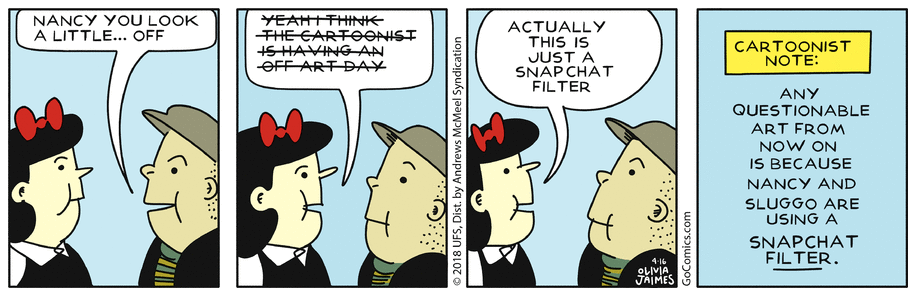

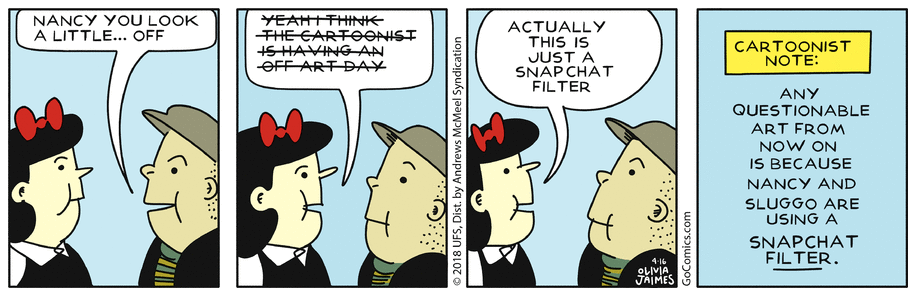

At Vulture, my father* Abraham Riesman scored an interview with Olivia Jaimes, a mysterious young (?) cartoonist who’s resurrected the venerable strip “Nancy” for the 21st century.

Do you remember how you first got exposed to “Nancy”?

I read newspaper strips, so she was kind of in the air I was breathing. And my parents actually have an original “Nancy” in the house that I’ve read now, maybe, 10 million times. I’ll describe it to you.

Please.

Okay, so, panel one, Nancy’s looking at Sluggo and she’s like, “I really wish that guy would take a bath.” And then in panel two, she’s thinking really hard about soap and her eyes are looking at him and there’s a dashed line. And then in the third panel he hasn’t taken a bath, but instead, he’s sitting on a soapbox, blowing soap bubbles, and listening to a soap opera. She has not succeeded in her goal. I was really more into Pokémon. When I was reading the newspaper strips, I was like, No, what I gotta read is “Zits” and “Mutts” and other things that are cool for me, age 9. It wasn’t until I was in my early 20s that I really got into “Nancy,” and it was because there was a Tumblr that just posted panels out of context. Like, Nancy imagining a bank blowing up, or Nancy parading around banging something really loud. They were a gateway to more Nancy for me.

On her vision for the comics:

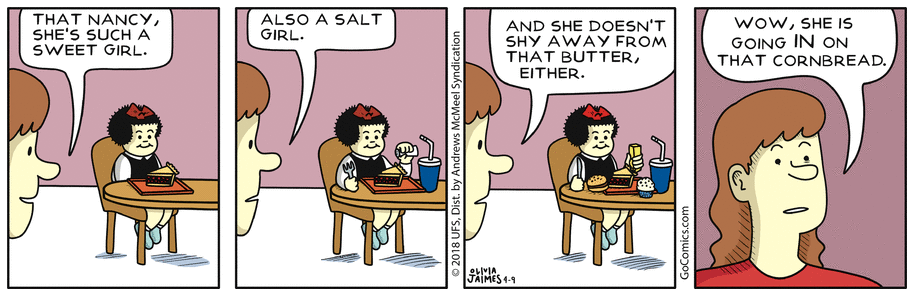

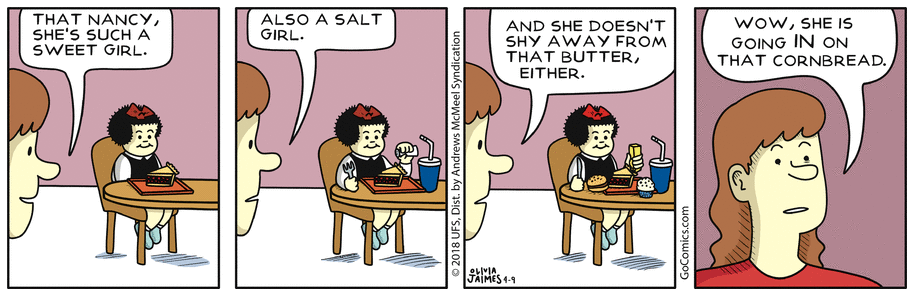

Why did you decide to lead off your run on the comic with the strip about Nancy eating corn bread?

