Writing for the smell of it

Earlier this week, I wrote about how literature transforms text into voice and experience — the word made flesh, basically. But the examples I used of “experience” focused, as such discussions often do, on the image: in other words, vision. And it should be obvious that embodied experience is much richer than that. Experience is tactile and spatial, mental and auditory. It’s not photography; it has a taste and a temperature.

Smell might be the most ineffable feature of animal life. Words and food go through the mouth, so language and taste have a more intimate relationship than it does with smell, the seat of breath. The language of taste colonizes other experiences almost as much as vision does. The word “taste” alone testifies to this.

Smell is more delicate, and harder to explain or describe. In conversation, we have words, sure, but mostly communicate smell through grunts or exaggerated faces. Or again, through analogy with taste — with which it’s closely linked.

It’s probably safe to say that the deeper we move into language, especially the more cerebral side of language, the more alienated we become from smell. The world stops being beings among beings, and becomes res extensa.

Still, writers have to try to find a way to square this circle. How do you do it? Do you try to dominate the reader and go all pulpy, immersive, and visceral? Or do you write around it: using smell as a starting point for memory and sensibility, counting on readers to fill in the gaps?

Consider this passage from Helena Fitzgerald and Rachel Syme’s perfume newsletter, The Dry Down:

What we know as “leather” in scent is really an intellectual idea and not a true distillation of anything; it’s the ingenious concept of covering up the smell of dried-out skins with flowers so that these skins can be sold as luxury goods. The real story behind this idea is one of violence and hideous smells: many of the bloody, gut-strewn tanneries of 16th century France were located in close proximity to the Grasse perfume distilleries (where flowers were also sent to their deaths by hot steam or being suffocated in tallow), so close that the air in town became a heady melange of life and death, all mixed up; it must have smelled overwhelming and nauseating and murderous and terrifying (but then, that was the way most of Europe smelled before sewage systems were invented). Legend has it that this intermingling began when Catherine de Medici came over from Italy to rule France in 1547 and asked the Grasse tanners to start scenting their gloves with jasmine to rid them of the putrid scent of the kill; oiled gant then became de rigeur among aristocratic French try-hards…

It was all the rage to pretend that the dead thing you were wearing on your hands arrived to your palace smelling like a rose; and that’s still pretty much where we are with leather. When you close your eyes and think of what a pure leather smells like to you (a S&M dungeon? Frye boots crunching over autumn leaves? A tawny satchel worn down by years of use?), what you must know is that whatever you are imagining is an artificial smell, a clever creation passed down from some genius in post-classical Provence who conjured up a way to give a pushy queen exactly what she desired. That smell of suede, of the inside of a new handbag, that’s always a damn lie. Actual leather smells like rotting, like wretching, like rigor mortis. It’s not pleasant, but then, luxury is about high-stakes deceit, about playing hide-the-damage inside buttery language and astronomical price tags.

Later, Rachel writes about a perfumer she met names Stephen Dirkes:

When we first met, Dirkes brought me real ambergris to smell, waving an antique tin of pungent whale belly under my nose; I will never forget it. He also brought civet and castoreum, true animal secretions, to show me how very close to death we are at all times when we love perfume. These materials don’t smell fresh or vibrant, they smell like the other side of the bell curve, the decline, the decay. Stephen was the first person to tell me about the Grasse tanneries, and I remember he said something like “There is a death drive in these smells,” and that perfume is often an expression of self-loathing as much as it is of self-love. And that’s what leather is to me. You can’t wear it unless deep down, you loathe humanity as much as you love it, unless you acknowledge the gory hidden history of our hedonism, unless you know, in your heart, that opulence is a cover-up job.

