kottke.org posts about email

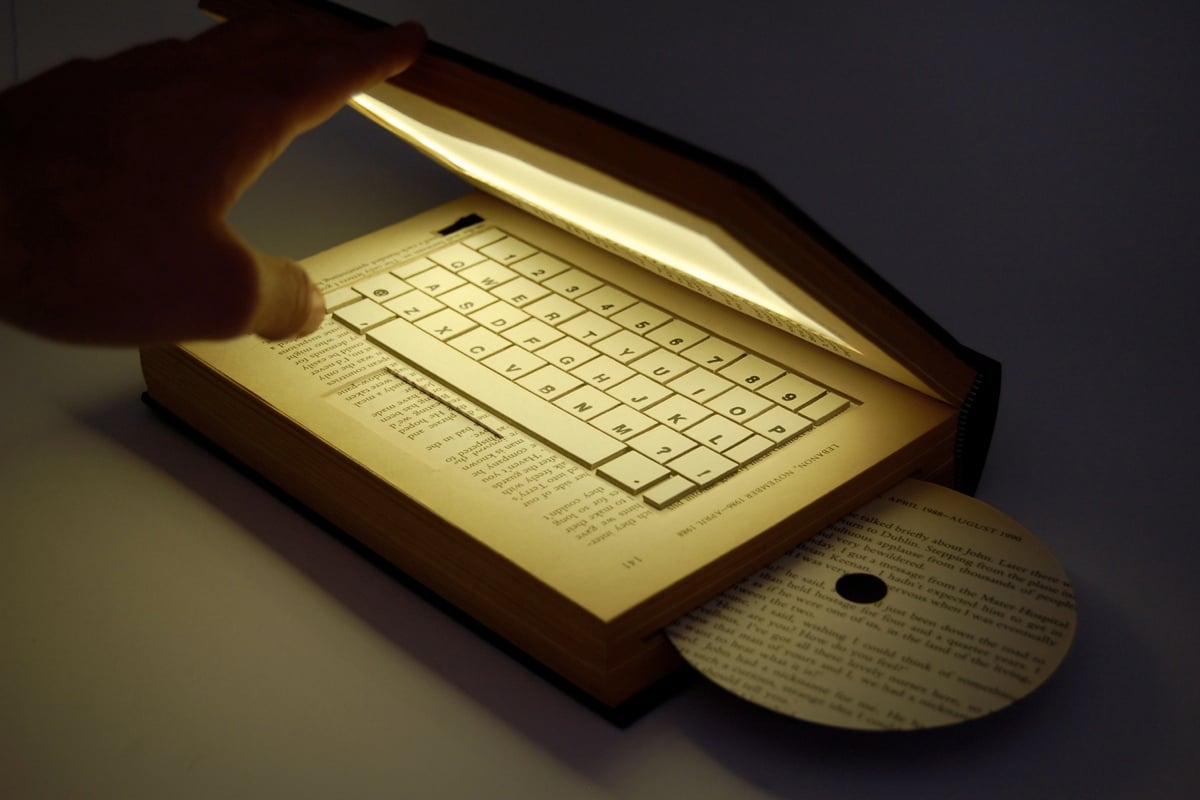

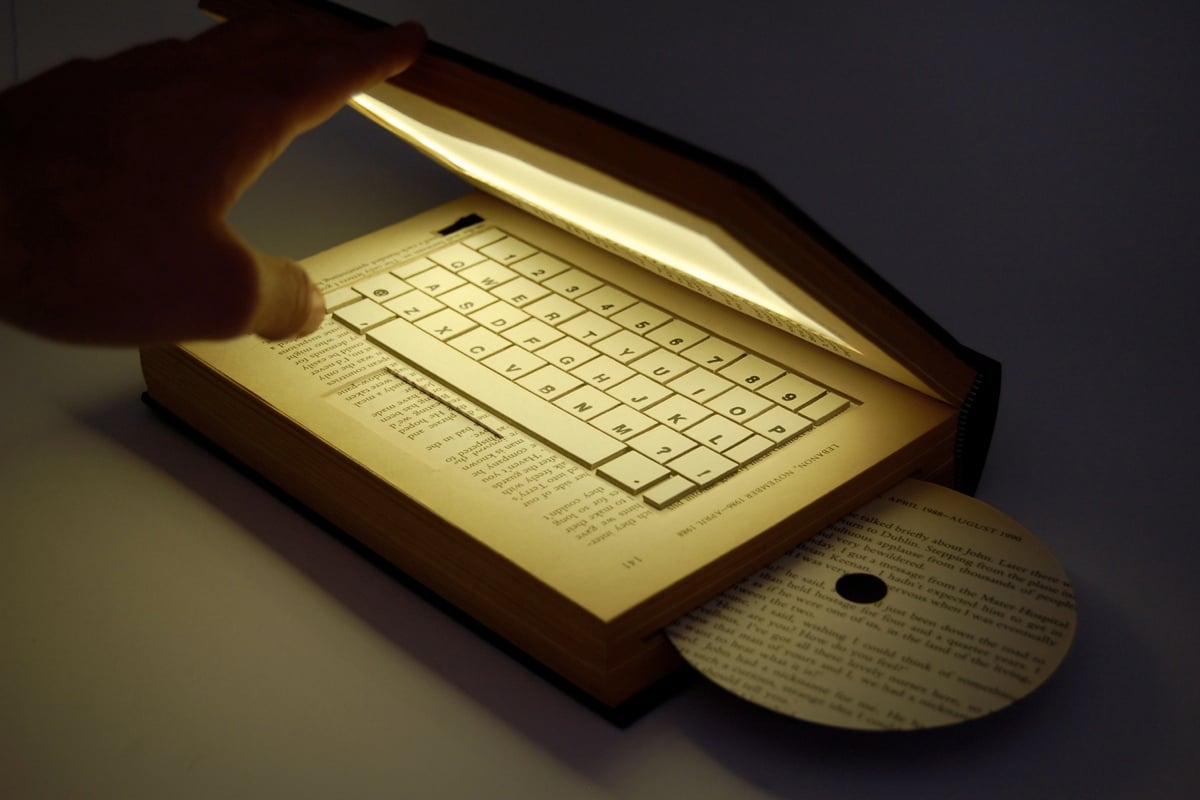

From Demetria Glace and photographer Emilie Baltz, The Leaked Recipes Cookbook is a collection of over 50 recipes from the world’s biggest email leaks and hacks.

This book compiles major email leaks of the past 15 years through the theme of cooking. Part reportage, part cookbook, it showcases over 50 recipes for breakfast, dips, main dishes, sides and desserts. The recipes come from emails released after having been hacked, leaked, breached and uploaded by governments as part of large-scale investigations. Indulge in once-confidential instructions, shared by staff from the world’s most influential companies, government workers linked to Hillary Clinton’s emails and more.

Mmm, Butter Emails. (via a thing or two)

I’ve shared this here before, but one of my favorite Old Weird Internet stories is Trey Harris’ The case of the 500-mile email. If you’ve ever worked in tech support or system administration (or have been on the receiving end of stories by people doing that work), a common trope features someone (usually a boss of some sort) thinking they’ve stumbled across a bug when in fact it’s user error. That’s not where this story goes…

I was working in a job running the campus email system some years ago when I got a call from the chairman of the statistics department.

“We’re having a problem sending email out of the department.”

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

“We can’t send mail more than 500 miles,” the chairman explained.

I choked on my latte. “Come again?”

“We can’t send mail farther than 500 miles from here,” he repeated. “A little bit more, actually. Call it 520 miles. But no farther.”

“Um… Email really doesn’t work that way, generally,” I said, trying to keep panic out of my voice. One doesn’t display panic when speaking to a department chairman, even of a relatively impoverished department like statistics. “What makes you think you can’t send mail more than 500 miles?”

“It’s not what I *think*,” the chairman replied testily. “You see, when we first noticed this happening, a few days ago—”

“You waited a few DAYS?” I interrupted, a tremor tinging my voice. “And you couldn’t send email this whole time?”

“We could send email. Just not more than—”

“—500 miles, yes,” I finished for him, “I got that. But why didn’t you call earlier?”