I went back and I looked at the end of [previous “Nancy” cartoonist] Guy Gilchrist’s run. Nancy as a character had drifted from where I envision her, in that the Nancy I know and love is a total jerk and also gluttonous and also has big feelings and voraciously consumes her world. And I was like, I need to do a character-reset week. Just kinda being like, Here’s who Nancy’s gonna be right now. And also, I love corn bread. So, that’s it. That’s the reason. I wanted to reset expectations and pay homage to my favorite food.

It’s funny that you say the Nancy you know and love is a jerk because that plays into my thesis about why your version of the strip has caught on. We’re living in this era of a curious sort of hedonism, where we’re totally aware and ashamed that we’re being slothful and vain and greedy, but we continue doing it all anyway. Nancy is our avatar, and we look at her and laugh because we see how terrible we, ourselves, are. Or maybe I’m off base.

No, that’s so true! Okay, so, yeah, I wanna talk more about this with you because I think you’re really onto something. There’s this thing in webcomics: #relatable. And #relatable can be used as a slur. To be like, “Uh, your comic is pandering to people.” I’m almost always in the camp where … It’s not like comics are easy, but I think it’s great to be relatable, and I don’t want people to use relatable as an insult. I feel like Nancy is #relatable, except that she also isn’t apologetic. So, there’s the camp of #relatable, which is like, “I’m the worst person: I can’t stop eating bread,” or “I can’t get out of bed,” and like, Nancy is that, but then she’s also like, “So what?” The kind of self-hating type that often comes with relatable comics. The self-hating part that often comes with #relatable comics is being like, “Ohhhh, I procrastinated, I’m the worst.” And “Nancy” adds one more panel to that, being like, “Who cares? I don’t care. More corn bread for me.”

On why Nancy is studying robotics:

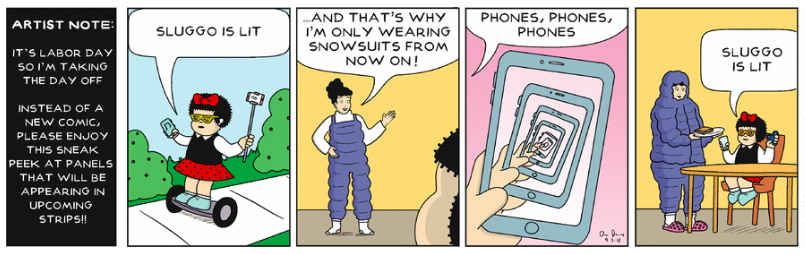

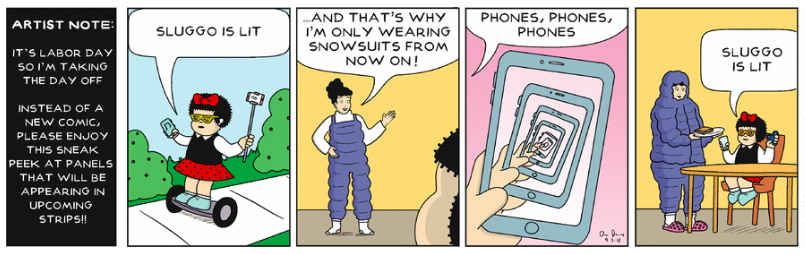

I realized that all of the nouns that Nancy used to have are being supplanted by a phone. Things that she would have lying around the house to make up a joke are gone. She uses megaphones for a ton of things in Bushmiller’s strips, and I don’t have megaphones lying around my house. So how, then, can Nancy solve problems, given that technology is advancing to the point where problems are being solved in really nonphysical ways? That’s why I’m making her learn robotics. It opens up a wider range of visual gags to make down the line.