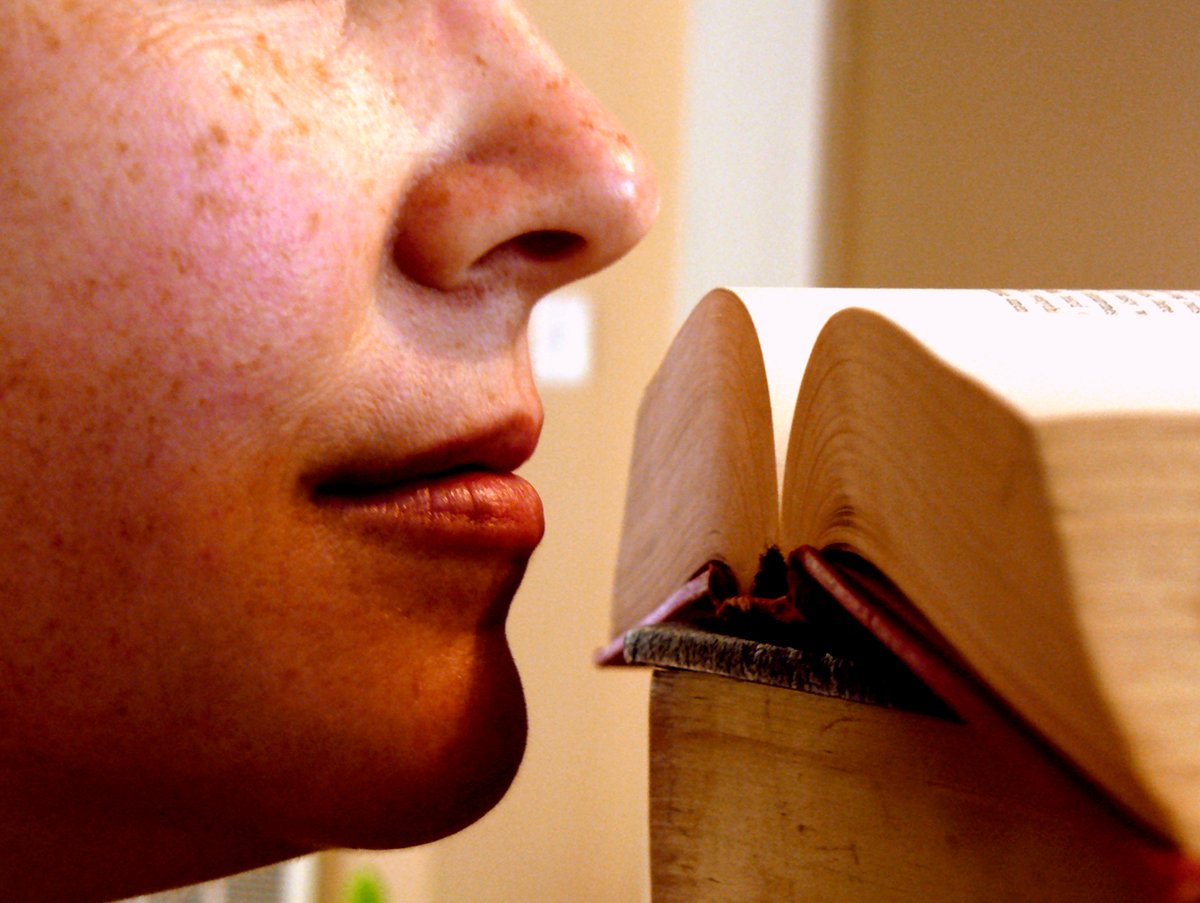

Helena, in the same newsletter, writes the following beautiful observation about the smell of books:

What makes old book smell work as a scent that can be worn on the skin is a leather note, and the other smells that mingle in a university library, the kind of place where more hidden corners, more secret hide-outs, reveal themselves the longer you stay - the undercurrent of cooped-up people’s sweat, a hum of anxiety and ambition and want, the waft of the snacks that somebody snuck in, the sudden out-of-place hope when someone cracks a window, the residue of cigarettes clinging to people’s hair and clothes when they come back in from one more smoke break during a marathon study session. It smells like the gummy, self-satisfied leather of old book bindings and the grateful sinking feeling when you flop onto a broken-down Chesterfield sofa. Leather dominates New Sibet, but it is rounded out by notes of ash and carnation, iris and fur and moss, and it comes together to smell like a library not in the romantic Beauty and the Beast sense of a library, but the lived-in, slightly gross, sleep-deprived, buzzing all-too-human and really pretty rank smell of a college library. Old book smell made human is admittedly a little bit gross, in the way that even the fanciest college with the most prestigious pedigree, the most beautiful wrought iron gates and most gracious green quadrangles is still full of college students, and college students are inevitably kind of disgusting. But that human grossness is what’s missing from old book smell, and it’s what makes New Sibet into a wearable expression of old book smell. It smells not just like books but like their context, the people crowding in around them, the bodies sinking time as lived experience into the leather covers of old books through their human smell.

I’m not much of a perfume person. I am, however, a writing and smelling person. And I love the way Helena and Rachel write about smells.

Via Amanda Mae Meyncke, who adds:

This is the thing I’ve told more people about in 2017 than anything else — it is an utter delight. I never cared about perfume at ALL before this, and their writing is so good and so precise, so intelligent and so ACCURATE, that every suggestion they’ve made has smelled exactly like their descriptions — which are a mixture of memory, sense, history and more — and they’ve done the impossible, making this aloof-seeming shit absolutely accessible and delightful.

(This is also a relatively cheap, luxurious, happy-making hobby in the midst of perilous times.)

Stay Connected