Read the whole thing if you’ve never had the pleasure.

Writing in Wired, Craig Mod expertly dissects both the e-book revolution that never happened and the quieter one that actually did:

The Future Book was meant to be interactive, moving, alive. Its pages were supposed to be lush with whirling doodads, responsive, hands-on. The old paperback Zork choose-your-own-adventures were just the start. The Future Book would change depending on where you were, how you were feeling. It would incorporate your very environment into its story—the name of the coffee shop you were sitting at, your best friend’s birthday. It would be sly, maybe a little creepy. Definitely programmable. Ulysses would extend indefinitely in any direction you wanted to explore; just tap and some unique, mega-mind-blowing sui generis path of Joycean machine-learned words would wend itself out before your very eyes.

Prognostications about how technology would affect the form of paper books have been with us for centuries. Each new medium was poised to deform or murder the book: newspapers, photography, radio, movies, television, videogames, the internet.

That isn’t what happened. The book was neither murdered nor fundamentally transformed in its appearance, its networked quality, or its multimedia status. But the people and technologies around the book all did fundamentally change, and arguably, changed for the better.

Our Future Book is composed of email, tweets, YouTube videos, mailing lists, crowdfunding campaigns, PDF to .mobi converters, Amazon warehouses, and a surge of hyper-affordable offset printers in places like Hong Kong.

For a “book” is just the endpoint of a latticework of complex infrastructure, made increasingly accessible. Even if the endpoint stays stubbornly the same—either as an unchanging Kindle edition or simple paperback—the universe that produces, breathes life into, and supports books is changing in positive, inclusive ways, year by year. The Future Book is here and continues to evolve. You’re holding it. It’s exciting. It’s boring. It’s more important than it has ever been.

This is all clever, sharply observed, and best of all, true. But Craig is a very smart man, so I want to push him a little bit.

What he’s describing is the present book. The present book is an instantiation of the future book, in St. Augustine’s sense of the interconnectedness and unreality of the past, future, and eternity in the ephemerality of the present, sure. But what motivated discussions of the future book throughout the 20th and in the early 21st century was the animating force of the idea that the book had a future that was different from the present, whose seeds we could locate in the present but whose tree was yet to flourish. Craig Mod gives us a mature forest and says, “behold, the future.” But the present state of the book and discussions around the book feel as if that future has been foreclosed on; that all the moves that were left to be made have already been made, with Amazon the dominant inertial force locking the entire ecosystem into place.

But, in the entire history of the book, these moments of inertia have always been temporary. The ecosystem doesn’t remain locked in forever. So right now, Amazon, YouTube, and Kickstarter are the dominant players. Mailchimp being joined by Substack feels a little like Coke being joined by Pepsi; sure, it’s great to have the choice of a new generation, but the flavor is basically the same. So where is the next disruption going to come from?

I think the utopian moment for the future of the book ended not when Amazon routed its vendors and competitors, although the Obama DOJ deserves some blame in retrospect for handing them that win. I think it ended when the Google Books settlement died, leading to Google Books becoming, basically abandonware, when it was initially supposed to be the true Library of Babel. I think that project, the digitization of all printed matter, available for full-text search and full-image browsing on any device, and possible conversion to audio formats and chopped up into newsletters, and whatever way you want to re-imagine these old and new books, remains the gold standard for the future of the book.

There are many people and institutions still working on making this approach reality. The Library of Congress’s new digital-first, user-focused mission statement is inspiring. The Internet Archive continues to do the Lord’s work in digitizing and making available our digital heritage. HathiTrust is still one of the best ideas I’ve ever heard. The retrenchment of the Digital Public Library of America is a huge blow. But the basic idea of linking together libraries and cultural institutions into an enormous network with the goal of making their collections available in common is an idea that will never die.

I think there’s a huge commercial future for the book, and for reading more broadly, rooted in the institutions of the present that Craig identifies: crowdfunding, self-publishing, Amazon as a portal, email newsletters, etc. etc. But the noncommercial future of the book is where all the messianic energy still remains. It’s still the greatest opportunity and the hardest problem we have before us. It’s the problem that our generation has to solve. And at the moment, we’re nowhere.

