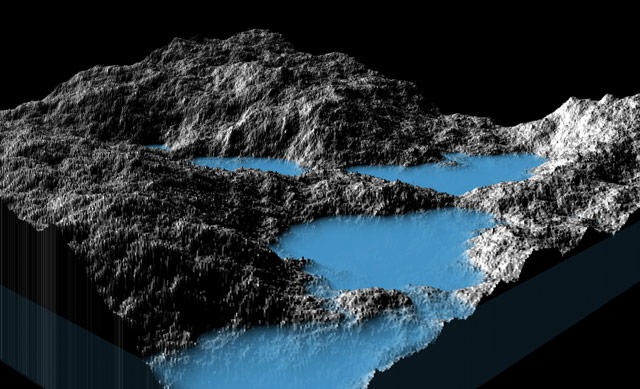

Hunter Loftis has built a terrain rendering engine in only 130 lines of Javascript. Here’s what the output looks like:

Programmers tend to be lazy (I speak from experience), and one nice side effect of laziness is really brilliant ways to avoid work. In this case, instead of spending mind-numbing hours manually creating what would likely be pretty lame rocky surfaces, we’ll get spiritual and teach the computer what it means to be a rock. We’ll do this by generating fractals, or shapes that repeat patterns in smaller and smaller variations.

I don’t have any way to prove that terrain is a fractal but this method looks really damn good, so maybe you’ll take it on faith.

You can try it out here…reload to get new landscapes. Callum Prentice built an interactive version. This obviously reminds me of Vol Libre, a short film by Loren Carpenter from 1980 that showcased using fractals to generate terrain for the first time.

In 1980, Boeing employee Loren Carpenter presented a film called Vol Libre at the SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference. It was the world’s first film using fractals to generate the graphics. Even now it’s impressive to watch:

That must have been absolutely mindblowing in 1980. The audience went nuts and Carpenter, the Boeing engineer from out of nowhere, was offered a job at Lucasfilm on the spot. He accepted immediately. This account comes from Droidmaker, a fascinating-looking book about George Lucas, Lucasfilm, and Pixar:

Fournier gave his talk on fractal math, and Loren gave his talk on all the different algorithms there were for generating fractals, and how some were better than others for making lightning bolts or boundaries. “All pretty technical stuff,” recalled Carpenter. “Then I showed the film.”

He stood before the thousand engineers crammed into the conference hall, all of whom had seen the image on the cover of the conference proceedings, many of whom had a hunch something cool was going to happen. He introduced his little film that would demonstrate that these algorithms were real. The hall darkened. And the Beatles began.

Vol Libre soared over rocky mountains with snowy peaks, banking and diving like a glider. It was utterly realistic, certainly more so than anything ever before created by a computer. After a minute there was a small interlude demonstrating some surrealistic floating objects, spheres with lightning bolts electrifying their insides. And then it ended with a climatic zooming flight through the landscape, finally coming to rest on a tiny teapot, Martin Newell’s infamous creation, sitting on the mountainside.

The audience erupted. The entire hall was on their feet and hollering. They wanted to see it again. “There had never been anything like it,” recalled Ed Catmull. Loren was beaming.

“There was strategy in this,” said Loren, “because I knew that Ed and Alvy were going to be in the front row of the room when I was giving this talk.” Everyone at Siggraph knew about Ed and Alvy and the aggregation at Lucasfilm. They were already rock stars. Ed and Alvy walked up to Loren Carpenter after the film and asked if he could start in October.

Carpenter’s fractal technique was used by the computer graphics department at ILM (a subsidiary of Lucasfilm) for their first feature film sequence and the first film sequence to be completely computer generated: the Genesis effect in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. The sequence was intended to act as a commerical of sorts for the computer graphics group, aimed at an audience outside the company and for George Lucas himself. Lucas, it seems, wasn’t up to speed on what the ILM CG people were capable of. Again, from Droidmaker:

It was important to Alvy that the effects support the story, and not eclipse it. “No gratuitous 3-D graphics,” he told the team in their first production meeting. “This is our chance to tell George Lucas what it is we do.”

The commercial worked on Lucas but a few years later, the computer graphics group at ILM was sold by Lucas to Steve Jobs for $5 million and became Pixar. Loren Carpenter is still at Pixar today; he’s the company’s Chief Scientist. (via binary bonsai)

Stay Connected