Yes, barbed wire fenced cows but also provided telecommunications

Barbed wire is one of the most important inventions of the past 150 years. It tamed the Wild West and solidified the concept of land ownership in America. Tim Harford, author of Fifty Inventions That Shaped the Modern Economy, writes:

After Europeans arrived and pushed west, the cowboys roamed free, herding cattle over the boundless plains.

But settlers needed fences, not least to keep those free-roaming cattle from trampling their crops. And there wasn’t a lot of wood — certainly none to spare for fencing in mile after mile of what was often called “The American Desert”.

Farmers tried growing thorn-bush hedges, but they were slow-growing and inflexible. Smooth wire fences didn’t work either — the cattle simply pushed through them.

Barbed wire changed what the Homestead Act could not.

Until it was developed, the prairie was an unbounded space, more like an ocean than a stretch of arable land.

Private ownership of land wasn’t common because it wasn’t feasible.

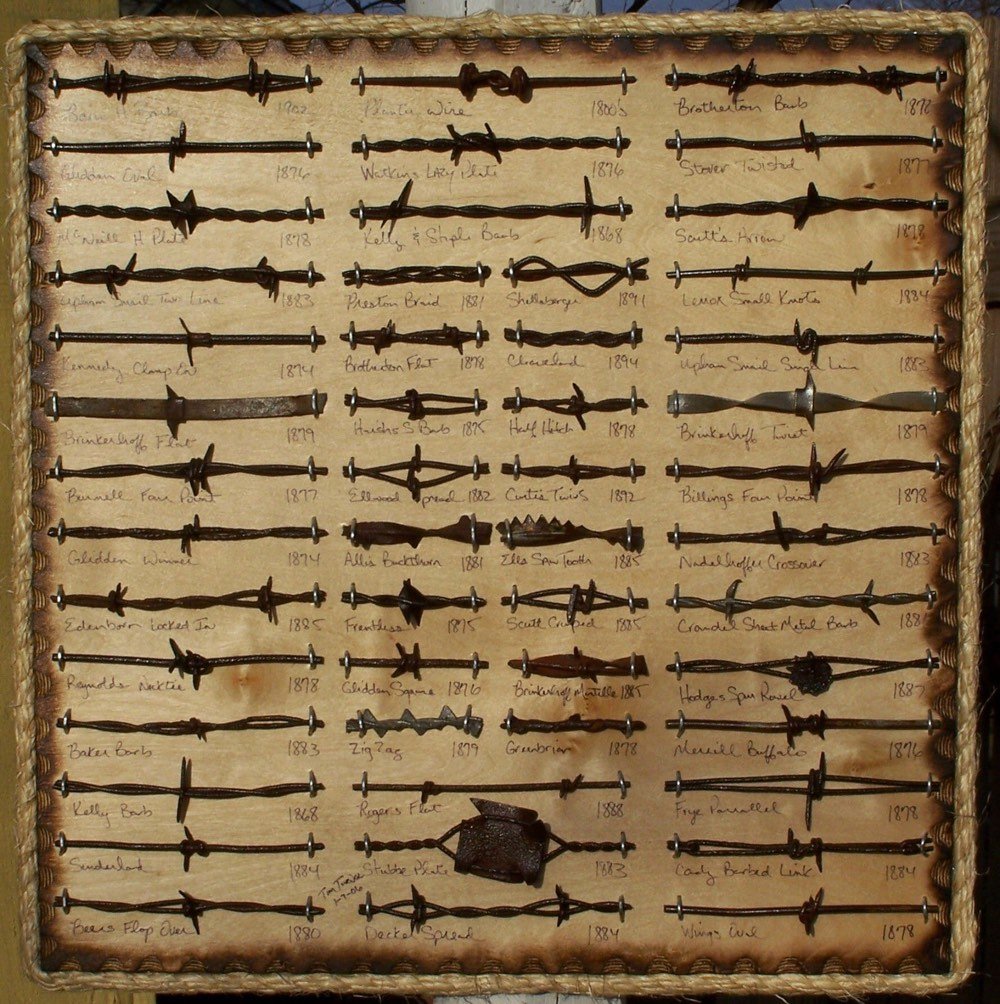

With demand came fierce competition; there were dozens of different types of barbed wire:

Just two years after Joseph Glidden patented his design for barbed wire in 1874, another of the 19th century’s great inventions burst onto the scene in the form of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. The two world-changing technologies would combine in a surprising way in the western United States. Because of the expense of running dedicated telephone services over long distances, some farmers opted to run their telecommunications over the hundreds of thousands of miles of barbed wire criss-crossing the land.

It was in building the network connecting homestead to homestead that the farmers’ ingenuity came to the fore. Instead of erecting new poles and wires, many either ran phone wires along the top of wooden fence posts or used the barbed wire itself to carry signals. The latter hardly worked as well as insulated copper wire, but with the lines already in place, installation and operating costs could be kept to a minimum. By one estimate, service ran a mere $3 to $18 a year, far less than the regional phone companies charged, and labor for maintaining the network was supplied by volunteers.

So cool. I’m reading A Mind at Play right now. It’s a biography of Claude Shannon, “the architect of the information age”. As a boy, Shannon wired the half-mile stretch of barbed wire fence between his family’s farm and a friend’s house:

He charged it himself: he hooked up dry-cell batteries at each end, and spliced spare wire into any gaps to run the current unbroken. Insulation was anything at hand: leather straps, glass bottlenecks, corncobs, inner-tube pieces. Keypads at each end — one at his house on North Center Street, the other at his friend’s house half a mile away — made it a private barbed-wire telegraph. Even insulated, it is apt to be silenced for months in the ice and snow that accumulate on it, at the knuckle of Michigan middle finger. But when the fence thaws and Claude patches the wire, and the current runs again from house to house, he can speak again at lightspeed and, best of all, in code.

In the 1920s, when Claude was a boy, some three million farmers talked through networks like these, wherever the phone company found it unprofitable to build. It was America’s folk grid. Better networks than Claude’s carried voices along the fences, and kitchens and general stores doubled at switchboards.

(via mr)

Update: See also the Devil’s Rope episode of 99% Invisible. (thx, dave)

Stay Connected