It’s been a long, long time since I read a daily comic strip. Probably The Boondocks in its heyday, or one of the Bloom County resurrections. But I read Nancy. It’s consistently warm, weird, current, and good.

* Abe’s not actually my dad, it’s just a fun running gag between redheads

What’s nice (if exhausting) about Star Wars is that you can never run out of Star Wars content, because you can talk about Star Wars forever. Maybe you can do this about anything, and in an alternate universe, we’re talking about the Rocky franchise like it’s Talmud. But I think Star Wars both gives you enough material and leaves you enough conceptual empty space that it’s possible to just generate talk and talk and talk.

In an ongoing franchise, this runs the risk of that empty space collapsing and fans feeling like their imaginations have been foreclosed. Again, this happens to every fandom, but Star Wars fans seem to take it pretty hard.

Consider the Jedi. Even if you haven’t seen The Last Jedi yet, you know if you’ve seen The Force Awakens that characters in the new trilogy are using the Force to do things the Original Trilogy and prequels implied either required a lot of training or exceptional genetic gifts, and ideally both. In the new trilogy, the rules feel a little looser. Light sabers and force magic are things that some people are better at than others, sure, but they also can… kind of just do. And oh my, does this have people in their feelings.

Writing for The Week, Lili Loofbourow does a good job of explaining why:

The fact that Johnson’s Star Wars is more “democratic”… means, paradoxically, that it is also less interested in the rituals of samurai training that made Star Wars so satisfying. Becoming a great Jedi warrior used to be serious work; it demanded talent and skill and time. Later it seemed to require an aristocratic bloodline as well (what with the midi-chlorians, etc.). Now it just demands talent and no study… What was the point of Yoda? Do the sages have nothing to tell us? Did they ever?

See, there’s actually a three-part division here. The original trilogy emphasizes spiritual and physical training; the prequels, bloodline or origins; the new trilogy, being gifted and/or rising to the moment.

And actually, there are strands of all three theories in all three sets of movies. It’s just a question of relative weight. Training is important in the original trilogy; it’s also important in the prequels — they talk about it all the time! — and in the new movies (The Last Jedi is basically about Rey looking for a teacher from start to finish).

But training also became important to fans who rejected the introduction of midi-chlorians in the prequels. No, they said — the force isn’t about alien doodads in your bloodstream, it’s about training and discipline. It might be strong in families, but it’s available to anyone. So they leaned particularly hard on that crutch, only to see it (seemingly) kicked out of the way. And the fandom came crashing down.

One theory I really like comes from Abraham Riesman. It’s misleadingly titled “The Case for Midi-Chlorians.” What it really says, as I read it, is that the Jedi themselves do not fully understand what the Force is. Consequently, at different moments, and in response to different crises, they reinterpret it. They go into exile; they restore temples; they abandon them.1 They do not have it figured out, but are always refiguring it out for themselves, and for us.

Maybe midi-chlorians are as stupid an explanation of the Force as their real-world critics say they are. What if high midi-chlorian counts had a loose correlation to Force sensitivity, but weren’t actual causes of it, and the Jedi just misinterpreted their data? What if this was something like medieval doctors rambling on for centuries about humors and leeches — a faux-scientific delusion that was wholeheartedly embraced by a guild of people who loved to preach their own greatness to the hoi polloi? Perhaps the Jedi had thunk themselves into utter stupidity on an array of matters. Midi-chlorians were just one manifestation of their high-minded idiocy. From that point of view, the prequels are a tragedy about well-intentioned intellectuals whose myopic condescension led them onto a path of war and self-immolation…

So how do we explain the fact that Luke’s trainers don’t mention them?

I like to think it’s because they realized in their old age that midi-chlorians aren’t worth worrying about. Yoda and Obi-Wan had decades to ponder the nature of the Force and refine their conception of it down to its essence. Maybe, in looking back on the downfall of the Jedi, they realized that hewing too closely to specific explanations of the Force was a fool’s errand, a pseudo-intellectual distraction from what’s really important: spiritual contemplation and selfless deeds. As such, they may have thought Luke had the opportunity to build a future Jedi Order that wouldn’t repeat their mistakes. Like their decision to hide Leia’s familial relationship to him, they felt that Luke was better off without certain tidbits — and, unlike their dissembling about his sister, this was a worthwhile sin of omission. A condescending one, yes, but hey, old Jedi habits die hard.