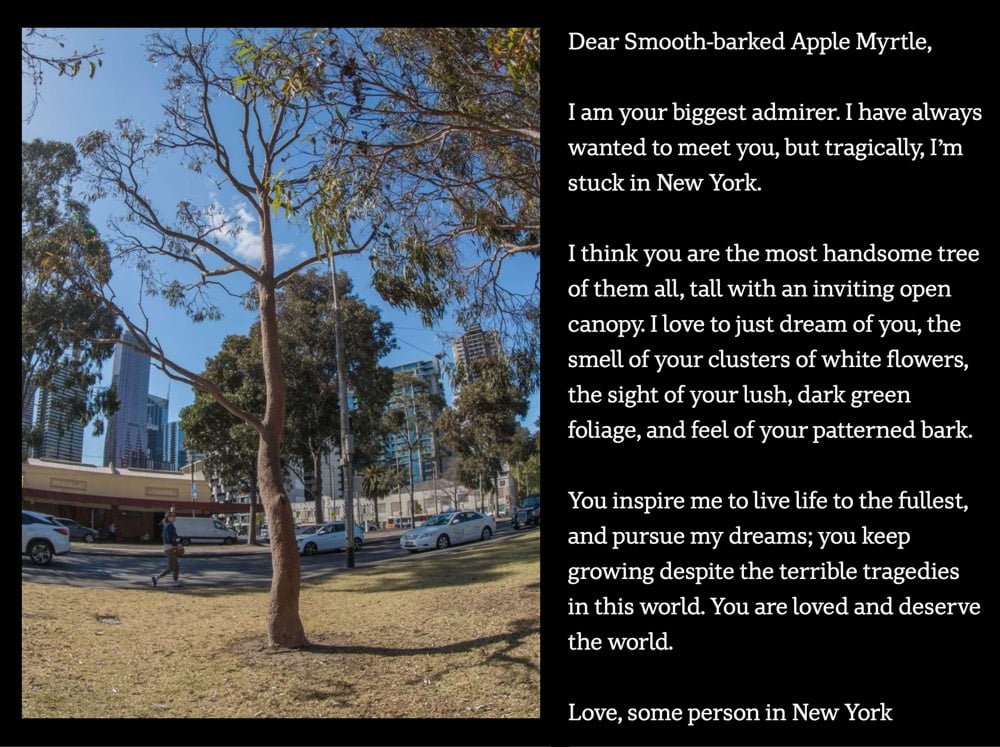

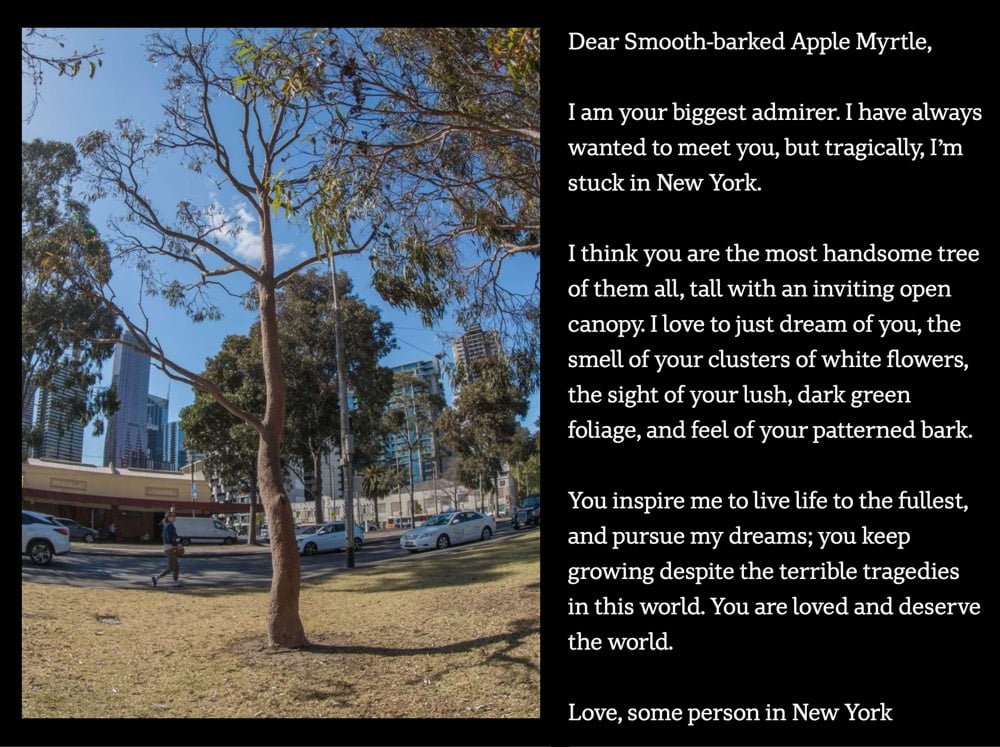

You might remember this 2015 Atlantic piece about what happened when Melbourne gave each of the city’s trees its own email address for reporting arboreal problems: people started writing love letters to the trees.

“My dearest Ulmus,” the message began.

“As I was leaving St. Mary’s College today I was struck, not by a branch, but by your radiant beauty. You must get these messages all the time. You’re such an attractive tree.”

This is an excerpt of a letter someone wrote to a green-leaf elm, one of thousands of messages in an ongoing correspondence between the people of Melbourne, Australia, and the city’s trees.

More than three years later, people are still writing. ABC News has collected some of the most interesting emails and presented them alongside photos of the trees they’re directed to.

Another admirer wrote to a Moreton Bay Fig tree:

You are beautiful. Sometimes I sit or walk under you and feel happier.

I love the way the light looks through your leaves and how your branches come down so low and wide it is almost as if you are trying to hug me. It is nice to have you so close, I should try to visit more often.

Ray Tomlinson, who implemented the first email system on the ARPANET (the Internet’s precursor) and decided on the @ symbol for use in email addresses, died on Saturday at the age of 74. From his biography at the Internet Hall of Fame:

Tomlinson’s email program brought about a complete revolution, fundamentally changing the way people communicate, including the way businesses, from huge corporations to tiny mom-and-pop shops, operate and the way millions of people shop, bank, and keep in touch with friends and family, whether they are across town or across oceans. Today, tens of millions of email-enabled devices are in use every day. Email remains the most popular application, with over a billion and a half users spanning the globe and communicating across the traditional barriers of time and space.

Still one of my favorite internet things: The case of the 500-mile email.

