Lili Loofbourow on that great symbol of capitalism, now hollowed out by (mostly) private equity and (partly) changing consumer habits:

They aren’t easy to physically dispense with, malls.

It’s no surprise, then, that people are desperately trying to find new uses for them. The afterlife of a dead mall is interesting. Schools are moving into malls; some students are completing high school in a converted Macy’s in Vermont. A Dillard’s in Texas is now a radio station. Malls are becoming home to community colleges and libraries and offices. The Eastmont Town Center in Oakland, California, is home to a Center for Elders’ Independence, Social Security offices, and a lab.

These efforts are noble and good. They are also—and can’t help but be—anti-makeovers. Malls were made to be malls. This means every effort to repurpose a mall becomes a fascinating performance of architectural insufficiency, of a bespoke thing being wrenched into a different, and more practical, and less entertaining, function. It’s not that you can’t have schools in malls—or libraries, or social services. It’s that malls, being temples to consumerism, were tailor-made to be exactly what they were. Trying to square-peg another operation amid the former makeup counters beside onetime dressing rooms makes the result seem impoverished, weird, jangled. The erosion of detail is essential, but it makes the space grim.

Americans get nervous when symbols change. If the American grocery store was, among other things, deployed as an active rebuke of Soviet scarcity in the Cold War, the American department store was a serene display of endless availability. There were more kinds of makeup than anyone could possibly want, and they all had loyalists. Can we adapt to a new idea of the mall, the way old maritime warehouses turned into loft-living for gentrifiers? Should we? A stroll through these deserts finds dots of life poking through: mom and pop stores offering to repair watches or do your dry cleaning or your hair. I visited the Eastmont Town Center recently to see what it looked like in its new incarnation as a hub for seniors and Social Security and a “self-sufficiency center” where an anchor store used to be. A security guard stopped me at the entrance: Without an appointment and a specific destination in hand, she would not let me in. It puzzles me that the building is less accessible as the site of a library than it was as a mall, but I love the idea of a mall serving people in need. Still, the new configuration isn’t scratching the itch a mall did—at least according to other nostalgic mallgoers who have tried to haunt its halls. As one Yelp review reads: “Not enough stores, too many social services.”

“Americans get nervous when symbols change” — I’m going to be thinking about that for a while.

Something I think about a lot is if they remade Back to the Future today. Marty would travel back in time to 1992, and probably accidentally invent dubstep or something. But if he and Doc still met in the parking lot at the shopping mall, it would be a very different, much more haunted place. And the time machine wouldn’t suddenly crash into pine trees, but would appear near the mall’s peak in popularity. The scene from 1955 where Marty marvels at the officious gas station attendants would be replaced by one of Marty at the mall, amazed at the sheer number of people shopping, walking, letting themselves see and be seen at the outlet that in his time is now home to a plasma bank.

(Hi, this is Tim Carmody filling in for Jason this week. Hope you all have had a lovely holiday and are ready for more bloggy goodness here at kottke dot org.)

For a variety of reasons, I recently found myself inside a legal marijuana dispensary for the first time. I wasn’t sure exactly what I expected the retail experience to be like — a liquor store? a coffee shop? a used car lot? the paraphrenelia shops I first checked out as a teenager? — but I was nevertheless surprised.

The closest analogy I can think of is a jewelry store. There was pretty decent security, including a whole separate room for customers to check in, and everything was presented in a secure display case. A salesperson walked you through the samples to answer questions, guide you in one direction or another, and take your order, while the order itself was filled in a secure area away from the showroom. The other shopping experience I’ve had that’s similar was buying medical equipment, which makes some sense given the origin of a lot of retail dispensaries in the medical marijuana era. You could also say it’s a little like a pharmacy (which again, is probably unsurprising).

Some of the setup of dispensaries is a function of legal regulations (do you need to check IDs and differentiate between medical and recreational customers?) and some of it solves some practical problems (weed is expensive and there’s still a viable aftermarket, so you are in principle a target for theft).

But it’s also a question of culture: who’s involved in the transaction as a seller and as a buyer, and what are their assumptions and competencies that they’re bringing to the party (so to speak)?

For instance, today Lifehacker (I know, right?) has a short interview with an entrepreneur who runs dispensaries in California, who comes out of the restaurant industry. (It’s titled “How to Break Into the Legal Weed Industry” which is, I think, a very rare kind of service journalism, or more likely, a simple explainer masquerading as service journalism.)

“My entrance into the cannabis industry was several years ago,” said Captor Capital’s Adam Wilks, who operates dispensaries in California, where he reported the business is “smooth sailing” for the most part. “I had worked in the restaurant industry for major brands, including Pinkberry. When I entered, we were just starting to see traction with federal legalization pushes like the SAFE Banking Act and statewide sweeps. I think I entered during the ‘sweet spot’ period where there was still a lot of excitement about an emerging industry and a lot of big money wasn’t quite ready to take risks. Now, everyone is funneling into cannabis.”

Now, a restaurant is a very different industry and has a very different culture than a pharmacy or jeweler or the marijuana sales industry as it’s existed pre-legalization. One might expect a very different retail experience by people with those competencies and expectations. As people from other industries enter the world of cannabis, an amalgamated lingua franca might start to emerge, or you might get very differentiated experiences in different markets.

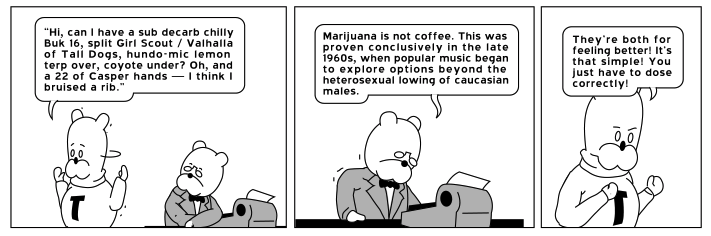

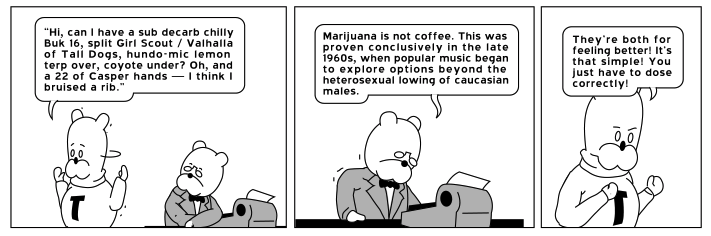

There’s an Achewood comic titled “Marijuana is not coffee” that’s about five years old now that compares the emerging legal cannabis industry to coffee shops — not just ubiquitous but gentrified, made completely palatable by the American retail industry’s ability to turn anything into a consumer-friendly experience. The characters also imagine a whole cannabis-specific jargon, on the model of coffee talk. Here’s an excerpt:

I don’t know; someone with more than a passing acquaintance with these shops and their alternatives will have to do the full anthropology. But it does seem to me that with the legalization of marijuana, we are in the process of changing more than who is allowed to get high and who is allowed to get paid without being punished.

Maybe we’ve got it all wrong about this whole capitialism thing. “In every substantive sense, employees of a company carry more risks than do the shareholders. Also, their contributions of knowledge, skills and entrepreneurship are typically more important than the contributions of capital by shareholders, a pure commodity that is perhaps in excess supply.”

Stay Connected