Ultimately, both Riesman and Loofbourow come back to the same point: different people like Star Wars for different reasons, and we’re constantly jettisoning the bits we don’t like in favor of the ones we do. And the Jedi are doing that too.

This touches on my own personal fan theory, which is that the Jedi are better off and more interesting when they act less like samurai and more like ninja. Vader is 100 percent a samurai. He dresses like one, he acts like one: a loyal and noble retainer to state power. Obi-Wan in the original trilogy is not a samurai. He’s a trickster, a wizard, who uses misdirection and stealth rather than, well, force. He’ll throw down when he has to, but even his fight with Vader is more of a sleight-of-hand than an iron fist.

The Jedi should never have been the police force of the galaxy. They’re not Thors, but Lokis. They should have been rumors, legends. They don’t wear recognizable uniforms, but either simple robes or black cloaks. None but the initiated should have ever known they were real.

But maybe that is just the ethos of an order in exile, as the ninja were said to have been, scattered and displaced to the mountains of Japan.2

Maybe ninja is what you become when you can’t be samurai any more. When the old ways stop working, invent new old ways.

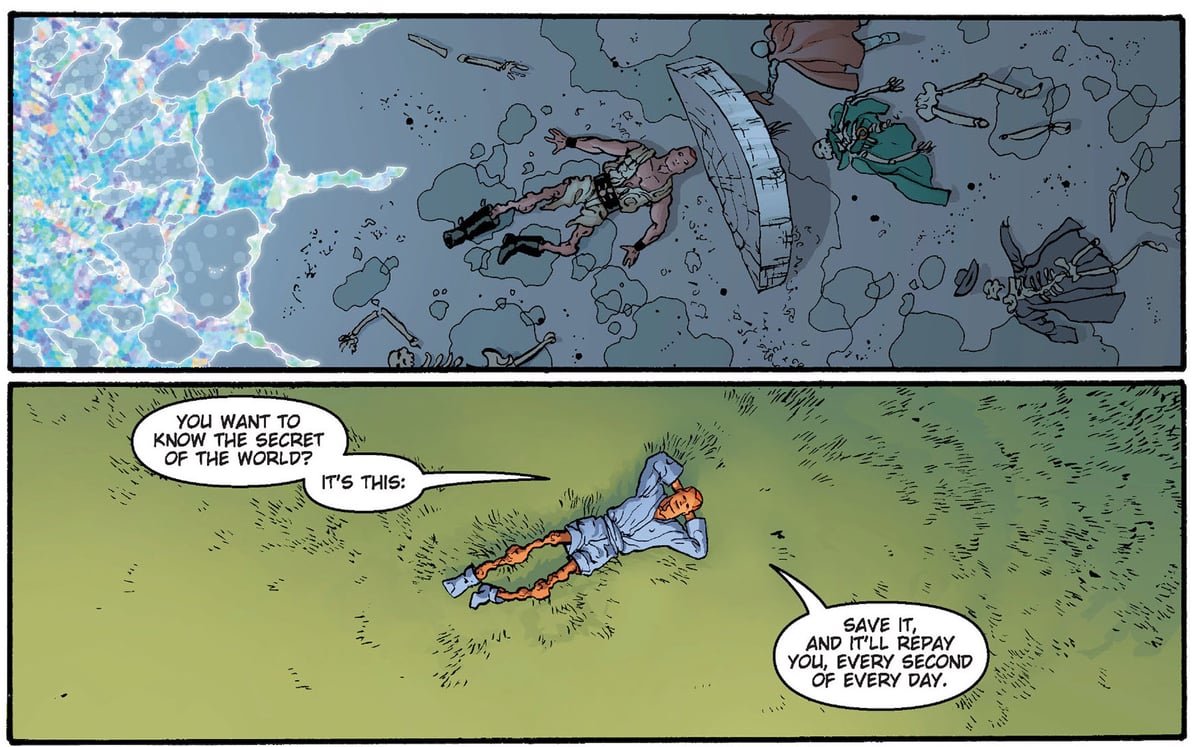

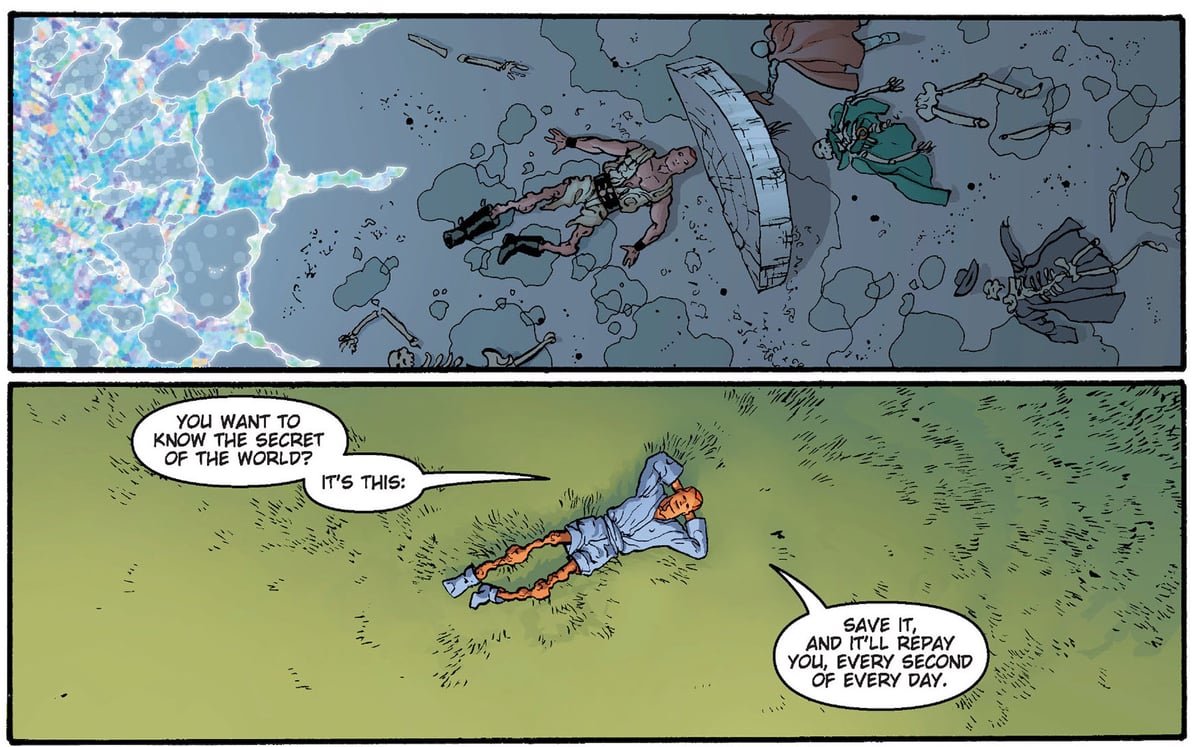

by John Cassaday and Laura Depuy, from Planetary 3: “Dead Gunfighters”