I was working in a job running the campus email system some years ago when I got a call from the chairman of the statistics department.

“We’re having a problem sending email out of the department.”

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

“We can’t send mail more than 500 miles,” the chairman explained.

I choked on my latte. “Come again?”

“We can’t send mail farther than 500 miles from here,” he repeated. “A little bit more, actually. Call it 520 miles. But no farther.”

“Um… Email really doesn’t work that way, generally,” I said, trying to keep panic out of my voice. One doesn’t display panic when speaking to a department chairman, even of a relatively impoverished department like statistics. “What makes you think you can’t send mail more than 500 miles?”

“It’s not what I *think*,” the chairman replied testily. “You see, when we first noticed this happening, a few days ago—”

“You waited a few DAYS?” I interrupted, a tremor tinging my voice. “And you couldn’t send email this whole time?”

“We could send email. Just not more than—”

“—500 miles, yes,” I finished for him, “I got that. But why didn’t you call earlier?”

“Well, we hadn’t collected enough data to be sure of what was going on until just now.” Right. This is the chairman of *statistics*. “Anyway, I asked one of the geostatisticians to look into it—”

“Geostatisticians…”

“—yes, and she’s produced a map showing the radius within which we can send email to be slightly more than 500 miles. There are a number of destinations within that radius that we can’t reach, either, or reach sporadically, but we can never email farther than this radius.”

Here’s a FAQ that addresses some of the questions the more technically inclined among you may have about this story.

I’m going to link again to Errol Morris’ piece on his brother’s role in the invention of email…the final part was posted a few hours ago…the entire piece is well worth a read. As is the case with many of his movies, Morris uses the story of a key or unique individual to paint a broader picture; in this instance, as the story of his brother’s involvement with an early email system unfolds, we also learn about the beginnings of social computing.

