‘The Last Time a Vaccine Saved America’

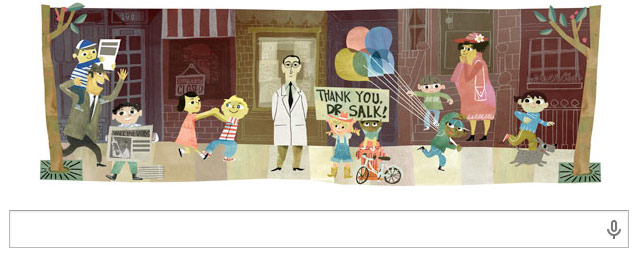

In 1955, epidemiologist Thomas Francis Jr. announced the results of a field trial of the polio vaccine that Jonas Salk had developed. America erupted in joy.

Now a phalanx of bulky television cameras focussed on Francis as he prepared to report on the efficacy of the vaccine. He had good news to share: to cheers from the audience, he explained that the Salk vaccine was sixty to seventy per cent effective against the most prevalent strain of poliovirus, and ninety per cent effective against the other, less common strains. All this had been shown through what was, at that time, the largest vaccine trial ever conducted.

All afternoon and evening, church bells rang out across America. People flooded into the streets, kissing and embracing; parents hugged their kids with joy and relief. Salk became an instant national hero, turning down the offer of a ticker-tape parade in New York City; President Dwight D. Eisenhower invited him to the White House and, later, asked Congress to award him a Congressional Gold Medal. That night, from the kitchen of a colleague’s house, Salk — whose name was being touted in newspapers, magazines, radio reports, and television news broadcasts around the world — gave his first network-TV interview to Edward R. Murrow, whose show “See It Now” had exposed the tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy a year earlier. Blushing in admiration, Murrow asked the doctor, “Who owns the patent on this vaccine?” “The people,” Salk said, nobly. “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

In the days that followed, schoolchildren were instructed by their teachers to write thank-you notes to Salk. Universities lined up to offer him honorary degrees. Millions of American doctors, nurses, and parents got down to the serious business of vaccinating their children against polio, using a shot they’d been anticipating for seventeen years.

But the polio vaccine rollout had its challenges, including a manufacturing negligence & oversight failure that resulted in tens of thousands of polio cases in otherwise healthy children.

In May, the polio vaccination drive was temporarily suspended. Leonard Scheele, the U.S. Surgeon General, inspected the facilities of all six vaccine companies and fired the government officials he considered to be culpable; the director of the N.I.H. and the Secretary of Health voluntarily resigned. New safety procedures were developed, including an improved means of filtering the viral mix just before the formaldehyde was added. Better tests were developed to detect live virus, and stricter record-keeping was instituted. The incident could have created a vaccine-hesitancy crisis. But, incredibly, the American public readily accepted the medical establishment’s explanation for the failure, and its pledges to right the situation. The nation’s trust in medical progress and in Dr. Salk was so resolute that, when it was announced that a new, safe polio vaccine was available, parents pushed their children back to the head of the line. It’s hard to imagine such an outcome today.

Socials & More