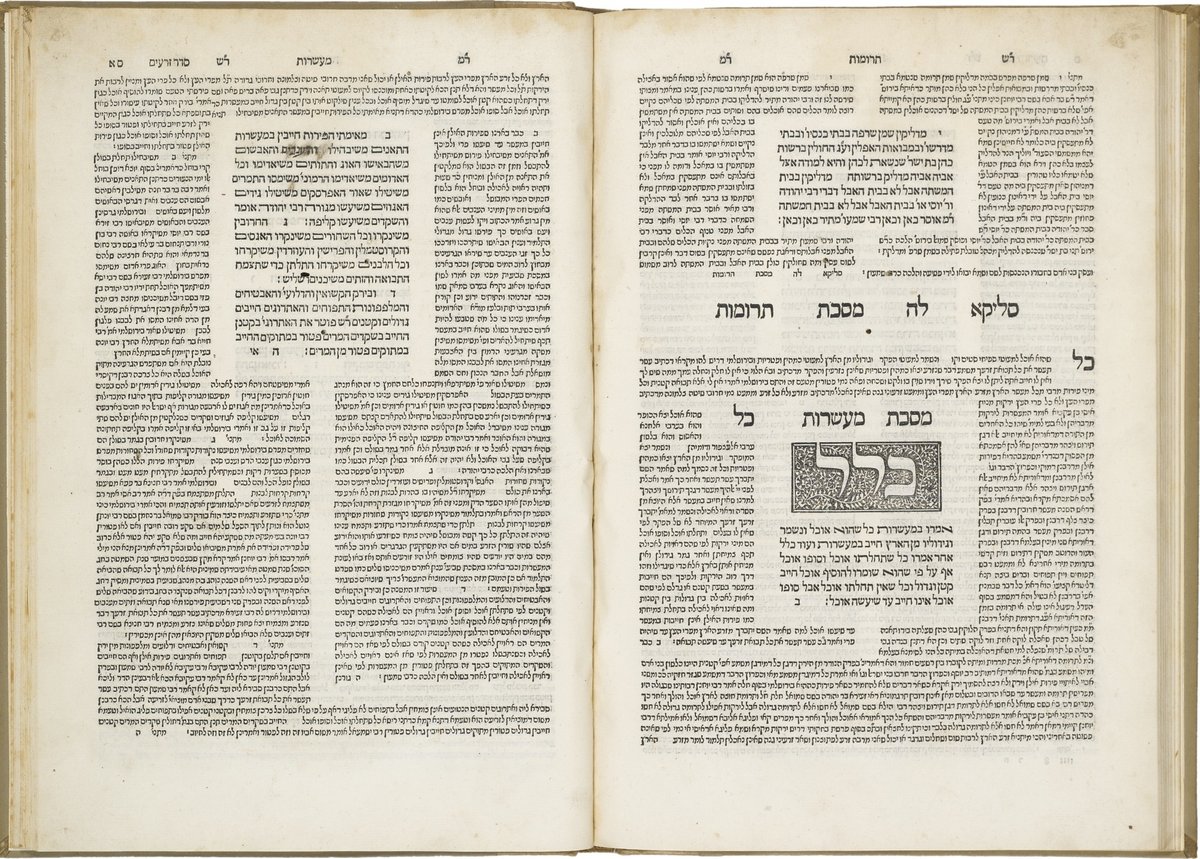

Putting the Talmud online

Sefaria is a free online resource for Jewish texts, specifically the Talmud, which (amazingly) wasn’t previously easily available online. This Washington Post article describes the effort behind getting the texts and their translations up and on the web.

The Talmud is notoriously hard to follow, even if you understand Aramaic. For most readers, a straight translation will not be useful, as additional, contextualizing information, based on expertise with the tradition and text, is necessary to follow the arguments.

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz created one of the three seminal works in this regard, but it was under copyright and being published by Koren Publishers.

After a prolonged negotiation process, and a substantial gift from the William Davidson Foundation, Sefaria was able to secure the copyright. Then, they ceded their rights and made it available free to the public, a move common to nature conservancies but vanishingly rare in the publishing world, since copyright and exclusivity are major guarantors of revenue.

“Sefaria argues that these texts are our collective heritage; therefore they should be available to everyone for free,” Sarna said.

“You have access to something that Jews, for hundreds of years did not, whether it was banned, or they didn’t understand, or they couldn’t buy books,” said Rabbi Levitansky.

Making the texts available in digital form, for free, enables a lot of new use cases for the Talmud, from using code to find “fuzzy links” between different bits of the texts, to democratizing the audience. Younger, less observant readers now have access to a wider range of textual material and discussion than they did before. The text also serves as a discussion platform: its most-viewed “source sheet” is called “Is One Permitted to Punch a White Supremacist in the Face?”

I don’t know whether, as Joshua Foer has it, a digital version of the Talmud is an “advance akin to the writing down of the oral tradition after the fall of the Second Temple in A.D. 70 and the advent of the printing press.” It is, however, a very welcome transformation of a text that’s accustomed to great transformations.

And it also gets back to something I remember from the great In Our Time episode on the Talmud: that Talmud isn’t a book you read so much as a thing you do — or as Foer says, a “giant, unending conversation that spans millennia, continents, and is very much still going on to this day.”

Stay Connected