I called “American Captain” the best anti-superhero comic about superheroes. I need to qualify that. “American Captain” cares about superheroes, but not about superhero stories; Planetary, on the other hand, by Warren Ellis, John Cassady, and Laura Martin, cares about superhero stories, but not about superheroes.

Planetary’s main character, Elijah Snow, has a pretty classic superpower: he freezes things. Or rather, subtracts their heat. He’s a century-old detective, collector, and preservationist, and at the beginning of the story, he’s lost his memory. He joins a team of superpowered mystery archeologists, who beginning in 1999, aim to excavate the hidden wonders of the 20th century. Every one of its 27 issues explores a new mystery, in a new artistic style, while also propelling us to Elijah’s unlocked memories, the characters’ unraveled backstories, and an ultimate confrontation.

Unsurprisingly, I love this book.

The first thing it does is reinvent its own precursors. It reaches past the Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages of superheroes into the genre-rich world of the pulps. Snow turns out to be part of a cohort of century-old adventurers that include analogues of Tarzan, Fu Manchu, Doc Savage, and The Shadow. (Later we see versions of The Lone Ranger, Dracula, and Sherlock Holmes.) This group fights off an evil version of DC’s Justice League. Doppelgangers of DC and Marvel superheroes appear and reappear, but they’re either supervillains or easy victims of corporate and government power. Superheroes are not to be trusted. (One exception: an analogue of John Constantine who morphs into Ellis’s other great comic creation of the 1990s, Spider Jerusalem from Transmetropolitan.)

