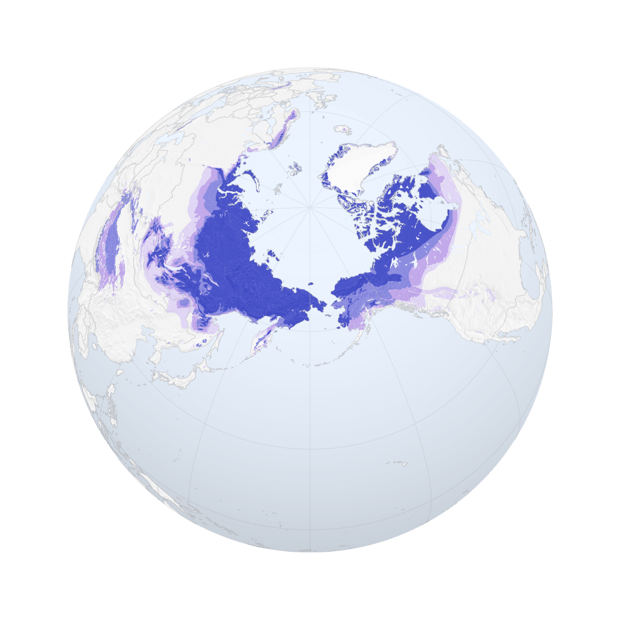

Life in the far north

Two stories about human settlements in the arctic north caught my eye this week. The first is about polar bear patrols in western Alaska, who try to keep bears away from towns without hurting or killing them.

“It would have been better if we would have hazed him more towards the airport, instead of through town,” says Casey Tingook, Oxereok’s nephew. He also suggests that the snowmobile passenger carry the team’s radio instead of the driver to reduce the interference from engine noise. The discussion turns to communication and how to give the village the all-clear once a bear is gone. It’s decided that phone calls should go out to houses on the fringes of town, where the bears are most likely to appear, so word can spread naturally inward from there. The men talk through their options for another few minutes and then head back out into the darkness to face their next bear.

The second story explains how melting permafrost has worsened a housing crisis throughout the Arctic region, specifically in Canada’s Nunavut territory:

In Iqaluit, the capital of the Canadian province Nunavut, a good home is hard to find. An efficiency apartment runs around $2,000 a month, while a two-bedroom house will cost about $3,500. These New York prices are shocking in a small, remote town of about 7,500 people. And there still aren’t enough homes for everyone….

The main problem has to do with soil moisture. When water freezes, it expands, so the ground rises; conversely, when it thaws and the soil contracts, the ground sinks. Permafrost in many places across the Arctic is now locked in a pattern of thawing and refreezing each new season, when once it remained steady. The ground rises and sinks with each change in the weather.

Across the Arctic, roads and buildings buckle along with the ground. Russia is home to some of the largest cities in the Arctic, which are undergoing profound changes because of permafrost thaw. In the coal-mining town of Vorkuta, about 40 percent of buildings have become deformed from changes in the ground. In Norilsk, the largest city built on permafrost, about 60 percent of buildings have been damaged by permafrost thaw, and 10 percent of the houses in the city have been abandoned. Most of the changes happen gradually, but they can render buildings dangerous once they begin; a few years ago in Norilsk, a cement slab broke a doctor’s legs when a building shifted and crumbled.

I guess I’m continually amazed at how modern humans live in worlds that weren’t built for them, but find a way to adapt to them anyways. And while the arctic is an extreme example, it’s also a reminder that — not to get too existential — none of this was built for us. And none of us were made for this. We are not at home here.

Socials & More