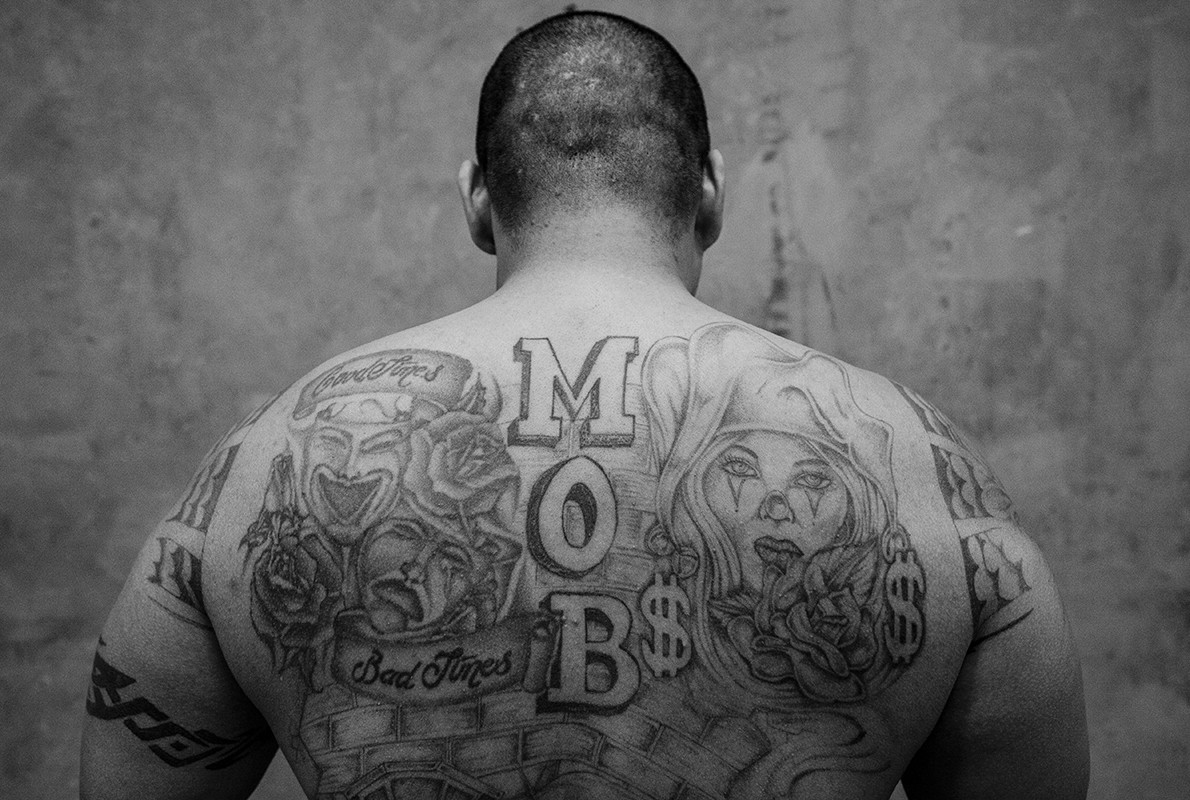

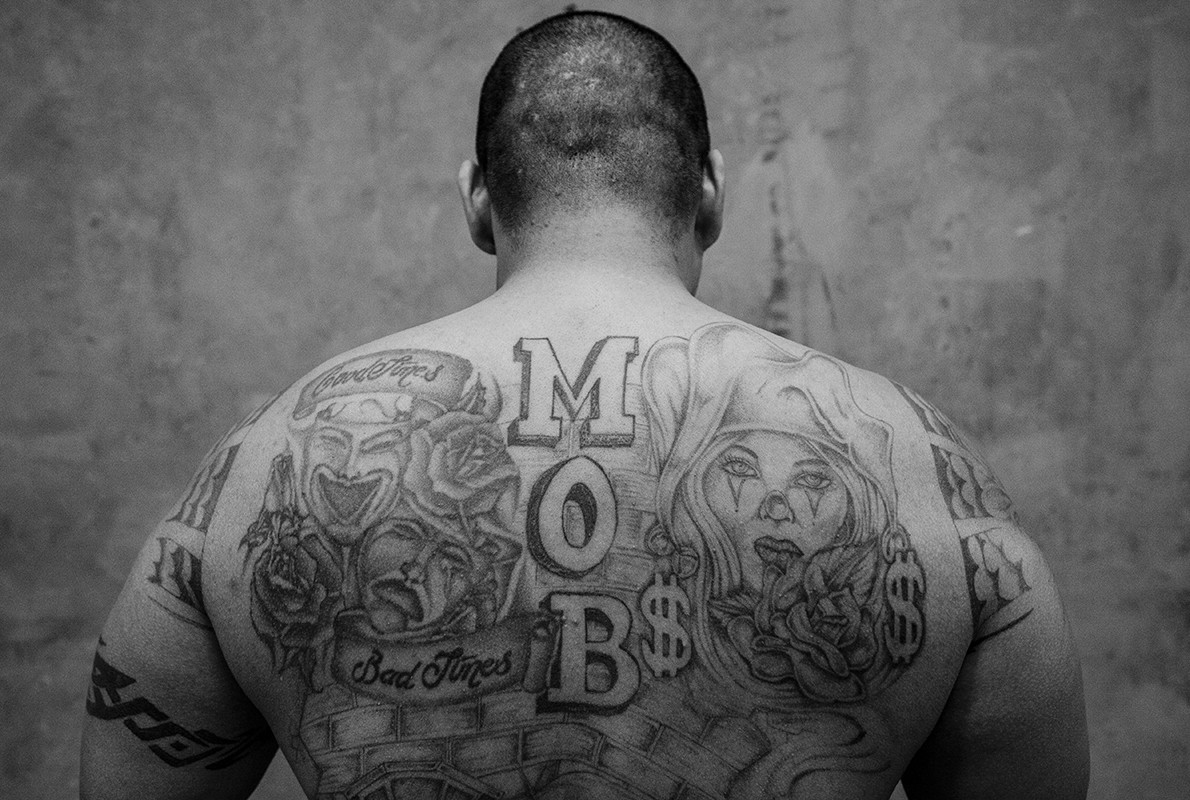

People are fascinated by prison tattoos. (I include myself in “people.”) This post at Mental Floss tries to spell out their meanings. The Economist’s Wade Zhou has crunched their numbers. And for The Marshall Project, Joseph Darius Jaafari digs into their technologies and economies: how they are made and how they circulate.

In Reddit threads and YouTube videos, former inmates describe the painstaking task of making tattoo machines and colored ink. Prisoners take apart beard trimmers or CD players to get at the tiny motor, which they can adapt to make the tattoo needle go up and down quickly enough. (Tattoo artists who use beard trimmers can quickly put the shaver back on and trick guards searching for contraband.)

The needle itself is often made from a metal guitar string split in two by holding it over an open flame until it snaps in half, creating a fine point. The springs inside gel pens can also flatten into needles.

One former prisoner who now runs a tattoo shop said he used to make black ink by trapping soot in a milk carton placed over a burning pile of plastic razors or Bible pages. He would mix the leftover ash and soot with a bit of alcohol (for hygienic purposes). To get color, some inmates use liquid India ink that family members buy from arts and crafts stores.

Why Bible pages, I wonder? Is it an availability thing or a ritual thing? Or both?

An emerging genre:

“When I would shower, I would take my clothes and wash them, people thought it was funny, but it was really a way for me not to get my own clothes robbed being there was no jump suits,” [Jason A.] wrote in a 1-star review of Rikers. “Food tasted like wet noodles and grill gristle…. I later learned to get a muslim halal card, and a jewish card, and know the kitchen staff to see which card would get me a better meal for the day.”…