Fernando Corbato: Back in the early ’60s, computers were getting bigger. And were expensive. So people resorted to a scheme called batch processing. It was like taking your clothes to the laundromat. You’d take your job in, and leave it in the input bins. The staff people would prerecord it onto these magnetic tapes. The magnetic tapes would be run by the computer. And then, the output would be printed. This cycle would take at best, several hours, or at worst, 24 hours. And it was maddening, because when you’re working on a complicated program, you can make a trivial slip-up - you left out a comma or something - and the program would crash. It was maddening. People are not perfect. You would try very hard to be careful, but you didn’t always make it. You’d design a program. You’d program it. And then you’d have to debug it and get it to work right. A process that could take, literally, a week, weeks, months -

People began to advocate a different tactic, which came to be called time-sharing. Take advantage of the speed of the computer and have people at typewriter-like terminals. In principle, it seemed like a good idea. It certainly seemed feasible. But no manufacturer knew how to do it. And the vendors were not terribly interested, because it was like suggesting to an automobile manufacturer that they go into the airplane business. It just was a new game. A group of us began to create experimental versions of time-sharing, to see if it was feasible. I was lucky enough to be in a position to try to do this at MIT. And we basically created the “Compatible Time Sharing System,” nicknamed CTSS from the initials, that worked on the large mainframes that IBM was producing. First it was going to be just a demo. And then, it kept escalating. Time-sharing caught the attention of a few visionary people, like Licklider, then at BBN, who picked up the mantle. He went to Washington to become part of one of the funding agencies, namely ARPA. ARPA has changed names back and forth from DARPA to ARPA. But it’s always the same thing.

And it was this shift from batch processing to time-sharing that accidentally kickstarted people using computers in a social way…programming together, sending notes to each other, etc.

Robert Fano: Yes, the computer was connected through telephone lines to terminals. We had terminals all over the MIT campus. People could also use CTSS from other locations through the teletype network. CTSS was capable of serving about 20 people at a time without their being aware of one another. But they could also communicate with each other. A whole different view of computers was generated.

Before CTSS, people wrote programs for themselves. The idea of writing programs for somebody else to use was totally alien. With CTSS, programs and data stored could be stored in the common memory segment and they were available to the whole community. And that really took off. At a certain point, I started seeing the whole thing as a system that included the knowledge of the community. It was a completely new view. It was a remarkable event. In retrospect, I wish I had gotten a very smart social psychologist on the premises to look at and interpret what was happening to the community, because it was just unbelievable.

There was a community of people using the computer. They got to know each other through it. You could send an e-mail to somebody through the system. It was a completely new phenomenon.

It seems completely nutty to me that people using computers together — which is probably 100% of what people use computers for today (email, Twitter, Facebook, IM, etc.) — was an accidental byproduct of a system designed to let a lot of people use the same computer separately. Just goes to show, technology and invention works in unexpected ways sometimes…and just as “nature finds a way” in Jurassic Park, “social finds a way” with technology.

This is the first part of a five-part blog post by Errol Morris investigating whether his brother Noel Morris

co-wrote the first working email system at MIT in the mid-1960s. From an MIT colleague of Noel’s, Tom Van Vleck:

In 1965, at the beginning of the year, there was a bunch of stuff going on with the time-sharing system that Noel and I were users of. We were working for the political science department. And the system programmers wrote a programming staff note memo that proposed the creation of a mail command. But people proposed things in programming staff notes that never got implemented. And well, we thought the idea of electronic mail was a great idea. We said, “Where’s electronic mail? That would be so cool.” And they said, “Oh, there’s no time to write that. It’s not important.” And we said, “Well, can we write it?” And we did. And then it became part of the system.

Van Vleck maintains a web page about what he, Noel Morris, and their team were working on at the time. To go along with Morris’ article, the NY Times has an MIT Compatible Time Sharing System emulator that you can use to send email much as you could back in the 60s.

In London during Jane Austen’s lifetime, mail didn’t move at such a snail’s pace.

