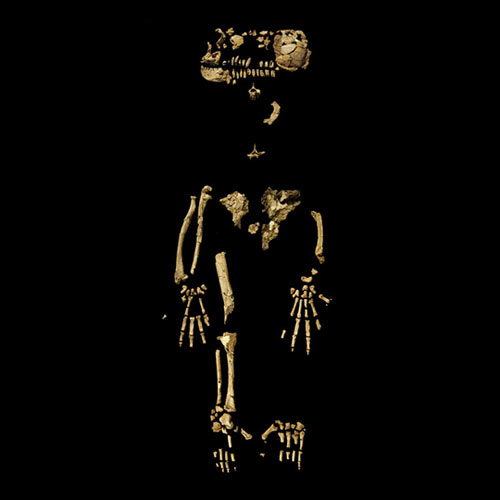

Internet, meet Ardi, the newest member of the human branch of the primate family tree.

Or rather, the oldest. Discovered in Ethiopia in 1994, Ardi is a 4.4 million-year-old partial skeleton of a female Ardipithecus ramidus.

The fossil puts to rest the notion, popular since Darwin’s time, that a chimpanzee-like missing link — resembling something between humans and today’s apes — would eventually be found at the root of the human family tree. Indeed, the new evidence suggests that the study of chimpanzee anatomy and behavior — long used to infer the nature of the earliest human ancestors — is largely irrelevant to understanding our beginnings.

Ardi instead shows an unexpected mix of advanced characteristics and of primitive traits seen in much older apes that were unlike chimps or gorillas. As such, the skeleton offers a window on what the last common ancestor of humans and living apes might have been like.

This is a major discovery; Science is devoting a special issue to the find with 11 detailed peer-review papers and general summaries. I expect we’ll be hearing more about this in the coming weeks as all that science filters through the lay media. (thx, jeff)

Is the recently revealed 47 million-year-old primate fossil a missing link or an overhyped publicity stunt?

But despite a television teaser campaign with the slogan “This changes everything” and comparisons to the moon landing and the Kennedy assassination, the significance of this discovery may not be known for years. An article to be published on Tuesday in PLoS ONE, a scientific journal, will report more prosaically that the scientists involved said the fossil could be a “stem group” that was a precursor to higher primates, with the caveat, “but we are not advocating this.”

From the scientific paper’s conclusion/significance section:

Darwinius masillae represents the most complete fossil primate ever found, including both skeleton, soft body outline and contents of the digestive tract. Study of all these features allows a fairly complete reconstruction of life history, locomotion, and diet. Any future study of Eocene-Oligocene primates should benefit from information preserved in the Darwinius holotype. Of particular importance to phylogenetic studies, the absence of a toilet claw and a toothcomb demonstrates that Darwinius masillae is not simply a fossil lemur, but part of a larger group of primates, Adapoidea, representative of the early haplorhine diversification.

Some recent research on the wrist bones of the so-called hobbit skeleton suggests that Flores man is an ancestor of modern humans and not just diseased homo sapiens. The debate continues. (via npr)

A letter from the Paleoanthropology Division of the Smithsonian Institute: “We have given this specimen a careful and detailed examination, and regret to inform you that we disagree with your theory that it represents ‘conclusive proof of the presence of Early Man in Charleston County two million years ago.’ Rather, it appears that what you have found is the head of a Barbie doll, of the variety one of our staff, who has small children, believes to be the ‘Malibu Barbie.’”

Update: Not that there was any doubt that this isn’t a real letter, here’s the confirmation. (thx, sam & sheldon)

A US antropologist says that weaker toes found in human skeletons from 26,000-40,000 years ago indicates when humans started wearing sturdy shoes.

Stay Connected