A visual history of light

From the Atlantic, a quick visual history of human-created light sources over the past ~400,000 years, from wood fires to candles to the electric light.

3,000 BCE: The “rushlight” candle is invented in Ancient Egypt. It is made of a pithy stalk of rush soaked in animal fat.

1500 BCE: Babylonian/Assyrian lamps are created from olive or sesame oil. They had a linen wick and were fashioned from stone, terracotta, metal, or shells.

100 CE: The Romans create the tallow candle, which has a small wick with a thick, hand-formed layer of tallow.

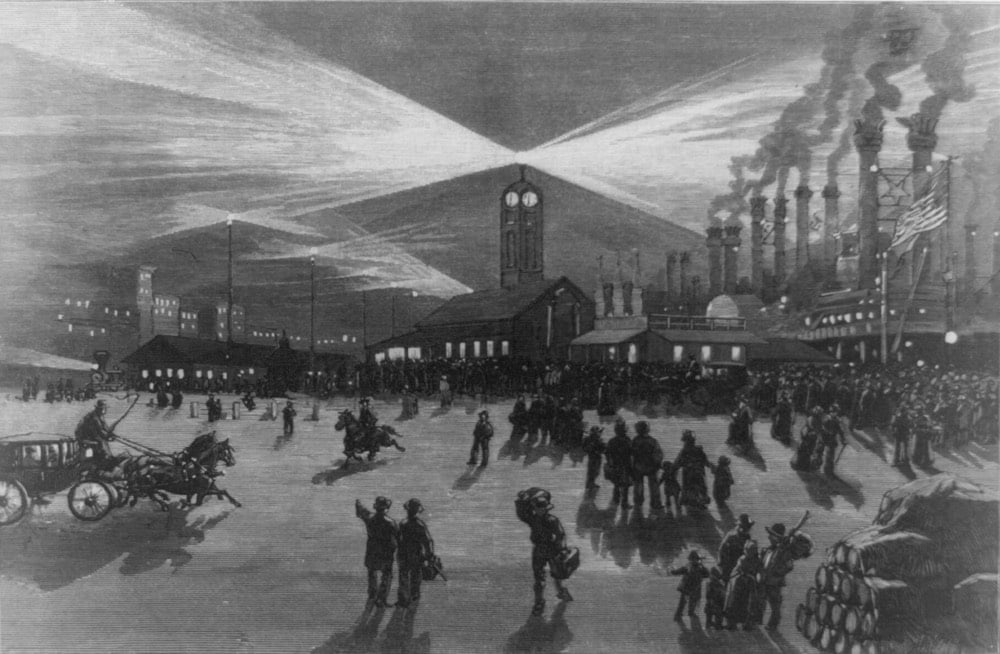

One of the more interesting inventions along the way was the moonlight tower. In the early days of electric lights, mimicking the bright light of the Moon was one of the ways that towns chose to light their streets.

Humans, too, found the high-slung orbs to be as disorienting as they were ethereal. As tall as the towers were, they still left shadows in their wake — shadows tinged with sharp blue light, Freeberg notes, which left pedestrians “dazed and puzzled.” Foggy evenings, combined with the air pollution of a newly industrialized America, could thrust all of Detroit into effective darkness — meaning, Freeberg writes, that “Detroiters could only speculate about the lovely sight that their lights must be creating as they shone down on the blanket of mist and soot that smothered the city.” Even during occasions when the fog broke enough to allow some light to penetrate to the streets below, “many found themselves groping along sidewalks in an eerie gloom.”

In the end, the many costs of the artificial moonlight outweighed its beauty and poetry. The structures meant to inspire awe among outsiders ended up inspiring, ultimately, something more akin to pity. (“It appears to me,” one frank observer put it, “that you are taking a very expensive way of getting a minimum benefit from the electric lights.”)

Socials & More