Austen wrote more than 3,000 letters, many to her sister Cassandra. They corresponded constantly, starting new letters to each other the minute they finished the last one and sharing the minutia of their lives. From reading Austen’s novels, I’d always assumed that people in her era spent a long time waiting for the mail. But the show mentions that during Austen’s life, mail in London and environs was delivered six times a day. Sometimes, a letter sent in the morning was delivered the same evening. Which makes snail mail sound a lot more like email or twitttering.

Update: Two related links: The Twitter-like postcard culture of Edwardian Britain and from 1912, A History of Inland Transport and Communication in England by Edwin A. Pratt. (thx, liz & martin)

Actress Kristin Scott Thomas made an interesting observation the other day while discussing foreign language films:

“People will now go to films with subtitles, you know,” she added. “They’re not afraid of them. It’s one of the upsides of text-messaging and e-mail.” She smiled. “Maybe the only good thing to come of it.”

The abundance of scrolling tickers on CNN, ESPN, and CNBC may be even more of a contributing factor…if in fact people are more willing to see films with subtitles. (via ben and alice)

Inbox Victory: take a photo of yourself and your mail program when you get your inbox down to zero items.

If you Google “email me”, kottke.org is the first result. This may explain all the spam I’ve been getting. (via two separate most-likely-drunken emails last night)

Permanent Vacation, a piece by Cory Arcangel consisting of “two unattended computers send endlessly bouncing out-of-office auto-responses to each other”. (via vitamin briefcase)

Has anyone else noticed that Mail.app and IMAP aren’t perfect playmates in Leopard? The unread counts in my folders don’t update until I click on them (and my inbox unread count never updates), which is suboptimal and time consuming in the extreme.

Merlin Mann on the temptation of declaring email bankruptcy:

Email is such a funny thing. People hand you these single little messages that are no heavier than a river pebble. But it doesn’t take long until you have acquired a pile of pebbles that’s taller than you and heavier than you could ever hope to move, even if you wanted to do it over a few dozen trips. But for the person who took the time to hand you their pebble, it seems outrageous that you can’t handle that one tiny thing. “What ‘pile’? It’s just a fucking pebble!”

This used to be a problem primarily for those, like Merlin, who run high-traffic web sites but now I feel like most people, either because of their jobs or keeping up with friends & family from far away, have email pile problems…we all get more incoming correspondence than we know what to do with.

Email bankruptcy: “choosing to delete, archive, or ignore a very large number of email messages without ever reading them, replying to each with a unique response, or otherwise acting individually on them”.

David Shipley and Will Schwalbe have written an email style guide, an Emily Post for the cubicle set. I can’t abide by the endorsement of excessive exclamation points, but maybe the rest of the book is more useful? Send is available at Amazon.

An HR department looking for someone with internet experience dumped emails from candidates with Hotmail email addresses because “you can’t pretend being an internet expert and use a Hotmail account at the same time”. (via bb)

Tom Hodgkinson has given up on email. “At the weekend I set up one of those auto-reply messages, informing my correspondents that I would no longer be checking my emails, and that instead they might like to call or write, as we used to in the olden days.”

Update: Stanford computer science professor Don Knuth stopped using email more than 15 years ago. (thx, dan)

Apparently, signing off your emails with “Best” is “something close to a brush-off”. I sign most of my emails with “Best”, especially when I don’t know the person particularly well, and I definitely don’t mean it as a brush-off. “Sincerely” is too formal, “Warmest regards” is a lie (you can’t give absolutely everyone your warmest regards), and “xoxo”…I’m not a girl. So “Best” it is…don’t take it the wrong way.

Why the functionality of MsgFiler isn’t automatically built into Mail.app, I don’t know, but I’m definitely coughing up the $8 on this because my life primarily consists of moving email from one folder to another. (via df)

Update: See also Mail Act-On. (thx, brandon)

I’m currently testing out this rule for filtering image spam messages with Mail.app. I’m hoping it works because all of the unfiltered image spam clogging my inbox is slowly killing me. Not sure it’s going to work though…because of kottke.org, I get a lot of email from people who have not previously contacted me. (via matt)

Check out all of the chrome in the new version of Outlook. Good grief. Even the veracity of the emailer’s claim is questionable.

Older posts

Stay Connected