In reviewing the Wayne County Jail, Athena Kolbe, a Detroit social worker, says her aim was twofold: first, she wanted potential visitors to “be prepared for it mentally when you go into it.” Second, “when you come out of it, know that all that disrespect you experienced, everybody else is also experiencing that. It’s not just you.”

This is what you need to know might be the best feature of any good review, and is arguably most essential when you don’t have a lot of choice in the matter. Not just jails, but hospitals, homeless shelters, emergency psychiatric services — there is a fair amount of official information, and there has always been informal word-of-mouth, but not many opportunities to get frank advice or to tell your story. Not much to make the experience anything but lonely and terrifying.

Today is a weird day for human-interest stories about bank robbers.

The New York Times highlights Shon R. Hopwood, a former bank robber who studied law in prison, successfully petitioned on behalf of another prisoner in a Supreme Court case his team won 9-0, and will soon be a clerk for the DC circuit federal appeals court, “generally considered the second most important court in the nation, after the Supreme Court”:

The judge Mr. Hopwood worked for last summer said he deserved his 147-month sentence. “He used a weapon in some of those robberies, and that justified a very heavy hit,” said Judge John C. Coughenour of Federal District Court in Seattle. “But everybody we sentence has the potential to turn their life around.”

Meanwhile, one state south in Oregon:

Authorities in Oregon say a homeless man who held up a bank for $1 was just looking for a way to go to jail so he could receive free health care.

According to Clackamas County sheriff’s deputies, 50-year-old Tim Alsip entered a Bank of America in Southeast Portland last Friday morning and handed the teller a note that read, “This is a holdup. Give me a dollar.”

I know he’s a busy man, but it would be remarkable if Mr. Hopwood could drive from Seattle to Portland and find a way to help Mr. Alsip be relegated to an appropriate facility.

Stay Connected