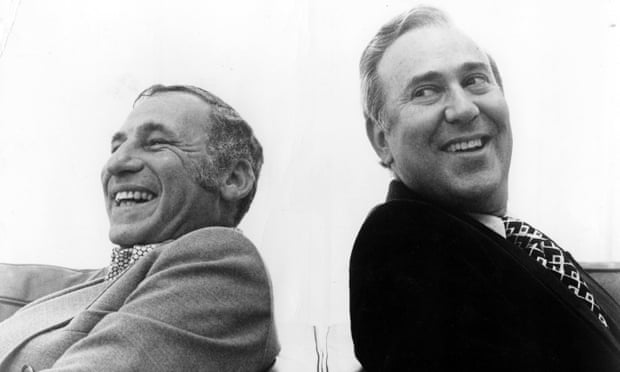

Say Yes: Mel Brooks at 95

Mel Brooks was born in 1926; he will (god willing) turn 96 in June. That’s something of a non-Newtownian age — the length of his career warps our usual generational physics.

Let’s try to put it in context. Brooks was born in the same year as Queen Elizabeth (II, don’t be cheeky), Marilyn Monroe, and John Coltrane. He’s old enough to have served in World War 2 (which he did), and that he was already in his 40s when he became a filmmaker, with The Producers. People sometimes point out that Barbara Walters, Martin Luther King Jr., and Anne Frank were born in the same year, to note how exact contemporaries can belong to such widely different time periods — yet Brooks is three years older than that trio.

Brooks was somehow a contemporary to almost everybody — I was surprised recently, reading the Tom Stoppard biography, that Brooks and Stoppard spent time together in New York City the early 60s, when Stoppard was a young theater reporter and Brooks was performing with Carl Reiner. That’s a fifth of the comic DNA of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead right there. (Yet, somehow, Brooks is eleven years older than Stoppard.)

One of my favorite clips of Brooks is a 1975 appearance on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show where he essentially takes over the show (the YouTube video is 53 minutes long).

Brooks has a new book out, a memoir titled All About Me! My Remarkable Life In Show Business. (I have not read it, but I want to.)

He’s done a requisite (funny, thoughtful) interview with Terry Gross for Fresh Air, where he shares some homespun wisdom:

I’m so grateful to be able to eat scrambled eggs and toast for breakfast and sometimes a roast beef sandwich for dinner. I’m so happy that I still have somewhat of an appetite. I’m having trouble sleeping. That’s a problem. But otherwise things are pretty good for being 95 and I’m getting around fairly well and my basic emotional attitude is still more positive than negative. I’m still looking forward to talking to people, to meeting people, to have dinner with people.

The book, too, seems to be more positive than negative; during the interview with Gross, she tries to prod him about moments of depression he mentions in his childhood, and he basically dismisses them. Alexandra Jacobs notes that Brooks “would prefer to kvell over the talents of his frequent collaborators Madeline Kahn, Gene Wilder and Carl Reiner, than linger on, or even mention, their departures from this crazy world.” In old age as in childhood, humor can be a lifeline.

It’s also a strategy. Michael Schulman touches on this in his interview with Brooks:

You have some wonderful stories of basically getting away with stuff at the studios.

I’d learned one very simple trick: say yes. Simply say yes. Like Joseph E. Levine, on “The Producers,” said, “The curly-haired guy—he’s funny looking. Fire him.” He wanted me to fire Gene Wilder. And I said, “Yes, he’s gone. I’m firing him.” I never did. But he forgot. After the screening of “Blazing Saddles,” the head of Warner Bros. threw me into the manager’s office, gave me a legal pad and a pencil, and gave me maybe twenty notes. He would have changed “Blazing Saddles” from a daring, funny, crazy picture to a stultified, dull, dusty old Western. He said, “No farting.” I said, “It’s out”… You say yes, and you never do it.

That’s great advice for life.

It is. Don’t fight them. Don’t waste your time struggling with them and trying to make sense to them. They’ll never understand.

Writing for The Guardian, Hadley Freeman has what’s probably the most comprehensive take on Brooks’s biography, and makes the best effort (although not entirely successful) to get past Brooks’s comic defense mechanisms.

Brooks’s story begins - as it did for so many American comedians of his generation, including Reiner - in a working-class Jewish family. “People say, ‘Out of the suffering of Jews, the need to laugh is critical for the survival of the race.’ But we didn’t become comics out of misery. We became comics because there are a lot of laughs in Jewish households. There’s always some wiseguy making cracks about how fat Aunt Sadie is, and it’s a need for that joy to continue that was the engine for all of us to become comics. It was fun being a little Jewish boy in a household with three older brothers and my mother; my aunt and my grandmother living next door,” he says.

Brooks also distinguishes between Jewish humor and New York humor, telling Schulman:

Yiddish comedy, or Jewish comedy, has to do with Jewish folklore. Sholem Aleichem, that kind of stuff. The mistakenly called “Jewish comedy” of the great comics—it was really New York. It was the streets of New York: the wiseguy, the sharpness that New York gives you that you can’t get anywhere else, but you can get it on the streets of Brooklyn. Jewish comedy was softer and sweeter. New York comedy was tougher and more explosive. There’s some cruelty that you find in New York humor that you wouldn’t find in Yiddish humor. In New York, you make fun of somebody who walks funny. You never find that in Sholem Aleichem. You’d feel pity. There’s no pity in New York. There’s reality and a brushstroke of brutality in it.

In a way, what I think Brooks is describing is the ability to blend the traditional with the contemporary. It’s a kind of Jewish humor, but it’s not old Jewish humor. This is essentially the gag behind the 2000 Year Old Man — a character who has experienced the tumults and tragedies of history, but can talk about them as if they happened to himself and his neighbors just last week:

Reiner: Did you know Jesus?

Brooks: Thin lad, right? Wore sandals? Hung around with 12 other guys? They always came into my store. Never bought anything, just asked for water.

And maybe that’s why Brooks feels both so eternal and so contemporary. It’s right there; it’s in the jokes.

Socials & More