Planetary was part of a 1990s reappraisal of the pulps that gave us Mike Mignola’s Hellboy, Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentleman, Frank Miller’s Sin City, and more. In 1997, Moore wrote this about Hellboy, which is also true of Planetary avant la lettre:

The history of comic-book culture, much like the history of any culture, is something between a treadmill and a conveyer belt: we dutifully trudge along, and the belt carries us with it into one new territory after another. There are dazzlingly bright periods, pelting black squalls, and long stretches of grey, dreary fog, interspersed seemingly at random. The sole condition of our transport is that we cannot halt the belt, and we cannot get off. We move from Golden Age to Silver Age to Silicone Age, and nowhere do we have the opportunity to say, “We like it here. Let’s stop.” History isn’t like that. History is movement, and if you’re not riding with it then in all probability you’re beneath its wheels.

Lately, however, there seems to be some new scent in the air: a sense of new and different possibilities; new ways for us to interact with History. At this remote end of the twentieth century, while we’re further from our past than we have ever been before, there is another way of viewing things in which the past has never been so close. We know much more now of the path that lies behind us, and in greater detail, than we’ve ever previously known. Our new technology of information makes this knowledge instantly accessible to anybody who can figure-skate across a mouse pad. In a way, we understand more of the past and have a greater access to it than the folk who actually lived there.

In this new perspective, there would seem to be new opportunities for liberating both our culture and ourselves from Time’s relentless treadmill. We may not be able to jump off, but we’re no longer trapped so thoroughly in our own present movement, with the past a dead, unreachable expanse behind us. From our new and elevated point of view our History becomes a living landscape which our minds are still at liberty to visit, to draw sustenance and inspiration from. In a sense, we can now farm the vast accumulated harvest of the years or centuries behind. Across the cultural spectrum, we see individuals waking up to the potentials and advantages that this affords.

It’s one of those books where, like Ezra Pound imagined, an immersion in the old unlocks the artists’ imagination in understanding the present and future. Everything with a potential to blend the old and new is taken seriously. Aboriginal folk songs become secret keys to alternate dimensions. Jules Verne stories butt up against modern Hong Kong action movies. Monsters, magic, mushrooms all turn out to be coded pathways to better understand time and space.

It’s also a beautiful book. John Cassaday and Laura Martin, who later teamed up for Astonishing X-Men, Star Wars, and more, give every new landscape and character their own allusive twist. And all the allusions are less specific quotations than they are vectors to a general region of the cultural unconsciousness. You recognize a nod to Jim Steranko without knowing it’s Steranko. You can grasp the archetype without knowing the particular. It’s rewarding on a deep read without rejecting a naive one in the slightest.

I asked Abraham Riesman1, a writer and editor at Vulture, to say something smart about Planetary.

The closest comparison piece for Planetary in my young life would probably be, oddly enough, The Simpsons. I engaged with both before I had read or watched most of the texts that they were building upon, yet that somehow didn’t stop them from being utterly gripping stories on their own. The key difference is that Planetary, rather than simply producing satires of existing genres and works, served to point you in the direction of those genres and works. When you read of Doc Brass, you wanted to learn more about Doc Savage. When you visited Science City Zero, you wanted to take a subsequent trip to the video store (we still had such things when the series launched) and pick up DVDs depicting the colossal women and insectoid men of the 1950s. That’s no easy trick to pull off. And through it all, Ellis, Cassaday, and Martin made sure that you were meeting real people on these archaeological journeys. Consider, for example, Planetary/Batman: Night On Earth, one of the greatest Batman stories ever told. Sure, there are expert gags about the Adam West and Frank Miller eras, but the crux of the story comes when one of the dimensionally displaced Batmen tells a scared renegade metahuman that the goal of power is to make the less powerful feel taken care of. A story like that didn’t need such tender humanity, but the fact that it did is what will make sure it — like so much of Planetary — will remain accessible to anyone who’s ready to learn about what made the 20th century weird.

The century conceit lets Planetary loosen itself from the conceits of superhero comics. And because of how Planetary managed its mythology/anthology balance, it turns out to work best in single issues and as an entire whole. Unlike almost all the other comics produced at the turn of the century, it doesn’t break down neatly into arcs and trade paperbacks. In this way it keeps faith with the past and the future.

It’s a book from top to bottom that’s stubbornly resistant to the present, while also feeling perfectly contemporary. It’s weird and opaque, and you can’t shake the feeling that the writers and artists’ conception of it changed from year to year and month to month, but it keeps pulling you along. I might recommend other books first, I might think of other characters and stories more quickly, but there’s no comic I can think of that I love more than I do Planetary.

Stay Connected